Imagine a street performer standing behind a small table, moving three shells around at lightning speed, concealing a pea beneath one of them. As the audience watches closely, they try to follow the pea’s location, only to realize that no matter how well they track it, they’ve been fooled.

Now, replace that street performer with the Federal Reserve and the U.S. government, the shells with gold, silver, and paper money, and the pea with real value.

This, dear reader, is how the public got tricked into believing in fiat currency—a shell game of epic proportions.

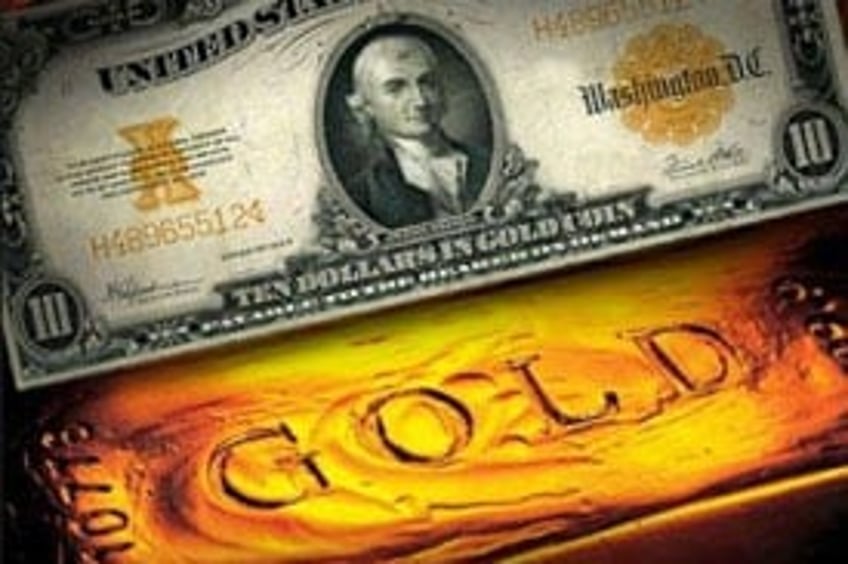

Gold and Silver as Money

Before the game began, money was simple and trustworthy. Gold and silver possessed universally accepted value across time and culture. The U.S. Constitution formally reaffirmed their role as money.

Coins made from these metals weren’t just tokens; they were actual wealth.

But as commerce expanded, many people found carrying gold and silver cumbersome, and paper money—backed by gold and silver—became seen as more practical. This paper was essentially a receipt that could be exchanged for real gold or silver at the bank.

1913: The Federal Reserve Is Born

Here’s where the shells started moving.

In 1913, Congress set up the Federal Reserve Bank cartel. The government and the Fed promised to manage the money supply, and paper money issued by the U.S. Treasury was slowly swapped out for Federal Reserve Notes.

While these notes were still technically backed by gold, it was the first step in separating real money from its paper stand-in. The Federal Reserve now controlled the money supply and could expand or contract it at will, laying the groundwork for the game ahead.

The Sleight of Hand: Commodity-Backed Currency

As the years passed, the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve started playing a clever game. They continued to print more paper than they had gold to back it. But they reassured the public that everything was still fine: "Your dollars are still backed by gold!"

They weren’t technically lying, but fewer people were actually able to redeem their dollars for gold. The shells started moving faster.

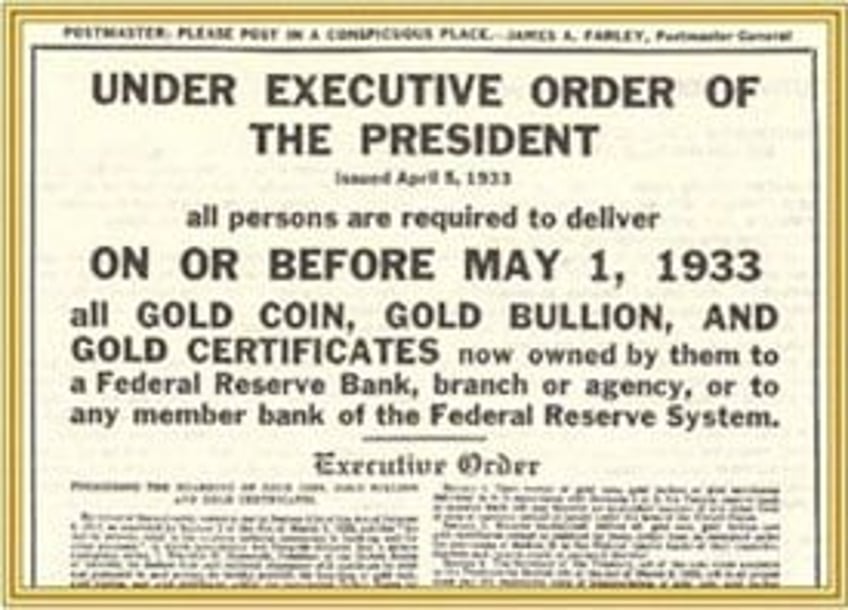

1933: FDR’s Gold Expropriation

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102, which made it illegal for private citizens to own more than five ounces of gold.

Americans were required to turn in their gold coins, bullion, and certificates to the government in exchange for paper dollars at the current exchange rate of $20.67 per ounce. The government, of course, kept the gold.

