John Rubino is a former Wall Street financial analyst and author or co-author of five books, including The Money Bubble: What to Do Before It Pops and The Collapse of the Dollar and How to Profit From It. He founded the popular financial website DollarCollapse.com in 2004, sold it in 2022, and now publishes John Rubino’s Substack newsletter. John joins the podcast to discuss owning real assets, how to think about financial bubbles, and the new supply and demand dynamics in the gold and silver markets.

John’s substack: https://rubino.substack.com

Follow Monetary Metals on X: @Monetary_Metals

Additional Resources

Earn 12% in our Silver Bond offering

Earn Interest on Gold and Silver

Earn Passive Income in Gold and Silver

Podcast Chapters

00:00 Introduction

00:38 Monetary Metals’ Gold Exchange Podcast

01:12 – Jon Rubino: Financial Bubbles Expert

02:37 – Understanding the Everything Bubble

05:02 – Commercial Real Estate’s Role in Financial Crises

12:37 – Earning a Yield on Gold and Silver

13:15 – Capital Changing Hands

21:12 – Silver’s Dual Role: Industrial and Monetary Metal

27:49 – Potential Upside and Stability of Precious Metals

33:12 – Bear Case for Gold and Silver

41:46 – Future of Negative Interest Rates and Real Assets

45:42 – Is Everything Actually Fine

50:36 – Question for Future Guests

51:26 – Follow John and Monetary Metals

Transcript

Ben Nadelstein:

Welcome back to the Gold Exchange podcast. My name is Ben Nadelstein of Monetary Metals. I am joined by special guest, John Rubino, publisher of the John Rubino Substack, which you have to absolutely read. Description and link are there. John, I want to start right away. People don’t know you. What should they know about John Rubino? Why should they subscribe to the Substack? And how did you come to the metals and mining space?

John Rubino:

Hey, Ben. It’s good to meet you, first of all. Congratulations on your success at Monetary Metals. Very impressive. I’m somebody who’s basically inadvertently been involved in financial bubbles since the 1970s, really. I a baby gold bug back then and watched gold and silver soar and become bubbles and then crash. And in the 1980s, I was a junk bond analyst, just as that sector of the financial system became a bubble that almost destabilized everything. In the 1990s, I was a tech stock columnist for an online magazine where I was the resident bear as the tech stock bubble blew up and then crashed. In the 2000s, I wrote a couple of Gloom and Doon books, one on the real estate bubble and one on the banking system and gold and everything. Now I’ve got a Substack where I’m chronicling basically the end of the fiat currency experiment. It’s been a lifetime of watching bubbles grow and expand and cause trouble and then blow up. Here we are again with the everything bubble getting ready to burst. I think it’s a good way to go out for me. Probably the Substack that I’m running right now will probably be the last piece of writing that I do, and it’s going to bookend nicely with the stuff that I did before.

Ben Nadelstein:

Well, it’s great. You’ve got to chronicle all these different bubbles as they’ve come on. So first, I want to talk about this idea of the everything bubble. What would you consider or how would you define the everything bubble? I know a lot of people say, Well, okay, maybe markets are a bit frothy or real estate’s a bit frothy or whatever, miners are a bit frothy. But how do you define an everything bubble?

John Rubino:

Well, basically, the origin of it is that we’ve been taking on more and more debt under a fiat currency system. That’s just how it works. Everybody borrows more and more money. So that the amplitude of each boom and bust have gotten bigger and bigger. But the previous booms and busts were sector-specific. It was one thing. It was junk bonds, or it was tech stocks, or it was real estate. But now we’ve reached the point where the numbers are so big. There’s so much debt in the system, which is to say there’s so much bad debt in the system that we’ve blown up a bunch of We’ve got different bubbles simultaneously. We’ve got tech stocks now, which are as big a bubble as they were in the 1990s. We’ve got real estate where house prices are higher relative to income than they were in the 2000s. We’ve got government bonds, which is almost by definition, with the amount of debt that’s out there, government bonds globally are a bubble. We’ve got lots of other things that are out there that are quasi-bubbles or real bubbles, and they’re all getting ready to burst at the same time.

So when people call it the everything bubble, James Tuck at GoldMoney and I co-wrote a book called The Money Bubble, which was our term for this. So in the sense that it wasn’t just one sector anymore, it was money that was the bubble. Now, the term as the everything bubble, since we’ve got multiple bubbles within the fiat currency bubble itself. And I think that that’s how you know it’s the end of the process when you’re not dealing with single bubbles anymore, but you’re dealing with sectors everywhere you look that have bubble characteristics and therefore are going to end the way all bubbles end. Then it becomes a question of what’s the catalyst? Which bubble blows up first or collapses first and takes everything down with it? We could talk about possible catalysts if you want, because that’s an interesting discussion, although it doesn’t really matter if you’re assuming that the whole thing blows up at some point, because we all end up in the same place then, no matter what starts it. But I think the idea of what’s going to start it is a very interesting one.

