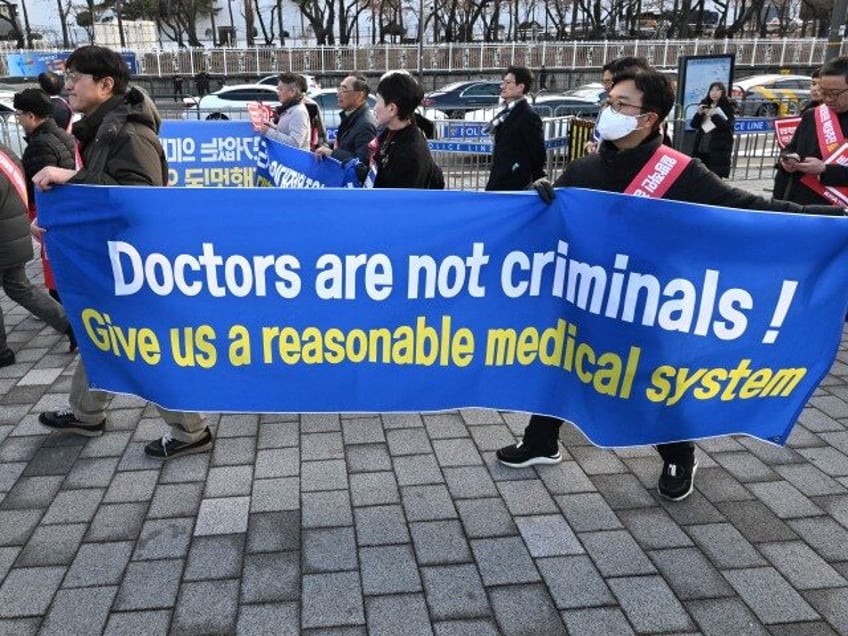

The government of South Korea filed its first legal complaint against striking doctors – specifically, five members of the Korean Medical Association (KMA) – on the grounds that the doctors were engaging in criminal behavior by helping organize and lead the ongoing strike.

Trainee doctors and medical students began walking off the job a week ago in response to President Yoon Suk-yeol announcing a proposal to dramatically increase the number of doctors in the country. Yoon announced Seoul would increase the number of medical students by 2,000 in 2025 and increase quotas with the goal of adding an extra 10,000 medical students by 2035. Currently, South Korea’s medical schools take in 3,000 students a year,

South Korea has long suffered from significant shortages in health workers, particularly doctors, currently employing 2.6 doctors per 1,000 people, one of the smallest doctor-per-person proportions in the developed world. The nation’s small population of doctors tends to choose lucrative fields such as plastic surgery, leaving emergency rooms and pediatric offices understaffed. The declining birth rate and rapidly aging population have also led the government to expect surges in the number of patients in fields addressing medical complications more common in the elderly.

“Increasing the medical school admissions quota by 2,000 is the bare minimum necessary measure to ensure the state can fulfill its constitutional mandate,” President Yoon said in remarks on Thursday, emphasizing the country needs “about 10,000 more doctors to secure an adequate number of doctors in areas with shortages of medical professionals to ensure fair access to health services.”

The doctors have walked out complaining that increasing the number of doctors in the country would mean more competition in the industry and potentially a decline in their salary.

As of Tuesday, the Korean Health Ministry documented the absence of 8,939 intern and resident doctors, about 72.7 percent of the nation’s total, from their jobs; 9,909 have resigned. Nearly 70 percent of medical students, representing about 13,000 people, have taken leaves of absence in solidarity, according to the Korea JoongAng Daily.

The walkout has had a traumatic impact on the South Korean healthcare system. JoongAng reported a 50-percent drop in surgeries performed at hospitals. The government has begun documenting a growing number of delays in emergency room patients being treated. On Friday, an unidentified woman in her 80s died after suffering a medical emergency and being transported to seven different hospitals, all of whom rejected her. The eighth hospital that accepted her reported her dead on arrival. The other seven claimed they did not have enough staff to take her case.

The case remains under investigation, as some officials stated that the woman was also a terminal cancer patient, so they have yet to prove a direct link between the doctor walkout and her death.

Seoul has responded to the medical shortage by empowering nurses, making it legal for them to take on some responsibilities previously exclusive to doctors.

“According to the health ministry, the heads of training hospitals nationwide will be able redefine the scope of nurses’ duties through internal consultation starting Tuesday, depending on each nurse’s level of skill and qualifications,” Korea’s KBS network explained.

The move has put outsized pressure on nurses, however, who are now expected to work longer hours doing jobs they do not have experience in.

“Because there are no doctors to accompany patients in case of emergency during patient transportation, nurses were told to take over the task while the working hours which used to be until 7 p.m. have been extended to 10 p.m.,” an anonymous nurse told the Korea Herald. “PAs have been prescribing medication using the doctors’ IDs, knowing that they wouldn’t be protected if there were problems with the patient’s safety. However, because there is a shortage of doctors in the field, such incidents have occurred frequently with no choice.”

The first five criminal complaints related to the walkout are reportedly against KMA leaders facing charges of “the violation of the medical law and obstruction of justice,” the Korean news agency Yonhap reported on Tuesday. The doctors, whose names have not appeared in public reports, were reportedly helping other doctors organize their strikes by offering legal help and organizing advice.

“We will continue to respond under the law and the principle for illegal collective action,” Health Minister Cho Kyoo-hong asserted on Tuesday, adding that all other doctors had until Thursday to return to work if they wished to avoid criminal charges.

“Starting March, suspending licenses and initiating legal proceedings will be unavoidable for those who do not return,” Cho warned.

Yonhap noted that the South Korean government has the power to revoke medical licenses as a direct result of criminal convictions related to walking off the job.

Yoon backed up the Health Ministry in comments on Tuesday sternly condemning the medical field.

“It is impossible to justify collective action that takes people’s health hostage and threatens their lives and safety,” he said from South Korea’s presidential office, the Blue House. Yoon asserted that increasing the number of doctors in the country “cannot be the subject of negotiation or compromise.”