Two years of fighting after Russia's brutal 2022 invasion of Ukraine has the world asking what peace between the two nations can possibly look like and what is the possible path to end a war that has left a nation shredded and hundreds of thousands dead.

Calling the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine a violation of the UN Charter and international law, UN Secretary-General António Guterres on Friday said the war has created "an open wound at the heart of Europe" that only diplomacy could fix. "It is high time for peace—a just peace, based on the UN Charter, international law, and General Assembly resolutions," declared Guterres.

The Secretary-General condemned the invasion as a "dangerous precedent" set by Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has claimed eastern regions of Ukraine rightfully belong to Russia and justified the war as necessary to block the ongoing expansion of NATO that betrayed earlier promises by the military alliance.

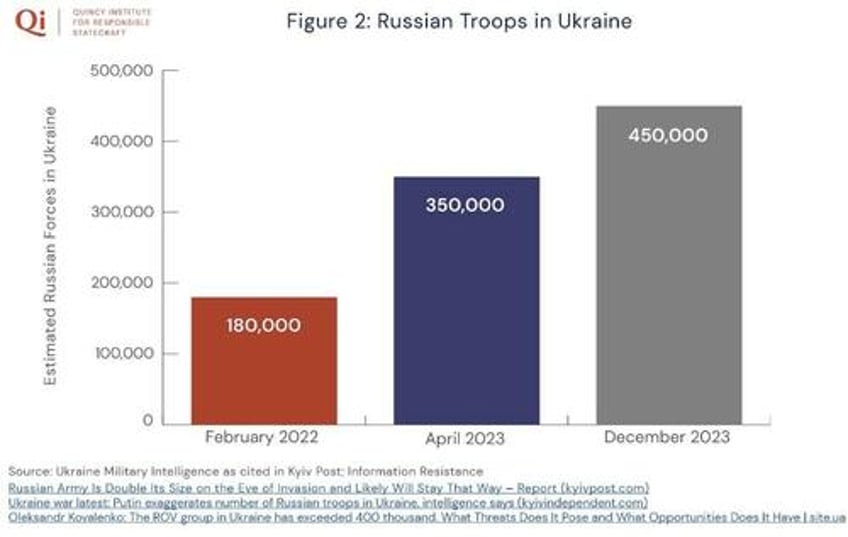

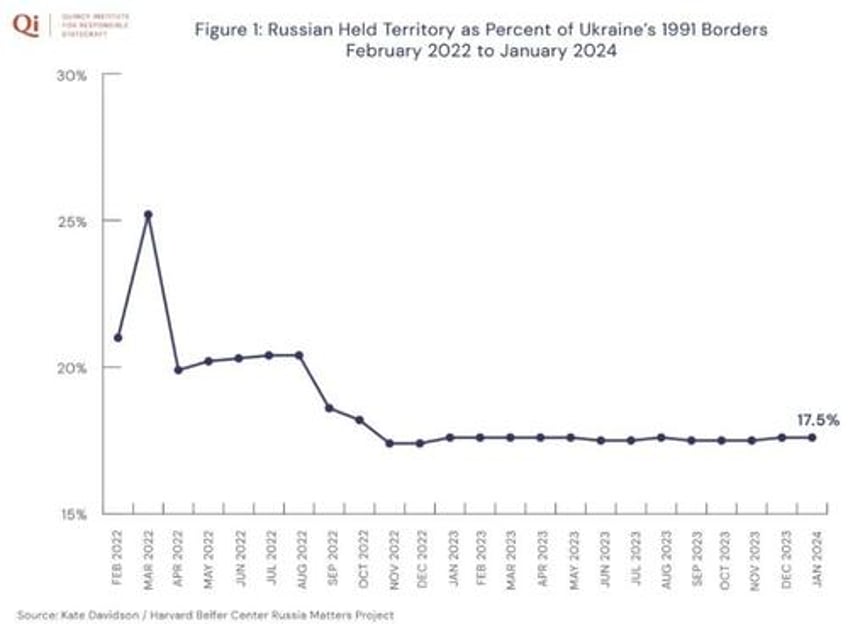

As the war enters its third year, foreign policy experts argue that the current standstill—in which Russia has realized it cannot possibly take the whole country by force and Ukraine is unlikely to have the might to push the invading army back over the border—proves there is no military solution.

In a brief published to mark the two-year anniversary of the war's start, Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecrafts analysts Anatol Lieven and George Beebe argue that the people of Ukraine have much more to win than lose by seeking a diplomatic solution.

"Conventional wisdom holds that a negotiated end to the Ukraine war is neither possible nor desirable," Lieven and Beebe's paper states. "This belief is false."