Ben Nadelstein:

Yeah, I do think some people say that there’s lots of kindling. It’s just which one of those sparks the fire. So let’s jump into one, which I think a lot of people, at least in the United States, have been keeping an eye on, which is the commercial real estate market. So obviously, when interest rates raise higher, that’s generally pretty bad for things like gold, which other than net monetary metals, don’t pay a yield, or things like real estate, which are very mortgage or rate or debt-heavy. And so when rates change, that really changes the calculus that goes into things like commercial real estate, topped by the fact that we have this global pandemic, lots of people left their in-person jobs for online jobs. We can do a Zoom here and have a fun conversation without flying all the way to see each other. And so the need for commercial real estate, not only has the demand fallen off a cliff, but the question of, okay, with a 5% rate handle, can we really make the commercial real estate market work? Where do you see that link in the chain to something like a crisis?

John Rubino:

Well, office buildings in particular are a big problem in commercial real estate right now. As you said, a lot of them went up with very easy money. Now with higher interest rates, they need to be to be financed, but the cost is much, much greater. Then the pandemic came along, and a lot of people got a chance to work from home, found out they really like it. They don’t want to go back to the office. A lot of office buildings aren’t full enough to generate the cash flow necessary to cover the related debt and operating expenses. What’s happening now is a lot of buildings are changing hands at much lower prices. A building that was $100 million when it was built is now being sold for $12 million. You see things like that all the time, which means that there are unrealized losses out there in the office sector that run to the hundreds of billions of dollars. A lot of, especially local and regional banks in the US, have that paper on their balance sheets. They have these big unrealized losses that when the office buildings change hands, will have to be realized. They’ll have to report the losses on the asset-backed bonds that they hold or whatever, or the direct loans to these buildings.

The big risk is that they report these numbers. That spooks their depositors into pulling money out of a bank, a given bank. The bank then has to sell more of its depreciated assets in order to pay off its depositors and report those losses, which leads to a run on the bank, which leads to a run on every similar bank in the US, collapses the whole sector and forces the federal government into a multi-trillion dollar bailout. We saw the beginnings of that with the Silicon Valley Bank a year or so ago, when the government stepped in immediately, bailed out three or four banks, and that put an end to the problem temporarily, but it didn’t fix the underlying problem, which is all this bad paper on the balance sheets of these banks. The coming year is probably when this comes to a head because it’s right there. A lot of these buildings are not viable. Something has to happen to make them viable, which is they change hands at a much lower price, and then they can go forward under new management in a profitable way. But the old owners have to take big losses. That’s what we’re looking at in the year ahead.

That could easily be the catalyst for a big crisis in the financial markets, because if local and regional banks start to blow up, it won’t be just limited to that sector because people will start looking around going, Well, if they could blow up, who else could blow up? Who else is in danger of being insolvent in a really public way? We need to get our money out of that sector, too. Then it spreads and something else in the everything bubble bursts and something else. There you go. You’ve got this avalanche that governments could try to stop, but it’s going to take tens of trillions of dollars of newly created currency. Then that shifts the problem over to the currencies themselves. We get, excuse me, another 2022 when official inflation goes up to double-digit levels, almost, and the real inflation in the sector or in world goes up to 15 or 20%. That’s a death nail for fiat currencies right now. If we get something like that, that people see as unfixable, which it would be, because The only way to fix a collapsing currency is to raise interest rates. But if you raise interest rates, you blow up all the bad debt that’s out there, and you spike the interest costs of the world’s governments, leading a lot of governments to be insolvent.

Once people see that, then that’s when the everything bubble blows up and the fiat currency experiment comes to a fiery end. I think that the 50-some-year experiment with currencies that aren’t backed by anything in a world of fiat currencies, not just one country trying this experiment and having it blow up in their faces, but the whole world trying it at the same time. That experiment ends. Then the question becomes, how does it end and where do we go from there? Which I think is a lot more interesting, really, than how does the everything bubble blow up? Because we’ve seen so many bubbles in the last 30 or 40 years. We know how bubbles burst. Prices get out of control. The financial games in the sector that are being played become untenable, and then the bubble bursts. We know that’s how bubbles go, and we know we have multiple bubbles now that are in danger of that. But the real interesting question is, what do we do after the fiat currency experiment fails? And I think that’s a fascinating debate with good possible outcomes and horrendous possible outcomes. So I think we all need to be paying attention to that, both from a public policy standpoint and from a personal standpoint, because you got to invest for this.

Choosing not to invest for these kinds of outcomes is the same thing as investing badly, because not choosing is still a choice. So we all, as individuals, have to figure out how we want to position ourselves for this huge sea change in politics, geopolitics, and financial policy. That’s what my Substack newsletter is about, basically, looking for actionable ideas in a world that’s changing in such a dramatic way that the old risk-free strategies are now the opposite of risk-free and so on.

