The United Nations Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, Obokata Tomoya, asked the communist regime of Cuba to respond to evidence that it was selling its citizens to nations such as Spain, Italy, Ghana, and Qatar for labor exploitation in a letter published Tuesday by the human rights organization Prisoners Defenders.

Prisoners Defenders is a Europe-based NGO that has focused on documenting human rights abuses in Cuba. It filed a complaint with the United Nations against Cuba in 2019 accusing the Castro regime, and offering copious evidence, of selling health workers, athletes, artists, and laborers as slaves to a long list of countries around the world. Cuba’s medical slavery – in which it forces doctors, often under duress and with minimal information on where they are going – is one of the communist regime’s most lucrative industries, netting as much as $11 billion a year in profit for the impoverished nation’s 65-year-old government.

Some 100 Cuban doctors follow proceedings during their induction programme at the Kenya School of Government, on June 11, 2018, in Nairobi. (SIMON MAINA/AFP/Getty Images)

Cuban health workers trapped in the industry often have the vast majority of their salaries confiscated, lose their right to free movement and travel, cannot meet with their families or develop friendships or romantic relationships with locals, and are forced to work in dangerous locales. Two Cuban doctors forced to work in Kenya who were abducted by the Sunni jihadist terror group al-Shabaab, Landy Rodríguez Hernández and Assel Herrera Correa, remain missing at press time, nearly five years after their disappearance in 2019.

The international legal definition of slavery, as presented in the 1926 Slavery Convention, describes it as “the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised.” The United Nations considers modern slavery as a broad category of violations including “forced labor” and “human trafficking.” The U.N. letter addressed to Cuba refers to potential violations of “forced labor” restrictions.

Cuban doctors form up during a farewell ceremony as they get ready to leave for Italy to help with the new coronavirus pandemic, in Havana, Cuba, Sunday, April 12, 2020. (AP Photo/Ismael Francisco)

Prisoners Defenders has galvanized the Special Rapporteur on Slavery regarding Cuba’s slave trade in addition to several other United Nations offices, including that of the Special Rapporteur on Trafficking in Persons, the Committee on the Rights of the Child, and the High Commissioner for Human Rights. The U.N. Human Rights Council is dominated by repressive dictatorships, however, and has made no effort to address the issue or the many other human rights violations the Castro regime routinely engages in. Cuba is currently a member of the U.N. Human Rights Council.

Obokata’s letter, sent to the presidency of Cuba in November and published by Prisoners Defenders on Tuesday, indicates that the U.N. official considers the accusations and evidence convincing enough to require a response from the country in question. Obokata gave the Cuban regime 60 days to respond, which have passed since the letter was sent with no public comment or response from Cuba, Qatar, Italy, Spain, or any other nation implicated.

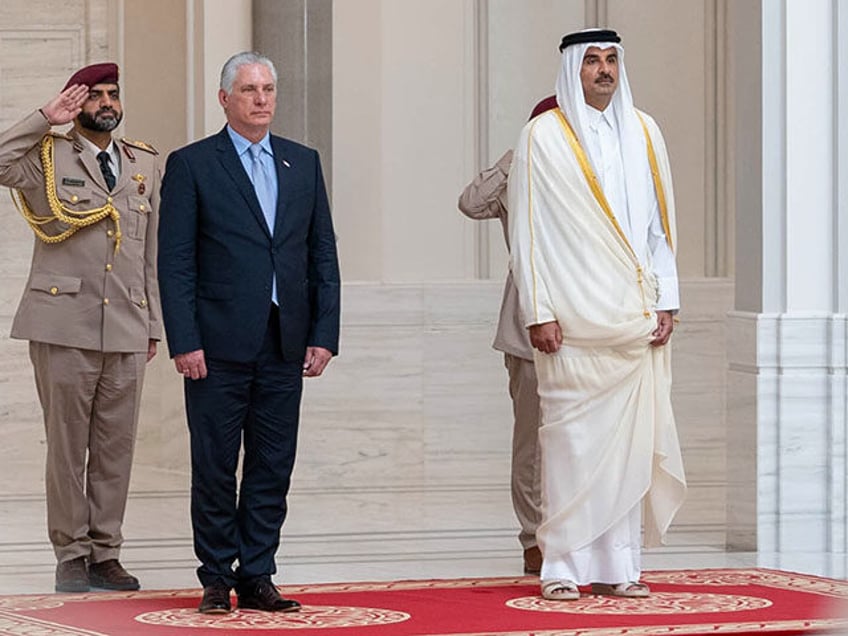

Qatar – a government with its own rich recent history of engaging in slavery – stands accused of being a prominent collaborator with Havana in enslaving Cubans.

“In Qatar, Cuban medical personnel – doctors, nurses, and technicians associated with healthcare – would not receive labor contracts and … only 10 percent [of salaries] would be given to the medical personnel,” Obokata wrote, listing the allegation against Cuba. “As a consequence, Cuban health workers would not receive a salary that would allow them a dignified life in Qatar.”

Cuban slaves in Qatar, most of them believed to be health workers, work about 64 hours a week, Obokata wrote.

RELATED VIDEO — White House: China-Cuba Spy Base Report Not True, but We Won’t Say How or Deny Plans for Base Exist:

In addition to not being allowed to see their labor contracts and losing 90 percent of their wages, Cuban workers in Qatar immediately have their passports confiscated at the Doha airport, Obokata wrote, and “many times do not have any precise information on their destination or place of work” before they arrive.

The workers also reportedly lose their rights to a personal life – in Qatar and other nations collaborating with the Castro regime. The workers must “inform an immediate superior about a romantic relationship, with a Cuban or a foreigner,” and similarly request permission from a superior to get married or receive a family or friend visit. They cannot choose what to do or where to go during the little vacation time allotted and do not have any freedom to hold views, political or otherwise, the Castro regime deems a violation of its nebulous “moral” code.

“Other allegations received refer to permanent vigilance by Cuban officials and other workers; the imposition of personal and political questions on professionals,” Obokata narrated, “not being allowed to drive, leave the house after certain hours; not being allowed to receive family or friend visits or to sleep outside the assigned space without prior authorization.”

In addition to Qatar, the letter accused Spain of similarly exploiting “athletes, artists, musicians, dancers, and other Cuban professionals … through Cuban corporations that retain a great part of their salaries.” Italy, Saudi Arabia, Ghana, and Seychelles also appeared on the list of accused collaborators with the Castro regime.

The letter also accused Cuba of forcing Cuban women enslaved abroad to give birth in Cuba, prohibiting Cuban nationals from seeking to move out of the country, and exposing the slave workers to “sexual violence” and “physical violence” in their host countries. It also noted the evidence that many of the workers “are not voluntarily participating” in foreign communist “missions,” either coerced directly by the Castro regime or by the pervasive state of universal – with the exception of senior Communist Party officials – poverty the Castro regime imposes on its citizens.

Obokata wrote that the letter was intended to reinforce his “concern about the alleged abuses of fundamental rights,” granting that he “fully recognize[d] the value of Cuban cooperation and the important contributions that have been achieved regarding medical attention in many countries around the world.”

“Although the letter has been made public, no responses have been received from the States concerned within the 60-day deadline,” Prisoners Defenders observed on Tuesday. “If these responses had arrived, they would have been published by the United Nations. But this is not the case as of January 2, 2024.”