The 3 Planks Of The Bernanke Manifesto (Part 1)

"How much extra pop could this policy have delivered?"

- Ben Bernanke discussing moving from QE to NIRP in 2008

Submitted by GoldFix; Authored by Arcadia Economics

During my research this week I happened to stumble across something I had never seen before, that not only was shocking, but also gives you an idea of what the Fed has been thinking as it tries to undo the credit it has added into the markets since 2008.

Picture:GoldFix

I happened to be searching for what Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke actually said about ‘helicopter money’ (for reasons you’ll see at the end of today’s update), and found out that apparently he was writing a column for the Brookings Institute a few years ago, where he had a 3-part series in 2018 titled, ‘What tools does the Fed have left.’

I thought I would be able to cover all of these in just one column, until I actually started reading. Because some of the comments are so wild, that each one of his essays deserves its own attention.

Just to give you an idea of what we’re looking at here, these are the titles of the 3 pieces in the Bernanke Manifesto trilogy:

- What tools does the Fed have left? Part 1: Negative interest rates

- What tools does the Fed have left? Part 2: Targeting longer-term interest rates

- What tools does the Fed have left? Part 3: Helicopter money

Part 2 could likely well have also been called ‘Yield Curve Control’ or ‘Financial Repression.’ Although that aside, even reading the titles of these articles gives you a good idea of what the Fed has been planning as its exit strategy for at least 6 years now (and likely more). There’s quite a bit to cover, so let’s get right to it.

First, is a quote from the beginning of the article.

“We can’t rule out the possibility, though, that at some point in the next few years our economy will slow.”

Despite the boom-bust cycle of the past 25 years in particular, it’s interesting the way he phrases the ‘possibility’ of a recession ‘at some point.’

As if the Fed’s stewardship of monetary policy has been that exact and precise that they have it so dialed in now, that even recessions are viewed as some sort of mystical unicorn.

Since this piece was written in March of 2018, it doesn’t address how Powell had to start lowering rates again just over a year later in August of 2019.

Or the COVID crisis.

Or Jerome Powell’s claim in July of 2021 that inflation would be transitory (despite the fact that year-over-year core CPI had just crossed over 3%, and hasn’t come back down below that level since).

Nonetheless, in the ‘unexpected’ scenario in which there’s ever a recession again, how does Bernanke expect the Fed would react?

“Given where we are today, how would the Fed respond to a hypothetical economic slowdown? Presumably the central bank’s first response, after dropping any plans to raise rates further, would be to cut short-term interest rates, perhaps to zero.”

Since Jerome Powell has already cut short-term rates by 75 basis points over the Fed’s last 2 meetings, despite saying at the September meeting that he doesn’t ‘see anything that suggests the likelihood of a downturn is elevated,’ it’s probably not unreasonable to assume that Bernanke is right that if Powell did see something like that, that rates could get back down to 0% pretty quickly.

Bernanke then mentions:

“That said, there are signs that monetary policy in the United States and other industrial countries is reaching its limits.”

Interesting that he does acknowledge that there are limits to the current Keynesian experiment.

Yet Powell’s latest actions suggest that he either doesn’t see those limits, or he doesn’t care about them.

But Bernanke continues by saying:

“With the fed funds rate near zero, the FOMC could next turn to forward guidance, that is, to communicating to markets and the public about the Fed’s policy plans. If the Fed can convince market participants that short-term rates will stay low for some time, it can “talk down” longer-term rates, such as mortgage rates, which are typically more important to consumers, businesses, and investors (when central bankers get together over a ginger ale, they like to call these efforts “open-mouth operations.”)

Yes, he did actually include that part calling the FOMC ‘open-mouth operations.’

He continues:

The evidence suggests that forward guidance can be quite powerful, and if the amount of extra policy support needed is not too great, rate cuts plus guidance might be all that is needed.”

So just tell investors what they should think, and that will fix the situation?

Is that what Powell was doing when he told the world that the economy’s fine while simultaneously cutting rates by 50 basis points in September?

“But what if not? The Fed could resume quantitative easing (QE), that is, purchases of assets (typically longer-term assets) for the Fed’s portfolio, financed by the creation of reserves in the banking system. Like forward guidance, the goal of QE is to reduce longer-term interest rates to encourage borrowing and spending.”

So if cutting rates to 0% doesn’t do it, just start up the QE again too?

“But the FOMC might be reluctant to turn to it again.

It’s hard to calibrate, and communicating about it is difficult (as we learned in 2013 when Fed talk about ending QE led to a “taper tantrum” in financial markets). It’s also possible that a new round might be less helpful than before. For these reasons, before undertaking new QE, the Fed might want to consider other options.Negative interest rates are one possibility.”

So in the odd case that direct monetization of debt still doesn’t fool people into additional asset speculation, the next step is to just take the value of investors’ capital right out of the currency with negative interest rates.

“Ultimately, the efforts of banks and other investors to avoid negative returns on the shortest-term assets should lead to declines in a broad range of longer-term interest rates, such as mortgage rates and the yields on corporate bonds.”

He doesn’t mention what happens when rates rise. Which commercial real estate investors and banks holding treasuries purchased when rates were at zero found out, in particular in the first quarter of 2023.

“The idea of negative interest rates strikes many people as odd.”

Well, at least there’s finally something we agree on.

“Economists are less put off by it, perhaps because they are used to dealing with “real” (or inflation-adjusted) interest rates, which are often negative.”

Translation - the economists at the Fed aren’t fazed by savers and capital accumulators getting a negative interest rate.

Why is that?

Because in reality, the Fed has known that ‘real’ interest rates have been negative all along!

