CARACAS — In Venezuela, the United States dollar has been vilified by the socialist regime time and time again for nearly a quarter of a century, and yet, at the end of the day, the Maduro regime can’t get enough of it.

The use of the dollar is the one thing holding what’s left of this country’s economy together as hyperinflation has killed the Venezuelan Bolivar three times and counting.

Today, even though it has never been the country’s legal tender, it is very common to go to any Venezuelan store, no matter how big or small, and see all prices listed in dollars, for products ranging from bubblegum to tech gear.

There was a time not long ago, however, when the draconian currency controls established by the socialist regime made it outright illegal for Venezuelans to possess or use foreign currencies — not just the U.S. dollar, but the euro and any other currency that wasn’t the bolivar.

I almost got arrested in 2017 because of those now semi-repealed currency control laws. This is a brief account of how I got accused of “laundering” the extremely large sum of seventy-five United States dollars and zero cents.

Let’s go back to November 2017, a very difficult era for Venezuelans. The collapse of socialism was at its peak. Food and many basic items continued to be rationed with the aid of fingerprint scanners and ID-card-based restrictions. Most medicine was hard to come by and bread lines were a normal part of my life.

The Venezuelan bolivar was already so worthless that video game currencies — of which, I must remark, there are a seemingly infinite number — were worth much more. As a result, I was able to make more money engaging in gray-area shenanigans in World of Warcraft and odd computer or translation-related gigs than what I could’ve earned through an actual job.

At the time, my mother was fighting liver leiomyosarcoma. Her cancer had progressively worsened because she had only been receiving a partial treatment program because the other half was impossible to find in the country. As the treatment failed, doctors then prescribed a different kind of chemotherapy — one that perhaps could’ve helped her live longer or even make it to remission. We could not find that treatment anywhere and she died four months later.

Like many, I pleaded through social media for help in that unwinnable scenario, and I began receiving help from abroad beginning around August of that year. The thing is, at the time, receiving remittances wasn’t something you could do because of the currency control laws. The solution was in third-party exchanges, online payment processors, cryptocurrencies, and other forms of “out of the box” transactions.

It was Thursday, November 2, 2017, and the plan was simple: arrange a new “exchange” of $100, have the “fixer” receive the money, take his cut, and send the “buyer” the rest. In return, I’d receive a bolivar deposit into my local bank account, money that we intended to use that weekend for food and groceries. It wasn’t my first rodeo at it, and it wasn’t my last. The rest I’d rather disclose once I’m not in this country.

The $100 I “exchanged,” after all the under-the-table fees and commissions, meant that I’d get around $75 worth of bolivars. On that specific day, it meant receiving exactly 3.1 million bolivars.

Venezuelan illustrator Jose Leon shows his artworks painted on devalued Bolivar bills, at his workshop in San Cristobal, Venezuela on February 2, 2018. The bolivar lost so much value as currency that Venezuelans began using them as art canvases in an attempt to make them valuable. (GEORGE CASTELLANOS/AFP via Getty Images)

This is no longer the case today but, back then, those $75 worth of bolivars went a long, long way. They’d get me a decent amount of food for my mother, brother, and myself. Hell, it even allowed me to get both my mom and brother a few treats and things that she had been recommended to eat as part of her fight against cancer, including things she could still taste after chemo had ravaged her sense of taste, such as sweet and sour sauce.

This is where things got complicated.

Because I had never received 3.1 million bolivars in one go, a deposit of that “magnitude” into my bank account locked down the funds and froze the account. As this happened after office hours, there was nothing I could do and no bank phone customer support number to call, so the first order of business was to go to my local branch on Friday to figure out what was wrong and what I could do to get my money.

Initially, I was informed that my funds were frozen because it was such an unusually “high” amount. I was told that a simple letter explaining the origin of the funds would “suffice” to unlock my account. I guess I more or less got called “poor” because I never had had that kind of money in my bank before — the equivalent of $75.

Now, here’s the thing. I could not openly say that the money came from a foreign dollar exchange as that was illegal. So after discussing it with my mother, I had to come up with a plausible lie — not my finest hour, but, when you’re living in a failed state, you do what you have to do for the sake of the people you care about.