Ben Nadelstein:

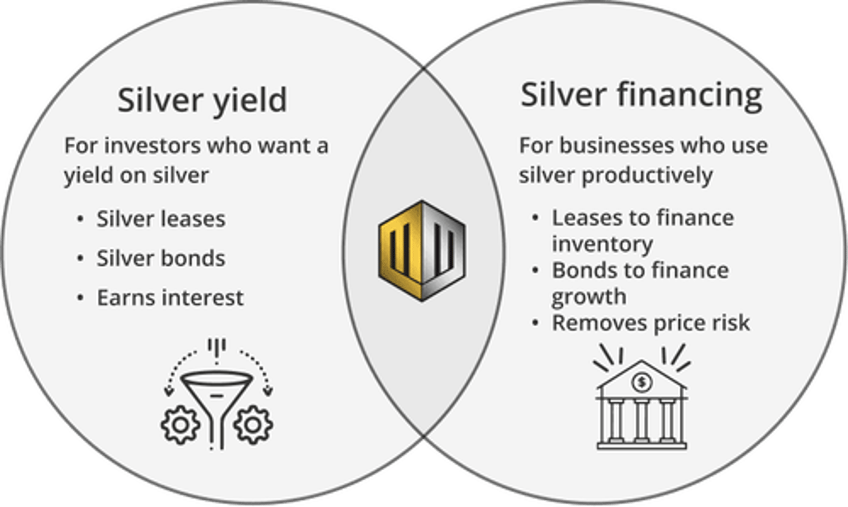

What we’re actually doing at Monetary Metals I would consider one of those actionable strategies. We pay a yield on gold and silver, so it’s a free market rate. You have your gold and silver. We offer you opportunities on the platform to earn a yield, whether that’s in a lease or a bond. Those interest rates reflect the risk or the duration as they should in a free market. And they’re not set by someone like the Federal Reserve. We just offer you platform products, and then you say, Okay, I like this one. I like that one. And you can get a rate and an interest rate that reflects your preferences. And The land is set by you and your market preferences, not by some bureaucrats at the central bank. So that’s one actionable item.

Can you give us some other actionable items where you think people might be interested in looking? Because at the end of the day, just because the price of these goods has changed, like we said in the commercial real estate market, something goes from an $100 million complex to maybe a $12 million complex. The actual capital is still there, the buildings are still there, the materials are still there. It’s just who owns it and at what price. So can When you talk about maybe in this post-game action where, okay, maybe the commercial real estate bubble pops or some of this everything bubble begins to deflate, where do you see those changing hands? Is it an East to West question where Western investors now are holding the bag while Eastern investors are grabbing it up? Or is it something different where different people, let’s say, who own gold and silver are profiting, where people who own tech stocks are not? How do you see that distribution changing?

John Rubino:

Well, what we’re seeing right now, and this is something that we as individuals can emulate, is we’re seeing the world’s central banks aggressively buy gold and to an extent, silver, because they see this coming. They also see that the US US has weaponized the dollar. We’re using it as a weapon to keep other countries in line, and that’s really offensive to a lot of other countries and threatening to a lot of other countries. So combine those two things. We’ve got a currency crisis coming in which the traditional central bank reserve assets lose value in a disorderly way, and you’ve got a rogue empire out there using its global reserve currency to threaten other countries. Put those two things together and you got an incentive to move to stores a value that, first of all, survive and thrive during currency crises and aren’t political. Gold in a central bank’s vault is not a political statement. It’s a neutral asset that all the central banks can own to protect their local and national currencies without having to take sides in the geopolitical conflicts out there. So that’s a big incentive to buy gold. And central banks have been buying it really aggressively in the last few years.

I think in the last two years, central bank buying has accounted for about a thousand tons of gold, which is a lot in a market of 2,500 tons being mined each year by the world’s mines. That’s a very big deal. And it’s part of the reason why the gold price is going up suddenly and dramatically lately, because central banks, they’re not so price sensitive. They want to get a percentage of their reserve assets in gold, and they’ll do it at whatever price they have to pay because they see the end to all of this. As individuals, we can emulate the central banks by buying physical gold and silver and storing it in a safe place. I think that’s the bedrock of a wise financial life right now is gold and coins that you buy, you have delivered to your house or wherever, and you put them in a place that you know about and maybe one other trusted person knows about. And that’s your generation of wealth. That’s the stuff you own that will hold its value going forward. If it’s 10 years or 50 years or 200 years, your successors are going to be able to have at least one thing that’s still valuable.

