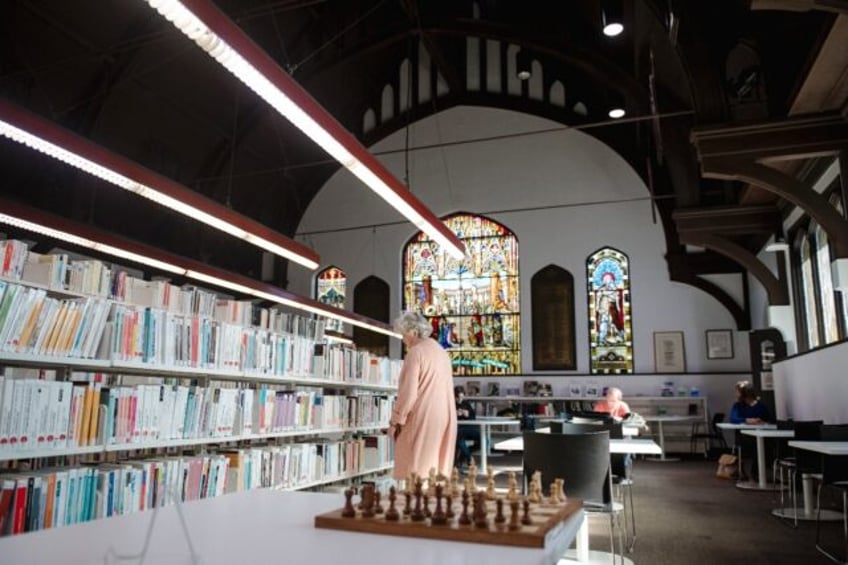

Inside a former Anglican church in central Montreal, crucifixes, prayer benches and candlesticks have been replaced by books and chessboards — part of an effort by developers and community groups to breathe new life into abandoned churches.

“I really like coming here. I like the little church feel, it is conducive for concentrating,” university student Alexia Delestre whispered at the Mordecai-Richler library, which is housed in the old church building.

Across the once highly religious French-speaking province of Quebec, dozens of churches have been transformed into daycare centers, spas, basketball courts, climbing centers and a cheese factory.

“In general, we do not want to destroy churches if we can preserve them because they are beautiful buildings which mark the urban space well,” said Justin Bur, 58, a member of the local historical society Memoire du Mile-End. “They are important landmarks.”

Another 1960s church in Montreal was saved from demolition at the last minute and now houses a residence for the elderly, social housing and a daycare.

Outside, its imposing white concrete structure and its high-perched cross stand out in the urban landscape. Inside, seats and children’s toys fill rooms with high ceilings and large windows.

“It’s really the Rolls-Royce of daycare centers,” boasted Isabelle Juneau, deputy director of La Creche daycare, highlighting the modernist architecture and the brightness of the place.

‘City of 100 steeples’

The repeal in the 1960s — during Quebec’s Quiet Revolution or secularization — of a tax that paid for the maintenance of churches contributed greatly to the abandonment and deterioration of places of worship.

Many have been deserted, including in Montreal, which was nicknamed “the city of 100 steeples” by the writer Mark Twain who once famously said that “you couldn’t throw a brick without breaking a church window.”

Quebec used to be home to around 2,800 churches, but their number has been dwindling, explained Lucie Morisset, an urban heritage researcher. In Montreal alone, there were about 1,000 churches at the beginning of the 20th century, of which only 400 are left today.

“There are no more priests, there are no more religious practices. Society has moved on to something else,” said Morisset.

Over the past two decades, about 100 churches have been redeveloped, according to the Quebec Religious Heritage Council. About ten have been demolished and some forty have transitioned into synagogues, mosques or other types of places of worship.

Costly conversions

Conversions are not always easy, but they have become even more costly lately due to galloping inflation.

Marc-Andre Simard, general manager of the Chic Resto Pop restaurant said it cost several hundred thousand dollars to convert an old church into a community cafeteria. The entire basement was repurposed into a kitchen and the grounds had to be decontaminated after an old heating oil tank leaked.

The restaurant now serves more than 300 meals each day to the neighborhood’s needy while providing kitchen training for the unemployed — amid the original woodwork, multicolored stained glass windows and confessionals.

For Simard, it is “essential that the entire religious heritage is not left to rot” because old churches can still serve as community spaces or residences.