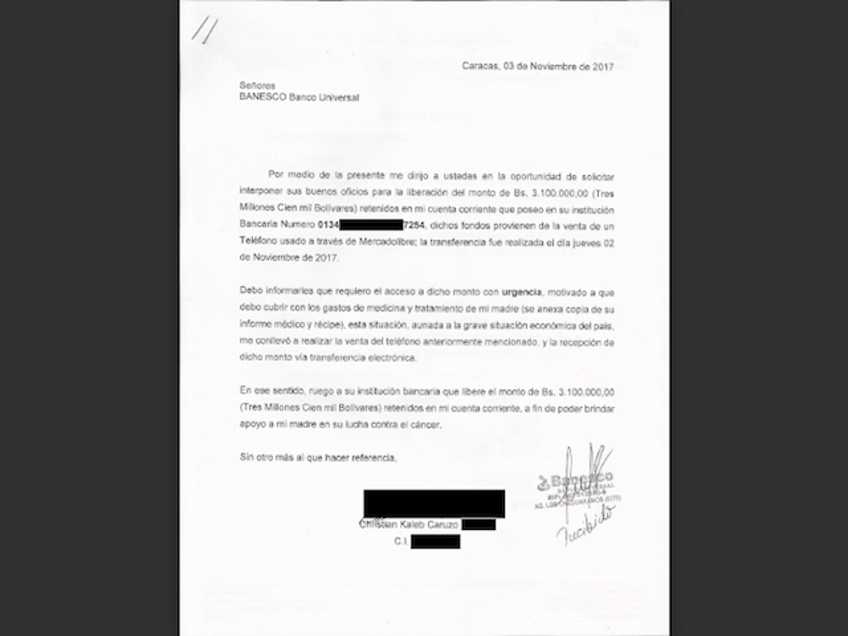

I wrote a letter requesting the money be unfrozen, claiming that the money came from the “sale of a used phone” that took place over Mercadolibre, a website that is our regional equivalent to America’s eBay.

I added in the letter that I really needed the money as soon as possible to buy food and cover some expenses related to my mother’s cancer treatment. I even attached a copy of her up-to-date diagnosis and her latest prescription for pazopanib, a chemotherapy drug that we could never find in this country.

The letter sent to Banesco bank in Caracas, Venezuela, explaining the circumstances of the wire transfer. (Christian K. Caruzo/Breitbart News)

The bank clerk kept one copy of the letter and signed and stamped my copy of it, adding that I should go back on Tuesday to sort this out, as the following Monday was a bank holiday. The weekend went by and, without the money, we couldn’t buy much. That Tuesday was for sure one of the worst days in this ongoing life under socialism.

I went back to the bank, letter in hand, and, after waiting for a couple of hours, I was told to enter the manager’s office.

She cut to the chase and formally accused me — on behalf of the bank — of potentially being engaged in money laundering activities. Yes, I was accused of laundering the equivalent of $75. Some high-roller “money launderer” I allegedly was.

It goes without saying that I panicked and rebutted her accusations. She called the bank’s security department and, through the speakerphone, the person told me that they were going to “verify” if my version was true. Long story short, if the person who sent me the 3.1 million bolivars confirmed my version, I was free to go with my money. If not, they’d call the police and have me arrested on the spot. The bank’s security would stop me from leaving. Even if I tried to make a daring escape I would not have gotten far because, due to rising crime, that bank had no regular doors but instead a set of curved sliding doors that won’t let you in if you’re carrying metal.

My entire fate was left at the hands of a person whose identity I did not know, a complete stranger who could’ve just denied having ever made the transaction.

After a few minutes that seemed like an eternity, the manager received a call, and then she told me that all had been “clarified” and that the person confirmed having made the transaction, so my funds were unfrozen, and I was free to go to “go buy whatever it was that I was going to buy.”

No apology, nothing of the sort.

I never found out who the person who saved me was. All that I know was that he was a local man who “bought” the dollars sent to me in exchange for bolivars, and that the “fixer” for this transaction — and thus my contact in this whole ordeal — was the friend of a friend.

The first thing I did was to call my mother to let her know what happened so she could be relieved. Since it was already past noon and we hadn’t bought food, I went to a nearby McDonald’s that no longer exists and gave my family a “treat” although the place had no ketchup or soft drinks left.

Thankfully, that was the only time I had to face a problem of that kind (knocks on wood). To this day, I still pray to God nightly that this doesn’t ever repeat. The experience left me wary and I became more “surgical” with that kind of stuff.

Some months later, the Maduro regime ended up accusing that bank of the same thing I was accused of, and they seized it for about a year.

Banesco’s offices in Los Chaguaramos, Caracas, Venezuela, the bank where the near-arrest happened. (Christian K. Caruzo/Breitbart News)

This feels like it happened a lifetime ago. As of 2018, it is no longer illegal to hold or trade in foreign currency. Most banks will even allow you to deposit or exchange foreign currency now.

Things are indeed so much different now that, last week, I deposited foreign cash in the very same bank branch where I was nearly arrested six years ago over $75, and nobody batted an eye. The place is almost as I remember it, except that it has been severely downsized due to the ongoing crisis. There’s only one open teller booth, and all customer support offices have been closed down from the premises.

The next time you happen to have $75 in your hands remember that, during the height of socialism’s inevitable collapse, I almost got arrested for that money while the regime’s officials lived a life of luxury.

Christian K. Caruzo is a Venezuelan writer and documents life under socialism. You can follow him on Twitter here.