And then from there, you can branch out a little into real asset investments that may be a little bit riskier, say, gold and silver mining stocks or what you guys offer or oil wells, energy stocks, things like that, copper stocks, commodities in general, real things that governments can’t just make more of on an electronic printing press that will tend to go up when we debase the measuring stick for their prices. If we make the dollar less valuable, then an oil well gets commensurately more valuable when priced in dollars. You want to own things like that. Then there are things that have real-world utility but are also real assets the governments can’t create out of the air, which are farmland, a really well-chosen rental house, something like that. That’s a thing that can be used and therefore stays valuable even when the currency does weird things. You can branch out Starting from physical and into financial assets that represent physical real assets, and then build a portfolio that way. But nothing is guaranteed in life. Not every single real asset is going to go up dramatically. But if you have a nice portfolio of them that’s diversified within that universe, you probably do just fine.

You’ll probably end up protecting yourself and your family and maybe building considerable wealth if if you get it just right. That’s the intellectual challenge, getting as close to just right as possible with a portfolio of real assets. You see a lot of people out there doing it based on the demand for, for instance, gold ETFs right now. Suddenly, individuals are buying more physical precious metals ETFs. I think that’s a good sign. I think people are catching on now and taking a simple step that they understand in in that direction.

Ben Nadelstein:

Yeah, and one point that I really want to hammer home, and we do mention it in many episodes, is the actual value of this asset that you own, if you call it a real asset, whether it’s gold, silver, farmland, even an oil well, that actually produces some real thing that you can’t just print, you can’t just go on an electronic digital signature and say, make 50 more of these. You actually have to do some real either work to get it or it has some actual real value that can be exchanged either throughout time, which gold and have been monetary assets throughout thousands of years. Or currently, people love oil. They use it for farming equipment, for cars, all these things. So it has some actual value to it. And when people realize that central banks can just basically paper over any problem with these electronic currency, that makes a lot of people doubt the value of the currency going forward, whether that’s because of inflation or debacement. And one analogy I often use is, if you live in Venezuela or if you live in Argentina, a place with a really weak currency, it is not the case that your real estate has just suddenly 10Xed in value or that your little shop that sells bagels or whatever in Venezuela, maybe they have great bagels there, it has suddenly become a thousand times more valuable.

What’s actually happened is that your currency has become 10 times less valuable or a thousand times less valuable. And that’s either because of central bank machinations or inflation or some combination of the two. But it’s not that your wealth actually increased because you’re using a measuring stick or a measuring rod that is really bad. The same way that if you had a measuring stick that was made out of rubber bands, that would be a horrible way to try to build a house or to build wealth. So when you use something like a real asset, usually I say gold or silver, you can actually see if your wealth is increasing or not, because gold priced in Yen would show you, oh, wow, it’s not that the Yen got so much stronger or weaker. What actually happened was my gold retained its value, the things around it moved up or down in and I can see whether I got more wealthy or less wealthy. So before we move off the metals and the miners here, we talk about silver. So some people own gold, and they measure their wealth in gold. They say, Okay, I’m going to use gold as my capital asset.

But silver is also a monetary metal. What do you see as the argument for silver? Generally, central banks don’t buy silver or in the same quantities that they do of gold. Part of that is because of the value to weight ratio. You can have $2,000 worth of gold and maybe a coin, but $2,000 worth of silver, you’re going to have a lot of silver. So of course, that has storage costs. So where do you see the play for silver as a monetary metal, but a little bit different than gold?

John Rubino:

Well, silver has two basic stories, and either of them are enough to make it something that you really want to own. And first of all, it’s an industrial metal. It’s got a lot of characteristics that make it useful, if not absolutely necessary for microchips and for energy generation. The list It goes on and on. And there’s barely enough silver coming out of the world’s minds right now to satisfy all the industrial needs for silver that there are. And solar power is a wealth Two things are happening that are really turbocharging that process. First of all, solar panels use silver, and the world is slapping solar panels up everywhere you look. And so the amount of silver that’s gone into the solar sector has spiked in in the last few years to the point where it’s maybe one-third or one-fourth of overall industrial demand, which is just huge for a new source of demand to come into the market like that. Then you’ve got the AI revolution right now, Everybody in the world is trying to build data centers to run their newborn AIs on. And that’s leading to, first of all, a lot of demand for silver in the chips that go into this, and then a lot of silver in the electricity transportation system that is required to build all these data centers and satisfy them.

So it’s not going to end. The industrial uses for silver will continue to grow, and they alone will strain the ability of today’s minds to produce enough silver for it. But then you’ve got, like you said, the fact that silver is a monetary metal. When there’s a currency crisis, people basically go through this thought process. They buy gold first because gold is the big daddy in the safe haven asset world. It’s the thing everybody immediately thinks of when they’re worried about their currency, and gold’s price goes up. But then people think, Well, what else is like gold? Because gold is so expensive now. Oh, yeah, silver is almost the same thing. But as you said, look, 2,000 bucks or 3,000 bucks will get you one crew grand, one coin that fits in the palm of your hand. Same amount of money gets you a table full of silver coins. Silver is also in a really serious currency crisis scenario where, for instance, if you’re in Venezuela or someplace where the money just doesn’t work anymore, silver is much more useful as a day-to-day transaction mechanism because it’s small change relative to gold. With gold, you can take a few gold coins out and buy a used car, but you’re not going to take a gold coin to the farmer’s market.

