'Serial' podcast challenged murder conviction but victim and her family get pushed aside

Had it not been for a media phenomenon 14 years later, Adnan Syed’s conviction for murdering Hae Min Lee would never have raised a single eyebrow. The evidence that led a jury to convict Woodlawn, Maryland’s Syed of killing his ex-girlfriend was rock solid. On the morning of her murder, a friend of Syed’s would testify that he secured a ride from Hae under false pretenses, telling her he needed a ride to pick up his car.

In fact, both his car and his cell phone were with Jay Wilds, his accomplice in the murder. Wilds would tell police how Syed strangled Hae in the secluded parking lot of a local Best Buy, the same parking lot where, in happier times, Syed and Hae would have romantic rendezvous.

Wilds, of course, was not entirely credible. His story changed, and he minimized his own involvement in the crime. But he was not the first person to reveal to the police what Syed had done. That had been Jennifer Pusateri, who had met Syed and Wilds in a mall parking lot the night of the murder. Wilds was understandably distressed, and Syed had barely left the scene when he spilled his guts.

AFFLUENT VIRGINIA HUSBAND AND NANNY CHARGED WITH MURDERS IN MANSION LOVE TRIANGLE

Pusateri, who had no reason to lie and whose story would remain consistent over time, would eventually go to the police with her mother and lawyer, telling all. Cell phone analysis would confirm Wilds’ and Pusateri’s story. When police pulled Syed’s cell phone records, they saw that the phone pinged over the Best Buy, the burial site and the car dump location the day and night of the murder.

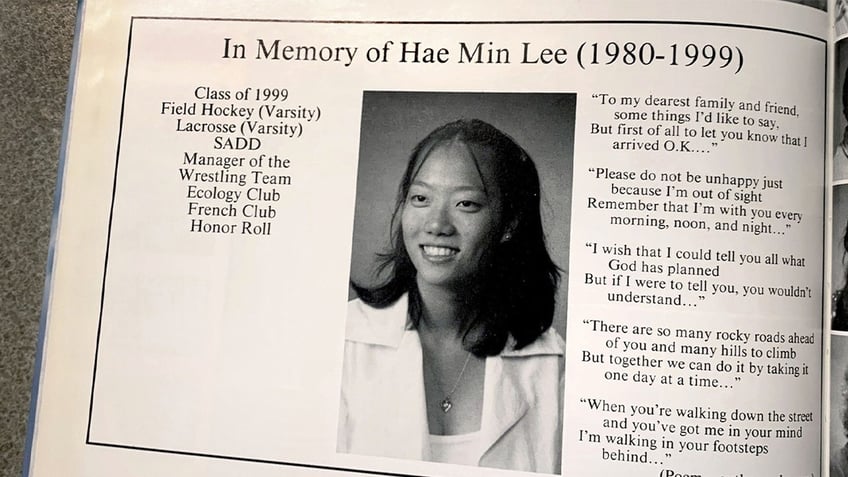

A tribute to Hae Min Lee, Class of 1999, in a Woodlawn High School yearbook. Lee was abducted and killed in 1999, and classmate Adnan Syed was convicted of her murder in 2000, but the case drags on. (Getty Images)

But that’s not all. Wilds would corroborate his story by leading the police to a piece of evidence they desperately needed — Hae’s abandoned vehicle. When the police searched the car, they found a map book in the back with the page for Leakin Park — the site of Hae’s burial — removed. Syed’s fingerprints were on the map book. Sitting on the map book was a single rose that had decayed over the weeks police had searched for the car. Syed’s fingerprints were found on the paper wrapping it, too.

The evidence suggests Syed had made one last effort to win back Hae, who had entered a serious relationship with a coworker only days before. When she refused, Syed strangled her. A broken turn signal bar on the steering column spoke to the violence with which Hae fought for her life. The motive for Hae’s murder was as tragic as it is disturbingly common — she rejected a man who would rather kill her than let her go.

Simple. Straightforward.

But then came "Serial."

The groundbreaking podcast that essentially created the true crime podcasting genre, Sarah Koenig’s engaging journalism combined with Adnan Syed’s guy-next-door charm won millions of listeners to Syed’s cause. "Serial" didn’t produce much in the way of new evidence, but it did generate copycats. Inspired either by a genuine belief in Syed’s innocence or a desire to recreate the "Serial" success, more podcasts, YouTubers, bloggers and an HBO documentary continued to advocate for Syed’s innocence. And yet despite Syed’s growing popularity, his legal situation remained unchanged. Over the years that followed, Syed would return to court many times, but each time, when the appeals were exhausted and the cases closed, Syed remained in prison.

Enter Marilyn Mosby.

In the summer of 2022, Mosby, the state’s attorney for Baltimore, had her own legal troubles. Earlier that year, a federal grand jury indicted Mosby on charges related to alleged COVID-19 fraud. Mosby needed a win, and Syed presented an opportunity.