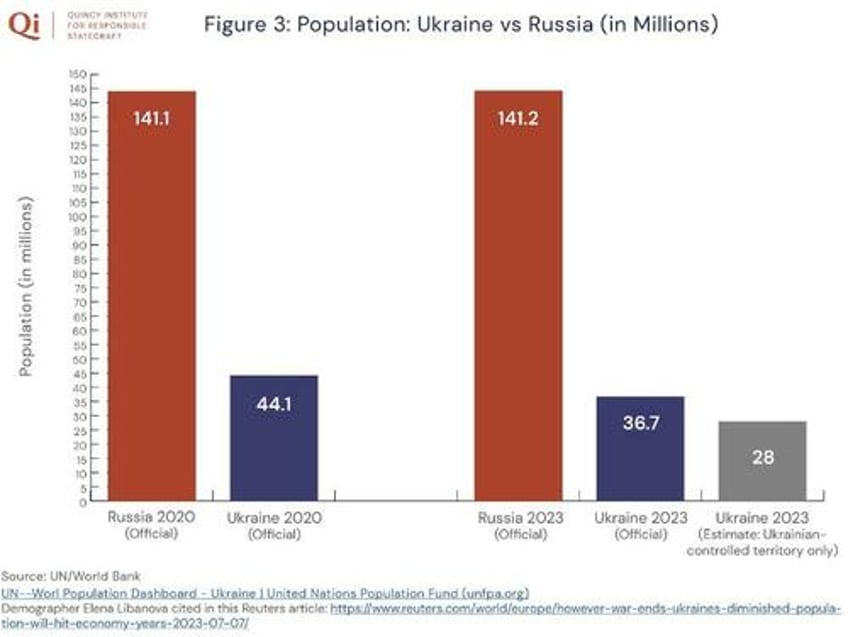

The pair war that resistance to diplomacy is "also extremely dangerous for Ukraine"s future because the bloody war—in which over 10,000 Ukrainian civilians have been killed and more than 5 million displaced—"is not trending toward a stable stalemate, but toward Ukraine’s eventual collapse."

The New York Times reports Sunday that while Ukrainians are "weary" of the bloody war that has taken so much from them, "but ever determined to repel the invaders."

The Times interviewed Dr. Maryna Prokopenko, a surgeon at Kharkiv Regional Hospital, who said the battered bodies and suffering she sees inform her desire for "this war to end," but said ceding territory to the Russians was unacceptable.

But with the Ukrainian military "outgunned and outnumbered against a more powerful opponent," as the Associated Press reports—and additional foreign military assistance stalled in the U.S. Congress and by other allies in Europe due to domestic concerns about prolonging support for a war with no end in sight—the idea of a negotiated settlement has deep appeal for many.

"As things stand, neither side has won. Neither side has lost. Neither side is anywhere near giving up. And both sides have pretty much exhausted the manpower and equipment that they started the war with," claimed Richard Barrons, a retired British general and current co-chair for Universal Defence & Security Solutions, a military consultancy firm.

While militarists argue the U.S. and other NATO countries must double-down on their support for Ukraine to combat Russian aggression, critics of endless war say it is Ukranian civilians paying the biggest price over the refusal to forge a negotiated settlement leading to a peace agreement to end the war.

"To resolve the ongoing crisis, diplomatic engagement through negotiations and mediation needs to be given more consideration," says Omotola Adeyoju Ilesanmi, a senior research fellow at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs, in a memo this week. "Further, it ought to take precedence over other inefficient measures, such as using military force to accomplish political goals."

The U.S.-based peace group CodePink issued a statement Friday similarly arguing that two years of war have proved that there is no military solution and that another $61 billion in U.S. military assistance—mostly in the form of more bombs, missiles, and other armaments—would not do more than the $113 billion already spent overall on assistance.

"Prolonging the war in Ukraine will not stabilize the region nor bring peace to Ukrainians; only peace talks and diplomacy can do that," the group said. "Stop the weapons. Start the talks."

Contrary to conventional wisdom, Lieven and Beebe argue in their assessment that the United States and other powerful allies to Ukraine have more leverage now to bring Russia to the negotiating table even as the Ukraine army appears weaker than at previous intervals in the war. As they write:

Russia cannot conquer, let alone govern, the majority of Ukraine, nor can Russia secure itself against the ongoing threats of Ukrainian sabotage or potential NATO strikes absent a costly permanent military buildup that would undermine its civilian economy. Reducing the deep dependence on China created by the invasion will also sooner or later require Russia to seek some form of détente with the West.

As a result, the United States has significant leverage for bringing Russia to the table and forging verifiable agreements to end the fighting. But this leverage will diminish over time. The United States should therefore quickly challenge Putin to make good on his insistence that Russia is willing to negotiate by publicly supporting calls from China, Brazil, and other key Global South actors for talks to end the war.

In a recent column promoting a new kind of engagement by the U.S. government, Lauren Evans, program assistant for peacebuilding at the Friends Committee on National Legislation (FCNL), mourned the "devastating conflict and catastrophic harm to civilians" across Ukraine over the last two years and said the "situation cannot improve un the war stops."

"While the U.S. cannot and should not dictate terms of peace," wrote Evans, "it can be a better champion of a diplomatic resolution and help envision a new security paradigm in Europe based on the principles of shared security, not the threat of force."

Those pushing for the diplomatic path acknowledge it will be a hard path, but say the alternative of war cannot be the permanent choice. "Even if the United States embarks seriously on an effort to create a path to negotiations, the process of compromise will not be easy or simple," Lieven and Beebe conclude. "But the alternatives—for Ukraine and the world—will be far worse."