You can take silver to the farmer’s market. One silver coin, when we really get going here in the precious metals bull market, one silver coin is going to buy you all the food you need for a month, probably. People start buying silver in place of gold. Silver is a very thinly traded, small illiquid market, so that when extra money comes in on the investment side, it creates a deficit, which is where we are now. There’s an overall deficit in the silver market in the sense that people are buying more silver than the world’s minds are producing. And that deficit risks turning into a shortage, which causes panic buying and causes the price of silver just to go straight up. And that’s happened in the last two cycles, one in the 1970s, one in the 2000s, where silver went parabolic at the end of the process. Now the numbers are way bigger, and the industrial demand for silver is way more extreme. The potential investment demand for silver, in other words, regular people who can’t afford gold anymore, panic buying silver, that’s potentially way bigger than it’s ever been in the past. You have the potential out there for a silver shortage that leads to a parabolic price spike that’s much bigger than the ones in the past.

So we could see silver go from $40 or $50 an ounce to $100 or $200 an ounce because that’s what happens when something catches the attention of an overliquified world. You saw it with Bitcoin, we saw it with NVIDIA, we saw it with a lot of the meme stocks. Silver could become the equivalent of a meme stock very easily when people realize that it’s super cheap compared to gold, you need something to protect you against a collapse in currency. And that’s almost all there is. What else you’re going to buy, if not silver, because gold is out of reach by now. And that’s the situation we could be in in the next couple of years. And I don’t think you need anything remarkable for that to happen. Industrial demand is what it is, and it’s somewhat cyclical, but new technologies tend not to be cyclical victims because, for instance, during the Great Depression, nobody had any money yet. Radios and cars sold like crazies because those technologies whose time had come. And today we’ve got solar power and AI, which fall into that same category. We’ll probably keep buying them no matter what. And so that really puts a floor under silver demand.

It can’t fall very far from here, and therefore, its price isn’t going to be that volatile on the downside. You could have definitely you can have corrections from here and from where it goes in the next couple of years. There can be recessions which lead to equities bear markets, which temporarily knock down precious metals. But generally, precious metals, especially Silver, are going to be the things that are volatile to the upside much more than to the downside in the next 5 to 10 years.

Ben Nadelstein:

So a question for you. Before we have you make the bear case for both gold and silver, I want you to give your just opinion or I guess your prediction. Do you see silver, let’s say in the next decade, think silver will still remain a monetary metal, or do you think it will be seen more as an industrial or precious metal because of all these industrial demand? So for example, I could see a world where gold becomes much more tokenized. It’s easy to cryptify your gold. And so you can spend gold at Starbucks. You can spend 0.006 of an ounce at Starbucks. Even though the value of gold is really high, the payment method you’re using makes it easy to spend your gold. And so that would maybe lower the reason for having silver as a monetary metal. And on the other side, there’s that industrial demand for silver, whether that’s solar panels, AI or tech. So do you think in the next 10 years, we’re going to see silver’s narrative changing from a monetary metal to just a precious metal? Or do you think that monetary component is always going to remain?

John Rubino:

Well, I think it becomes more important because the tokenization of gold might allow gold to become money or currency, like the dollar is now a tokenization of, or it used to be a tokenization of gold. You could see something on a blockchain related to gold that we use as a medium of exchange. But that’s not physical. That only works as long as the Internet is up and running, as long as your cell network is up and running. And those are not guarantees going forward. There are all kinds of technological and geopolitical and cybercrime and cyber terror events that could lead to a medium to long term breakdown in our ability to use digital currencies because we don’t have access to the Internet, we don’t have our cell service. And that increases the need for physical money, which would be silver. If you understand the concept of gold and silver and what they are, and your gold is tokenized and you’re happy to leave it in a vault somewhere and then spend it on your phone or spend it on your computer, then you still need something physical. Or when it really hits the fan and you don’t have access to your tokenized gold and you don’t trust your paper currency because it’s collapsing in value, well, silver is the obvious choice.

Silver is medium to small denomination currency when the time comes. So Nobody has to own some physical silver in that scenario. Right now, very few people own physical silver because they haven’t been thinking this through. They don’t obsess over this stuff the way you and I do, and they haven’t come to these conclusions yet. Let a critical mass of people, and it doesn’t have to be a big critical mass in the US, say 30, 40, 50 million people, figure this out and decide that silver is just one of the things they want to own as part of their prepping. Then that taps out the market. There won’t be enough silver to satisfy that demand. Silver, when people are treating it as a monetary metal, that will tip the silver market over into much higher prices. Once that happens, then, for instance, the solar panel makers have to figure out a way to use less silver. You get that a dynamic where in some senses it becomes less of an industrial metal because at a high enough price, maybe it’s worth substituting copper or something it. In the solar panel industry, they’re doing that in a gradual way.

