Manhattan’s Tenement Museum already preserves the history of some immigrants who shaped New York City — from destitute Irish fleeing the great famine to Jewish survivors of the Holocaust — now it is also making room for the lives of African-American migrants.

Beginning next week, visitors to the museum can tour a two-room apartment that is a recreation of one once inhabited by Joseph and Rachel Moore, a Black couple who lived in the area during the US Civil War in the late 19th century.

The Moores squeezed into the unit along with three other boarders.

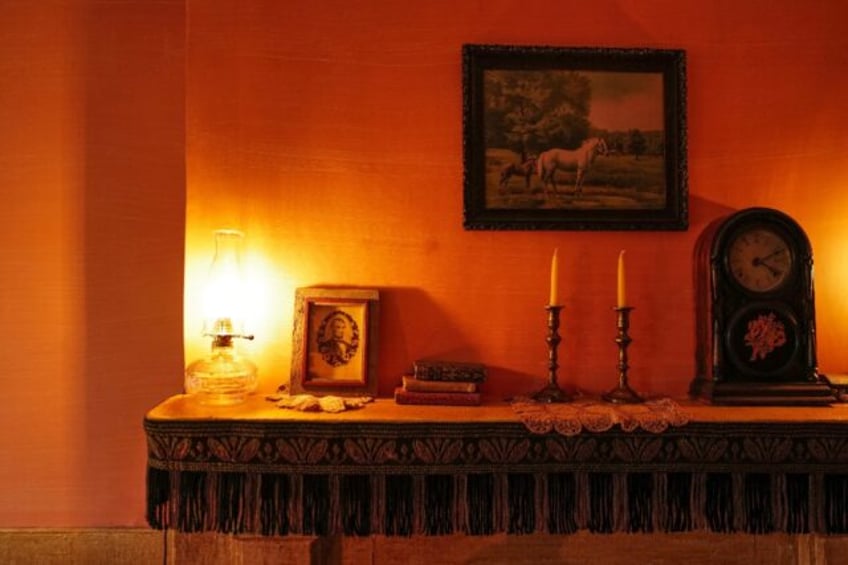

There is no running water. Laundry hangs in the kitchen. On a mantelpiece sits a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, the president who abolished slavery in 1865, as the war between the US north and south drew to an end.

Joseph worked as a waiter or coachman depending on the season, Rachel was a servant and washerwoman for wealthy families.

The couple “moved to the city when they were both pretty young, in their 20s. And they lived in Manhattan through one of the most tumultuous decades of the country’s history, during the Civil War… when Black Americans were gaining some new freedoms for the first time,” explains Kathryn Lloyd, vice president of programs and interpretation at the museum.

Accused of ‘rewriting’ history

The Tenement Museum draws some 200,000 visitors a year who immerse themselves in the history of the millions of migrants who settled in New York in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Many lived in large, old buildings divided into small, often-crowded apartments, which became known as tenements.

The immigrants’ stories echo today in the city, which struggled last year to absorb more than 100,000 migrants from Latin America.

The museum occupies two actual brick tenement buildings at 97 and 103 Orchard Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

The dwellings of some of the former residents have been recreated, including of the Schneiders, German beer saloon owners in the latter 1800s, and the Baldizzis, Italians who survived the Great Depression here.

The Moores actually lived in a similar building in Soho, a district a 20-minute walk away that had a large African-American community.

In the city registry, Joseph Moore appears as “col’d,” for “colored,” signifying that he was Black, right next to another Joseph Moore, also a waiter but Irish, fleeing famine in his native country and whose story is also revealed at the museum.

When its permanent exhibition was expanded to include the Black experience, the museum was accused of “a literal rewriting of history” in an article published in the New York Post, because the Moore family had not lived on Orchard Street.

A broader view of US identity

But after a tour, Vanessa Willoughby, 28, a Harlem resident who works in finance, said she was pleased that the museum had expanded the narrative “to include a Black family in their story telling about working class New Yorkers living in the late 1800s.”

The museum is working to expand the history of immigration beyond that of white Europeans to include Asians and Latin Americans, and now Black American migrants.

For Lloyd, the museum’s vice president, telling the Moore story was crucial to understanding migration within the United States and how the stories add to what “we learn about American identity.”

Rachel Moore, who was “the first generation in her family to be born free” rather than enslaved, arrived in New York in 1847. Joseph arrived 10 years later from neighboring New Jersey, where slavery had not been abolished, unlike New York. Yet the shadow of slavery loomed for him as he risked being kidnapped and taken to the South into enslavement.

In July 1863, the New York City draft riots broke out, which were revolts against enlistment in the army during the Civil War that turned into racist pogroms against New York’s African Americans. The violence claimed at least 120 lives and forced 20 percent of African Americans to leave the city.

The museum lost track of Rachel Moore from 1870 onward, and traced Joseph back to New Jersey, where he returned to live years later. His apartment is described in a newspaper article of the time, which also noted that it contained a portrait of Abraham Lincoln.