Whether in Roman times or now, public life entails risks. We can't let that stop us

The cycles of history move faster today than in the past — and they may not repeat, but they do rhyme.

The Roman Republic lasted almost 500 years.

But the assassination of Julius Caesar in the Roman Senate in 44 BC, over fears that he was becoming too powerful, sped up the process of decay. As politics got dirtier and more dangerous, many leading political and military figures withdrew from the public square, compounding the chaos.

WHY ARE MEN OBSESSED WITH THE ROMAN EMPIRE? HISTORY EXPERT SAYS IT’S A ‘VERY AMERICAN THING’

Both Cicero, a Roman senator, and Varro, the great Roman scholar, criticized those who absented themselves from public affairs, noting that many spent lavishly on fishponds. Varro wrote that these were "built at great cost, … stocked at great cost, and … kept up at great cost." While Cicero mocked them as "piscinarii" meaning "fish fanciers."

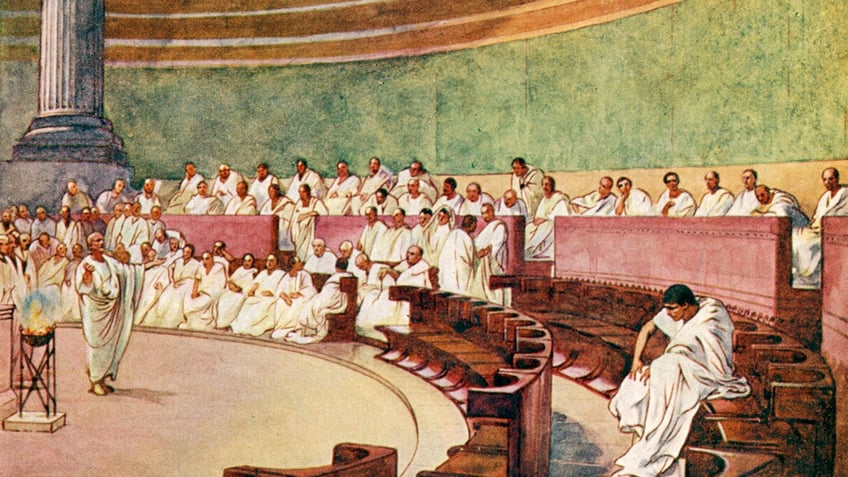

The Senate during the Roman Empire assembled in a temple with council members wearing white tunics and togas. (J Williamson/Culture Club/Getty Images)

Only 17 years after Julius Caesar was murdered in the Senate, Caesar Augustus commenced his reign as emperor over the republic’s ashes.

America’s constitutional form is 235 years old — some half the span of the Roman Republic. Yet America has a growing multitude of its own piscinariian diversions, made all the more tempting for those otherwise inclined to public service.

If Hobbes suggested that, without government, life would be "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short," then being in government threatens the same, at least for those whose predilections run counter to the dominant left-wing culture.

Elected and appointed officials, as well as scholars and pundits, expose themselves through their participation in public life to a myriad of discomforts ranging from the threat of lawfare aiming to bankrupt or even imprison, to cancelation of one’s ability to earn a living, to online harassment. All of these threats have sprung up or amplified in the past 30 years.

I just had my own brush with a literal fishpond.

As is tradition, apparently, I happened to ponder ancient Roman during a recent trip to California. It was my first visit back to Orange County — to the area I had the honor of representing in the State Assembly from 2004 to 2010. I addressed the Republican Party county central committee and saw many old friends.

The next day, before I flew back to Texas, I visited Fashion Island in Newport Beach, home to several wonderful fountains and a beautiful Koi pond that my youngest daughter, then 3, fell into back-first when she was startled by a dog’s bark. Given the longevity of Koi, there were likely many alive when she fell in over 20 years ago.

As I walked away from the Koi pond, my mind flooded with nostalgia for the place and its time in my family’s life. I was also struck by its serene beauty. But then I started to think about what we left behind and mused about returning to the land of fishponds.

Augustus Caesar, first Roman Emperor. Marble statue of Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (63 BC-14 AD), who became one of a triumvirate of rulers after the death in 44 BC of Julius Caesar, his great-uncle, whose dictatorship had brought an end to the Roman Republic. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

Prior to my election to office, I worked in the aerospace industry for 13 years. By 2010 though, many of the engineering offices I used to consult for had left California due to high taxes and burdensome regulations. As I termed out, my wife and I realized that both of her parents were suffering from dementia and would need our care. We made a go of it in our Southern California house for a year — but it was too cramped to accommodate four adults and two children. We made the move to Texas in late 2011.

I thought through the practical implications of moving back to California as I walked away from the Koi pond — that I would be so consumed with earning a living that I’d rarely have the time to even enjoy the literal or figurative fishponds, much less participate in public life.

Marcus Tullius Cicero paid the ultimate price for his decision not to retreat from the arena to the pond — soldiers loyal to his enemy, the would-be dictator Mark Antony, not only beheaded the politician, but they also cut off his hands for the crime of writing words against Antony’s tyrannical inclinations.

Today, service in the political arena rarely requires risk of literal life and limb — but it can require the moral courage to speak unwelcome truths and then move to convert truth to action.

Should we be blessed with the capacity, we must, as Teddy Roosevelt said, stand, "in the arena… strive valiantly… [and spend ourselves] in a worthy cause…"

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM CHUCK DeVORE

Chuck DeVore is a vice president with the Texas Public Policy Foundation, was elected to the California legislature, is a retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel, and the author of the new book, "Crisis of the House Never United."