The amount of silver per kilowatt hour in a solar panel is going down a bit over time, and they’re prepared if they have to. Silver is $200 an ounce, then they’ll pull out some things that they’re working on now and they’ll mass-produce them, and silver will be less of a factor in solar. I can see the monetary side of the becoming bigger for silver, even though the industrial side stays big. But the monetary side is much smaller right now, and it’s potentially a lot bigger. I think that’s one dynamic that’s very possible, where Silver stays very useful in a lot of industrial sectors, but it also becomes a form of money in the mind of a lot of people, and that becomes a bigger deal for existing silver supplies.

Ben Nadelstein:

For those who have physical silver or are interested in earning a yield on it, Monetary Metals has the world’s first silver bond since 1834. It pays 12% annual yield on silver paid in silver. If you’re an accredited investor and interested, you can check that out at our website, monetary-metals. Com. Now, John, I want you to do something difficult, which is I want you to make the bear case for both silver and gold. We’ve heard the bull case. I want You want to hear the sober, John Rubino, narrow case. Hey, okay, here is what I think could happen to gold and silver. It’s realistic, and I think this could actually be a bear market for both gold and silver. I’ll let you fire away.

John Rubino:

Well, there are two bear market scenarios for precious metals. One is short term, one is long term, and they’re both serious enough to pay attention to. And the short term one is that we have that recession that we’ve been threatening to have for such a long time. That leads to an equity spare market. And when stocks tank, especially big tech, that pulls everything else down, including gold and silver. Gold and silver both dropped dramatically in that a scenario. And we’ve already seen that in the last two cycles In 2008, stocks tanked and gold and silver fell hard. So did the gold and silver miners. It was just a brutal takedown of the precious metals market. Then in 2020, when the pandemic hit, and it It looked like we were going to maybe go into a global depression because all the governments were shutting down their local economies, gold and silver did the same thing. They tanked… Well, stocks tanked and then gold and silver tanked, and that took down the gold and silver miners. You saw two really dramatic bear markets in precious metals in just recent living memory. So could it happen again? Absolutely.

Tech stocks are, as we talked about before, they’re a bubble right just as seriously as they were back in the 1990s. And if they roll over, for instance, one big thing could cause a tech stock bubble to burst here. And that is that AI turns out to be enough hype, not pure hype, but enough hype to lessen its impact on the near-term economy and the near-term financial markets. In other words, yeah, AI is pretty cool, but who’s making any money off of this? Not very many people. And then everybody spent hundreds of billions of dollars on AI already, and they have to scale back their spending because they can’t justify it to the board. And then NVIDIA goes down by 50%, which still makes it a wildly overvalued by historically norms tech stock. But that pulls down the rest of the market. Gold and silver tank could very easily happen in the coming year. So that means one possible scenario is that silver and gold both drop by 30 to 50 in the not-too-distant future. Now, you deal with that short-term risk by not jumping in with both feet. You dollar cost average your way into your physical silver or your mining stocks, and you use low-ball bids to…

At the end of every investment recommendation I have on my sub stack, there’s a standard paragraph that says this, Do not just load up the truck right now. Do dollar cost averaging, do low-ball bids, write to get lower prices, things like that, because you don’t know what’s going to happen in the short run. I think that’s a real scenario that I think is probably a 50/50 probability right now where we have a recession in an equities bear market, and then it affects precious metals. The longer term problem is that the world’s governments are basically at a crossroads right now. They have screwed things up to the point where a pain-free transition back to an organic technically growing stable economy is out of the question. What’s left is a choice of two crises. One is the Weimar Germany-ish hyperinflation, where we try to inflate our way out of all our bad debts, and that impairs the currencies and causes an unstable, all off the tabletop event for the currency markets. That’s That’s where you really want to own precious metals. That’s the positive scenario for gold and silver. The other very real possibility for the world governments is that they choose a 1930s-style deflationary depression by refusing to try to inflate away their currencies, which would lead to a lot of bad debt going bust, which knocks down the other dominoes and so on until you get rid of your debt, but you get rid of it through default.

And so you have a deflationary crash. And so that would be the short term scenario for precious metals with an equity spare market, et cetera, et cetera. But it would be writ large. It would be five years or more of deflation. That would be tough for silver, and it would be ambiguous for gold, because in the Great Depression, gold actually got more valuable because it was money back then. In deflation, money becomes more valuable. If people start perceiving that gold is money, then gold could hold up in a scenario in which we’ve got a 1930-style deflationary crash going on. But it’s also possible that gold tanks along with every other financial asset out there. That’s not a purely positive scenario for gold, and it’s possibly a really negative scenario for silver. I think that’s a 10% or 20% probability because government’s impulse is always to try to inflate away their problems. It’s highly unlikely that the world’s governments are going to say, Well, we’re just going to go to balanced budgets right now, and we’re going to protect the value of our currency, keep it from falling off the table with higher interest rates. That’s technically possible, and it It would probably be the less painful in the long run thing to do.