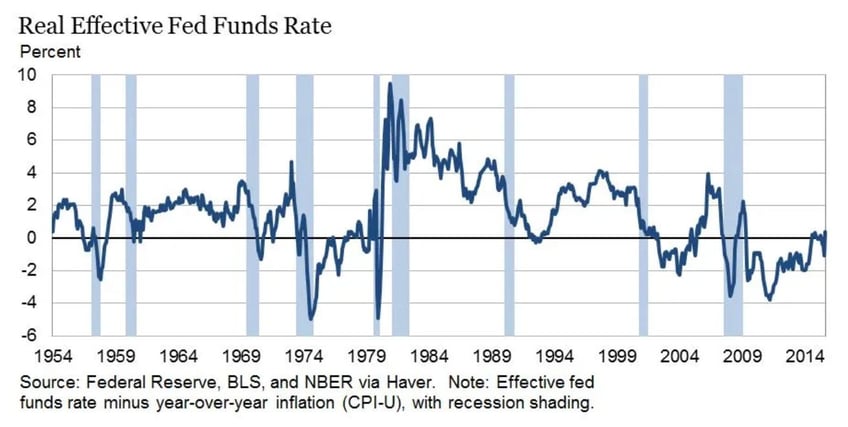

“Since the real interest rate is the sticker-price (nominal) interest rate minus inflation, it’s negative whenever inflation exceeds the nominal rate. Figure 1 shows the real fed funds rate from 1954 to the present, with gray bars marking recessions. As you can see, the real fed funds rate has been negative fairly often, including most of the period since 2009.”

So real rates have been negative fairly often, including most of the time since Bernanke started QE. And now that he thinks QE might eventually stop working, he’s saying that if that does indeed happen, the solution is to just get nominal rates into negative territory too.

“For most of the period reflected in Figure 1, the Fed had no need to implement a negative interest rate in order to ease policy: Until 2008, the nominal fed funds rate was always well above zero, so that ordinary interest rate cuts remained feasible when needed.

Since late 2008, however, the fed funds rate has been barely above zero much of the time, so that achieving further reductions in the real funds rate would have required taking the nominal rate negative.”

This statement makes it almost seem like a miracle that we haven’t had negative nominal rates already.

“In principle at least, how much extra pop could this policy have delivered?”

A little disturbing to hear the man who was once in control of the world’s reserve currency making decisions based on ‘how much extra pop’ they can achieve.

Does that negative interest rate come with some smack too?

Bernanke also had an interesting comment on how he expected the markets would react if the Fed ever did implement such a policy.

“If during this period the Fed had decided (and been able) to lower the short-term nominal interest rate to, say, -0.5 percent, then it presumably could have achieved a real fed funds rate half a percentage point lower as well. For example, instead of being -3.8 percent in September 2011, the real fed funds rate might have been around -4.3 percent, with commensurate declines in other interest rates.”

Although as we’ve learned in the past 2 months, lowering the Fed funds rate doesn’t always bring long-term yields lower as part of that equation.

Sadly, at least Bernanke’s first article doesn’t seem to offer any commentary about what to do when rates blow out like that following Fed cuts.

Although he did introduce the possibility that even the negative interest rate policy might still not produce the intended effect.

“As you can see, the amount of extra stimulus generated by this further reduction in rates would not have been negligible by any means (roughly, it would have corresponded to two extra quarter-point rate cuts in more normal times), but neither would it likely have been a game-changer.

In August 2010, Federal Reserve staff prepared a memo for the FOMC evaluating the likely effects of cutting the interest rate paid on bank reserves to zero or below. That memo, recently released by the Fed, was lukewarm about negative interest rates for mostly practical reasons.”

Once again however, he explains that the effectiveness of the policy is based on what the Fed can get market participants to believe.

“A general conundrum is that central banks need market participants to believe negative rates will be in place for a long time for there to be much effect on economically important long-term rates; but if market participants believe that, they’ll have even more incentive to buy vault space and pay the other costs involved in hoarding cash.”

Yet despite adhering to a strategy that requires investors to believe what the Fed wants them to believe, as opposed to what’s actually happening, Bernanke thinks all of the push-back is unwarranted.

“The anxiety about negative interest rates seen recently in the media and in markets seems to me to be overdone. Logically, when short-term rates have been cut to zero, modestly negative rates seem a natural continuation.”

Once again, at least he does acknowledge that we were living under negative real rates for much of his tenure.

However he doesn’t mention whether it’s wise to actually believe in the Fed’s forward guidance, which includes infamous statements such as his own ‘subprime is contained,’ before we heard Powell years later explain how the inflation would be transitory.

“On the other hand, the potential benefits of negative rates are limited, because rates that are too negative would trigger hoarding of currency.”

Although at least he does acknowledge that even taking rates into negative territory has a limited ability to achieve the effect that the Fed desires.

“We can imagine a hypothetical future situation in which the Fed has cut the fed funds rate to zero and used forward guidance to try to talk down longer-term interest rates. Suppose some additional accommodation is desired, but not enough to justify a new round of quantitative easing, with all its difficulties of calibration and communication.

In that scenario, a policy of modestly negative interest rates might be a reasonable compromise between no action and rolling out the big QE gun.”

Sadly, the ability to post a comment on this article has been closed off. As it would have been fun to hear more about the ‘difficulties of calibration,’ which makes it sound like the QE programs are more trial and error than the precise calculated operation that the Fed leads market participants to believe it is.

But that’s part 1 of Bernanke’s trilogy. And if you think some of the statements in this one were wild, just wait until you hear what he had to say in part 2 on targeting long-term interest rates, which we’ll pick up next week.

Although to leave you with something for some entertainment over the weekend, here’s a tribute to Ben, that after 3 years of development, we’ve finally made public.

Hopefully that brings a smile to your face, and helps you to giggle rather than cry about the insanity of what we’re living through.

Sincerely,

Chris Marcus