Invoking a law allowing prosecutors to seek to vacate a conviction based on substantial evidence of innocence, Mosby flipped the state’s position on its head. After her office had defended Syed’s conviction for more than 20 years, Mosby was now advocating for Syed’s release.

Adnan Syed, center right, leaves the courthouse after a hearing on Sept. 19, 2022, in Baltimore. His conviction has been reinstated and the Maryland Supreme Court ordered the trial court to redo the hearing that had freed Syed. (Jerry Jackson/The Baltimore Sun via AP, File)

This was a shock, particularly to Hae’s brother, Young Lee. He begged the prosecutor for an opportunity to travel to Baltimore from California to attend a hearing on the vacatur motion. All he asked for was a week. However, this simple request was refused, despite Maryland’s liberal laws enshrining victims' rights.

It is difficult to overstate the depth of this betrayal. The prosecutor is the only voice victims and their families have. Our system is designed to protect defendants and to ensure that their rights are safeguarded. It makes little room for the victim. In the rare circumstance where overturning a conviction is required, shepherding the victim through the process is paramount. But here, Mosby turned her back on the Lees.

Why? It turned out that the entire vacatur process was a judicial farce. If Lee had been able to attend the hearing, he wouldn’t have seen much. The vacatur decision was made behind closed doors, during off-the-record, in-camera meetings with the judge.

Whatever it was that supposedly undermined the mountain of evidence against Syed was never presented in open court. No one was given the opportunity to challenge it or to cross-examine it, and the public was left in the dark about the merits of the motion. But the court did make sure to accommodate the pre-planned press conference on the steps of the courthouse that Syed and his team had planned for his post-release celebration.

Adnan Syed's mother Shamim Syed listens to Maryland State's Attorney for Baltimore Marilyn Mosby speak to the press after a judge overturned Syed's murder conviction and set him free pending a new trial during a hearing at the Baltimore City Circuit Courthouse in Baltimore, Maryland U.S., September 19, 2022. (REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst)

Young Lee, who had only been allowed to "attend" the hearing by Zoom, described how he and his family had been blindsided by the result. "This is not a podcast for me," he said. "This is real life — a never-ending nightmare for 20-plus years." But Lee didn’t give up. Instead, he fought for his sister.

Lee appealed the vacatur, claiming that his rights as a victim had been violated. And the courts, unimpressed by the sham proceeding, responded. An appeals court reversed the decision vacating Syed’s conviction, excoriating the process that led to it. The Maryland Supreme Court would go even further when the Court ruled on August 30. Not only would Lee get to attend a new hearing. He would get the opportunity to do something no one else had been allowed to do: challenge the vacatur on the merits, attacking the substance of the supposed evidence presented to justify Syed’s release.

Syed’s future is now in limbo. His conviction has been reinstated, and he is once again a convicted murderer. He remains out of prison as the courts and relevant authorities decide what exactly to do next.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

But his case has now become something bigger than a murder conviction, or even the media phenomenon that has circled it for the last decade. It is now a case about victims' rights and whether those rights can be steamrolled by a popular defendant with a sophisticated media apparatus behind him.

It is a case about a prosecutor willing to pervert justice for cheap PR points and a judge unwilling to take the time to actually test the evidence. And it is about a reverse-mob mentality that has grown in frequency across our country, where the masses, spurred on by podcasts, blogs, YouTube channels and 24-hour true crime coverage, demand an outcome based not on the evidence or the results of the judicial process, but on their own emotions and beliefs.

It took a jury two hours to find Adnan Syed guilty. It has taken 25 years and millions of dollars in media coverage to convince the majority of Americans that he is innocent. But guilt and innocence are not determined by a popularity contest, and the evidence of what happened that day in 1999 hasn’t changed.

None of the talk of Syed’s innocence, the revolution that "Serial" brought to the media landscape, or the political machinations of the prosecutor change the fact that Hae Min Lee, an 18-year-old with the world ahead of her, had her life stolen. And none of that changes the plain fact that Syed is responsible for her murder.

Invoking a law allowing prosecutors to seek to vacate a conviction based on substantial evidence of innocence, Mosby flipped the state’s position on its head. After her office had defended Syed’s conviction for more than 20 years, Mosby was now advocating for Syed’s release.

Soon, the state of Maryland will have a second chance to do the right thing. Mosby is gone, now a convicted felon, but she is appealing her conviction. The Maryland Supreme Court has ordered that a new judge, unconnected to the previous farce of a hearing, hear the case. And now, Young Lee will have the opportunity to challenge the evidence and argue that Syed should return to prison for his sister’s murder.

Here’s hoping that this time, the Baltimore state’s attorney and court system care more about justice for Hae Min Lee than what they’ll be saying on the next episode of "Serial."

Alice LaCour is co-host of the weekly true crime podcasts "The Prosecutors" and "The Prosecutors: Legal Briefs."

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM ALICE LACOUR

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM BRETT TALLEY

Brett Talley is co-host of the weekly true crime podcasts "The Prosecutors" and "The Prosecutors: Legal Briefs."