But very few politicians are going to sign off on something like that. So it’s possible, and maybe it happens by accident, where some of these bubbles burst in a way that’s so disorderly that governments can’t control the consequences, but it’s least likely. It’s less likely because governments can create money out of thin air or currency out of thin air. It’s not clear what would stop them from We’re saying, Okay, we’re going to increase the money supply by 72% this year because we saw that number somewhere and we like it. You can do that with a mouse click. It’s much more likely that we try to inflate our way out of what’s happening. But we can’t lose sight of the fact that The deflationary crash scenario is a real possibility, which is why you don’t just own 100% real assets. You need to spread or 100% in one or two categories of real assets. You need to spread it around because nothing is absolutely guaranteed in life. There are probabilities, but look at any Super Bowl in the last 20 years or any Championship boxing match or whatever. The underdog can lose, and a big underdog can lose.

And it’s the same way with financial scenarios. Things that just don’t seem probable right now can still happen. So diversification is crucial. Whatever you do, you need to spread your bets around, both in terms of assets and in terms of geography. If you have the ability to move money overseas, very good idea, because you can’t know which government is going to go craziest on which schedule. Something like extreme wealth taxes or capital controls or any number of other things could very possibly happen in the US. Us. People in the US who are listening right now, if you have the ability and the knowledge to be able to move some money to Switzerland, Singapore, Costa Rica, something like that, it’s worth looking into.

Ben Nadelstein:

Now, in terms of some of the tools, if you want to call them that, that central banks and governments have in their toolbox, where do you see negative interest rates? Do you think that is something that will actually likely or potentially happen in the United States? Is there actually a probability that there will be nominal, not real, but actually nominal negative interest rates? Or do you think that’s a tool where they say that it’s just not worth using that? Where do you see that negative interest rate factor in?

John Rubino:

Oh, yeah. I think it’s possible, if not probable this time around, because remember, in the last four or five cycles, we’ve lowered interest rates further than in the previous cycles. This last time around, we got to zero, at least at the short end of the yield curve. It would fit the pattern that the next bubble bursting, the next crisis, is much bigger than previous crises, which leads to a bigger response from the government, which in interest rates would have to be negative, because we’ve already been to zero. Yeah, you could easily see negative interest rates in the US and also in the rest of the world, because we’ve already seen dramatically negative interest in Germany and Japan. Remember, what was it? Like 35% of global government debt had a negative yield at one point in the last cycle. As crazy as that sounds. The idea that we go further than that isn’t even remarkable since we’ve gone further than the previous cycle or all the most recent cycles. I think we could see negative interest rates going forward. That’s incredibly It’s really good for real assets, of course, because it means the carrying costs of real things.

If you borrow money to buy a real thing, then maybe they pay you because you’re borrowing money at negative 2% or whatever. That was the case for the Japanese government for a long time. They borrowed money at negative rates, which meant government cash flow went up when the government borrowed money. There’s no reason why other entities in the global financial system don’t want to deal like that going forward. I would love that. The big banks would have a ball or Wall Street more specifically, because if you’re a private equity company and you’re rolling up dental practices or something like that, if you can borrow money at a negative rate, you can roll up everything inside. You can make insane amounts of money using negative rate loans. The financial community, which is basically in charge of government monetary policy, would probably love another stretch negative interest rates. They’ve seen how it works. They see exactly how you get insanely rich using that cheap money, and they would love a redo of the previous decade. So yeah, totally possible. If that’s the case, You really want real assets in that a situation. You want farmland and gold and silver and oil wells and all of the above.

The scenarios we’re talking about now It would easily include negative interest rates as part of a mix, but they’ll certainly include really extreme government action to reliquify the system and try to keep the bad debt from metastasizing into much more bad debt. So they’ll do extreme things. And the fact that you can’t know exactly which three things or which crazy things means that you really need to think through your specific mix and how it works for with your own risk tolerance and with the other capital that you’ve got available and everything. It’s all situations specific. There’s no one roadmap, no one formula for how you position your sofa this stuff. But there are general ideas which you can then translate into specific things that work for you.