Suddenly, the public couldn’t even own the very thing that gave their paper dollars value. FDR justified this by saying it was necessary to stabilize the economy during the Great Depression, but it was a pivotal moment in removing real money from the equation.

The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 then raised the price of gold from $20.67 to $35 per ounce, effectively devaluing the dollar by about 40%. The dollar's link to gold was further weakened, allowing for greater government control over monetary policy.

1944: The Bretton Woods Agreement

At the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, the U.S. persuaded central banks across the globe to effectively make the dollar the world’s reserve currency.

Other nations could exchange their currencies for U.S. dollars, which were still formally redeemable for gold. However, only foreign governments—not regular people—could make this exchange.

While this limited gold standard was intended to appear like a strong guarantee of value, the U.S. government kept printing more money than it had gold to back it, especially during the 1960s.

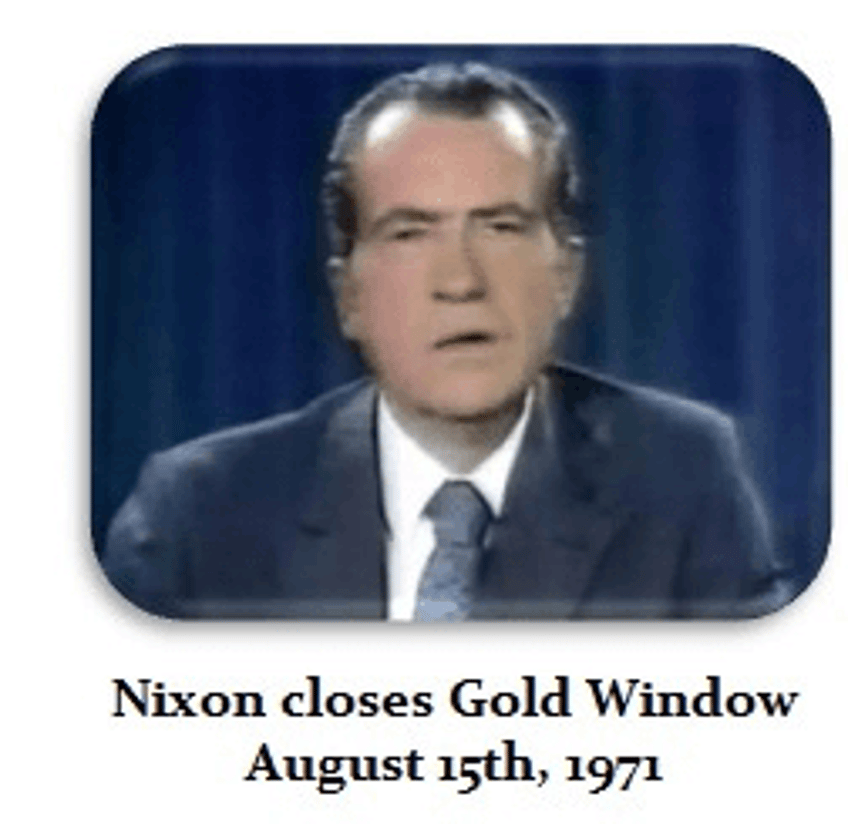

1971: The Nixon Shock

In 1971, the performer’s sleight of hand was revealed. Other nations were turning in their dollars for gold, causing U.S. gold reserves to dwindle.

President Richard Nixon announced that the U.S. would “temporarily” stop allowing foreign governments to exchange their dollars for gold, effectively ending the Bretton Woods system. This event, known as the Nixon Shock, was the moment the pea completely disappeared from the table.

From then on, the U.S. dollar had no tie to gold. It became purely a fiat currency, meaning it was only worth what the government said it was—and what the public and the markets at large believed it was.

The shells kept moving, but there was no pea to find anymore. The game had changed: money was now purely a matter of trust, not tangible value.

1973: Floating Exchange Rates

Two years after Nixon’s move, the world embraced floating exchange rates. Currencies were no longer pegged to a commodity like gold, but their value fluctuated based on market forces and official interventions. The shell game became a global phenomenon, with every major currency unanchored from real value.

The Endless Game: Fiat Currency

Since the 1970s, we’ve been living in the world of fiat money—backed by nothing more than trust in governments and central banks. Central banks, like the Federal Reserve, print money whenever they need to stimulate the economy or bail out failing institutions.

Inflation is a key feature of this shell game. When central banks print more money, the value of each dollar in circulation decreases.

2008 and Beyond: The Modern Shell Game

The shell game hit a new level in 2008 during the financial crisis.

Central banks around the world, including the Federal Reserve, engaged in quantitative easing—a fancy term for creating money out of thin air to buy government bonds and other securities. This massive money-printing effort was meant to stabilize the economy, but it also demonstrated just how disconnected modern money is from any real value.

Today, we live in an era where central banks can create trillions of dollars with the stroke of a keyboard. The shells move at a dizzying speed, and the public keeps watching, hoping the pea is still there somewhere. But is it?

The Trick Revealed: Fiat Money Exposed

What started as real, tangible value—gold and silver—slowly evolved into paper backed by those metals, and then, finally, into fiat currency backed by nothing but trust.

So next time you reach into your wallet and pull out a Federal Reserve note dollar, remember: it’s a piece of paper, part of a shell game that’s been going on for over a century. And like all shell games, it works best when you don’t look too closely for the pea.