Micro-schools offer students a small community as well as flexible schedules and assignments

Education leader details why 'micro-school' interest is surging among parents

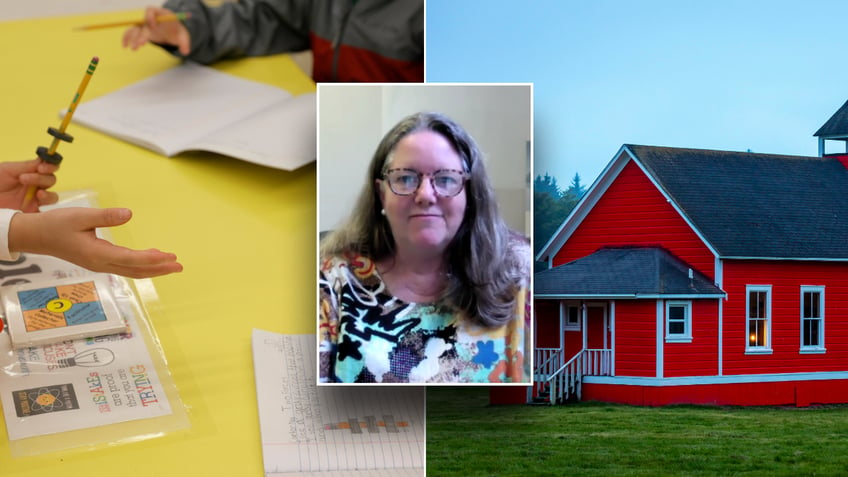

Micro-school founder Siri Fiske says the alternative education institution offers more flexibility for parents and students.

Dwindling confidence in public education across the United States has pushed some parents to enroll their children in "micro-schools," an alternative learning center that gained steam following the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the nonprofit EdChoice, school closures have pushed some families to question the approach of traditional educational environments. Micro-schools, which initially bloomed in the early 2000s, are often one-room schoolhouses that place various age groups together for small classes.

Academic Influence Senior Vice President Dr. James A. Barham told Fox News Digital that class sizes often hold only 10 to 20 kids, and the student-teacher ratio is between 5-to-1 and 10-to-1, compared to 20-to-1 in traditional schools.

"A lot of micro-schools these days focus on project-based and experiential learning, too," Barham said. "The kids I've met are really engaged because they're not just sitting at desks — they're out in the community, collaborating on hands-on projects and drawing real-world connections. It reminds me of my own school days when Friday field trips got me excited about learning."

Microschool founder Siri Fiske told Fox News Digital the COVID-19 pandemic and an embrace of alternative education programs has led to a renewed interest in micro-schools. (Michael Loccisano/Visions of America/Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Micro-schools, also known as learning pods, offer students schedules and curriculum tailored to their individual needs. These schools are often viewed as a middle ground between traditional schooling and homeschooling.

Barham, who has worked closely with public and private schools, said micro-schools' choice and flexibility are a big reason for their growing popularity. Families are increasingly interested in options that go beyond standardized testing and the one-size-fits-all model.

While many micro-schools are parent-led, some are affiliated with a micro-school network. Some are tuition-free, while others are fee-based, like a private school.

Barham noted that micro-schools tend to be more affordable than private schools, thanks to their small size.

"With all the challenges that came from the pandemic, it's no surprise interest in micro-schools has accelerated," he said. "Their close-knit approach proved very conducive to virtual learning and addressing students' social-emotional needs. I expect their student-centered philosophy will continue drawing more families who want education optimized for every child."

Following her son's daunting experience at a traditional Texas inner-city school, Black Orchids PR CEO Chenadra Washington searched for other options. Her child now attends a micro-school three days a week and is homeschooled on Mondays and Fridays.

THOUSANDS OF SCHOOLS RISK CLOSURE DUE TO 'MASSIVE' ENROLLMENT LOSS: NEW REPORT

Students line up to enter their respective classrooms. (Craig Hudson)

"This hybrid approach allows me to stay closely connected to his learning journey, ensuring his education aligns with my values and his unique needs. Most importantly, this option has given me more peace, knowing that I am closely involved in his education and well-being," Washington told Fox News Digital.

She said micro-schools' flexible, personalized nature helps cater to individual learning styles. Furthermore, the model provides a balance for parents like her who seek greater involvement in their child's educational journey.

Americans' souring on public schools is likely a significant factor in parents' turning to micro-schools. A 2023 Gallup poll found that only 26% of Americans surveyed indicated a "great deal" or "fair amount" of confidence in public education institutions.

Public education, policing, tech companies and big business are all at or tied with record lows in terms of public confidence. However, confidence in small businesses is high.

Siri Fiske, a leader in the global micro-school movement, said many of these educational programs offer "mastery-based learning," a far cry from the "factory model," where students of a single age group march through the same curriculum together.

"We group the kids according to what they actually need to know, as opposed to all the 8-year-olds who are going to be in a group together," she told Fox News Digital.

For example, a 9-year-old writing at a second-grade level but reading at a fifth-grade level would be placed in two different classes with mixed ages based on their proficiency.

WHAT PARENTS AND THEIR CHILDREN REALLY NEED IN EDUCATION

Interior of a traditional school classroom with wooden desks and chairs. (iStock)

Fiske said small schools have existed since the early days of the United States, but micro-schools take a quite different approach.

Fiske, who founded America's first self-proclaimed micro-school, said these programs also tailor individual assignments to students by leveraging content on the Internet. For example, if one girl loves corgi dogs, her writing assignments may use that as the basis of the prompt for that student only.

The idea has even made its way to the tech world. In 2016, Fiske visited the Astra Nova School, an online school founded by Elon Musk on the SpaceX campus. Upon her visit, she learned that the program had very similar models, focused on interdisciplinary and problem-based learning, to those she used at her school in Washington, D.C.

Outside the pandemic, Fiske said a general dissatisfaction with traditional education, stemming from the lack of adequate teachers and the treatment of teaching as a profession, has pushed more parents to find new avenues for their child's learning.

An image of students working in class while a teacher speaks. (iStock)

She also suggested that the advent of being able to look up information quickly on the Internet has parents, especially young parents, questioning whether memorizing and reciting information is the best approach. Politics, Fiske said, has also impacted how parents respond to education.

"We had a family come yesterday who had pulled their kid out of the public schools nearby in Maryland because the curriculum they were using to teach what constitutes a family was not aligned with their values," she said.

These factors have led communities to band together and bring parents deeper into the equation.

"I think parents are really hesitant as a group of people to take a risk with their children. Like, they don't want their kids to miss out on something. And so, I think sort of culturally, it's become okay to do some sort of alternative education. And that has opened a lot of new doors," Fiske said.

Nikolas Lanum is an associate editor for Fox News Digital.