Ben Nadelstein:

Let me push back now. I’ll be a critical observer. I’m listening to the podcast. Okay, yeah, these guys, they like gold and silver, and they like real assets. And I hear what they’re saying about the dead and all that stuff seems to make sense. But I’m looking at my 401k, which is S&P 500 and all this stuff. It’s at an all time high. That seems great. Unemployment is near all time lows. We’re practically have full employment. That seems great. And Jerome Powell said last week that they might be cutting rates at September. So everything seems to be fine. It seems like there was a soft landing. All these people who are running around with chicken little with their heads cut off saying, Oh, my goodness, there’s going to be a crash. Those guys have been wrong for the last year. I think everything is basically fine. What’s the point in owning real assets? What’s the point in owning gold and silver? Now, I’m going to take it to John. I’m the critical observer. How do you answer someone like that?

John Rubino:

Well, there is a time for financial assets. When you’re in the early part of a credit expansion, then you want to own things like government bonds and bank stocks and even money market funds and things like that, because those things to do just fine when interest rates are falling and the government is creating lots of new currency and throwing it out of the banking system. Because what the government does when it eases is it gives money to big banks who then give that money to their preferred super-rich customers who go out and buy the stuff that rich people buy, which is stocks and bonds and trophy real estate and fine art. Those things soar in price during the upward-sloping part of a credit cycle. And when things roll over, in other words, when all the debt that was created as part of the credit expansion starts to go bad, and then you get a recession and you get an equity’s bear market, that’s a bad time to own the things that have gone up for the past 10 years. If you’ve got a portfolio that’s got tech stocks in it and even recently, government bonds, and you’ve made a lot of money, you’re doing really well, you did exactly what you should have done in that cycle.

I’ll definitely grant you that I personally was too early in calling an end to this. I thought 2016, 2017, the numbers had gotten big enough that we probably weren’t going to see another leg of equities boom market, but we did. Part of that was because the pandemic hit and the government just went crazy with money creation. We increased the money supply in the US by 40% to 60%, depending on the monetary index that you’re using. That money had to go somewhere, and a lot of it went into financial assets. What that did, though, was just raise the price of those financial assets to the point where if financial history means anything, they’re primed for a crash. Anytime they’ve gotten this expensive in the past, you can look at it on a chart. The next thing that happened was the 2000 bursting of the tech stock bubble or the 2008 bursting of the housing bubble. When things get this expensive, you have to have a redo in the system to get rid of all the resulting bad debt. I would argue now that we’re in that place of valuation that usually proceeds a big equities bear market.

Maybe history won’t repeat this time around, but history is based on a version of reality. In other words, financial and economic laws can be bad, but they’re hard to break. When you end up with a certain amount of debt relative to income, trouble happens. When house prices reach a certain level relative to the incomes of potential home buyers, that market rolls over. That’s where we are now. It’s completely possible that this time It goes even further because I did think it couldn’t go any further after mid to late decade, previous decade. But history says that it won’t go much further from here. Even if you don’t buy into the real asset thing in any way, you might want to be raising some cash. In other words, rewarding your sofa investing so successfully in the previous decade by raising some cash and putting it in a place that will protect your family if things don’t continue. There are lots of things you can do with cash. You can prepay your kid’s college education. You can pay off existing debt. Do things like that. That way, you still get some benefit. Even if stocks go up and you miss the final leg of this bull market, you’ve done something that has some utility that helps somebody in your family with the cash that you raise.

Then you won’t feel so bad about missing the last blow-off leg of the equities bull market.

Ben Nadelstein:

John, it has been a fascinating conversation. I have a final question for you, which is, what’s a question you think I should be asking all future guests of the Gold Exchange podcast?

John Rubino:

That’s a good one. I would say ask them if they personally have enough physical assets to survive and thrive in a financial asset crisis and how they define those physical assets. Because you interview a lot of really smart, successful people who have chosen different answers to the questions that you and I have been asking today. So I would be interested in hearing if they’re willing to talk about what they’re doing personally, what they are doing.

Ben Nadelstein:

For those interested earning a physical yield on their physical gold and silver, you can out monetary-metals.com. Jon, where can people find more of your work?

John Rubino:

I’m at rubino.Substack.Com, and I publish a newsletter there that looks for answers to the whole, what do you do going forward were questions that we’ve been talking about.

Ben Nadelstein:

Link to your awesome substack will be in the description. John, it has been a pleasure talking with you. Hopefully, things continue to look interesting, and we’ll have you back on the show.

John Rubino:

Great. Thanks, Ben. Look forward to it. Thank you!

Additional Resources for Earning Interest in Gold

If you’d like to learn more about how to earn interest on gold with Monetary Metals, check out the following resources:

In this paper, we look at how conventional gold holdings stack up to Monetary Metals Investments, which offer a Yield on Gold, Paid in Gold®. We compare retail coins, vault storage, the popular ETF – GLD, and mining stocks against Monetary Metals’ True Gold Leases.

The Case for Gold Yield in Investment Portfolios

Adding gold to a diversified portfolio of assets reduces volatility and increases returns. But how much and what about the ongoing costs? What changes when gold pays a yield? This paper answers those questions using data going back to 1972.

© Monetary Metals 2024