Capt. Sobel was called an incompetent leader, but he also drilled Easy Company into a stellar unit

Captain Herbert Sobel was both despised and admired by his own troops.

As commander of Easy Company, 506th PIR, 101st Airborne, the elite World War II paratroopers commonly known as the Band of Brothers, his legacy remains controversial.

Some veterans I’ve interviewed described Sobel as an incompetent leader with poor judgment, bound to get his own troops killed in battle.

BLACK MEDIC WHO TREATED HUNDREDS OF TROOPS UNDER ENEMY FIRE ON D-DAY TO BE HONORED IN ARLINGTON

Yet others described Sobel as a strategist. As a drill sergeant, he became integral in shaping the company into the best it could be, they insist.

Captain Herbert Sobel was the company commander of Easy Company, 506th PIR, 101st Airborne.

Sobel died in 1987 at age 75 — a staggering 17 years after shooting himself in the head in a botched suicide attempt. His wife and children likely didn’t hold a memorial service. But these parts of his life have not been portrayed accurately in the past.

In my bestselling book "WE WHO ARE ALIVE & REMAIN: Untold Stories from the Band of Brothers," I interviewed Michael Sobel, son of Herbert Sobel, and discovered the truth.

Herbert Maxwell Sobel was born on January 26, 1912, and grew up in Chicago. He attended the Culver Military Academy and excelled on his swim team. Of Jewish ancestry, Sobel grew to 6’ and bore a striking resemblance to actor David Schwimmer, who portrayed him in the HBO miniseries "Band of Brothers."

After graduating from the University of Illinois, and prior to Pearl Harbor, Sobel enlisted. He was tasked with leading Easy Company during basic training at Camp Toccoa, Georgia. He could be harsh as a drill sergeant, petty about discipline methods, and struggled with map reading, his men told me.

Not long before the invasion of Normandy, all the non-commissioned officers under his command resigned in protest of Sobel’s leadership, triggering his dismissal as company commander. Sobel subsequently led an airborne school in Chilton Foliat, England.

Following World War II, Sobel returned to Chicago and married an American nurse who’d served the allied effort in Italy. They had three boys. A daughter died several days after birth.

Sobel never talked about the war, Michael said. He stayed in the reserves for years, eventually retiring as a lieutenant colonel.

"He was a great father," Michael said. "He was loving and attentive. He doted on my mother and was very much in love with her. I never saw him lose his temper."

Captain Sobel with his young son. Photo courtesy the Sobel family via Rich Riley.

As years passed, and due to differing political beliefs, Michael grew apart from his father. After retiring from a managerial job for a phone company, Sobel attempted suicide. Michael recalled the evening he arrived home. He and his mother sat at the kitchen table trying to make sense of what had happened. She was inconsolable.

Sobel had shot himself in the head with a small caliber pistol. The bullet entered from the left temple and passed behind his eyes out the other side of his head, severing the optic nerves and leaving him blind.

"I don’t know why he chose to do what he did," Michael said. "I asked my mom, but she isn’t certain. She postulated that he thought he had cancer but was unwilling to get tested for the disease. He was not divorced from my mother yet, as some people suggest — that happened later."

After the suicide attempt, Sobel was moved to a VA assisted living in Waukegan, Illinois. He was fully ambulatory but sometimes in an unresponsive wakeful state, according to Michael. He had friends in the VA ward, though the living conditions at the VA were poor.

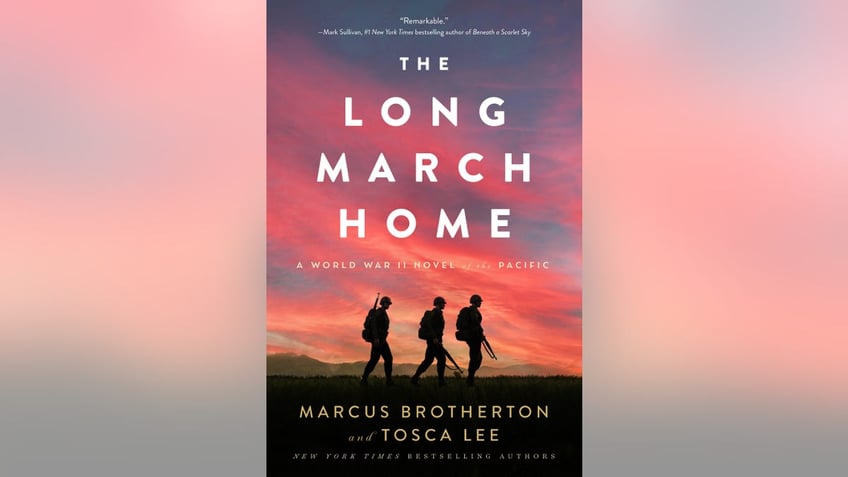

Marcus Brotherton's latest book, "The Long March Home," honors World War II veterans.

Michael confirmed that none of Sobel’s immediate family were in attendance when he died. To Michael’s knowledge, a memorial service was never held.

"Our contact with him had waned over the years," Michael said. "When he passed, we were unaware of the event. His sister attended to the details. It was days, perhaps even a week, after he died that his sister phoned my mom to let her know."

CLICK HERE FOR MORE FOX NEWS OPINION

The death certificate listed malnutrition as the cause.

The father and son didn't always get along. But they had patched up their differences.

The 3rd Platoon of the Band of Brothers. Photo courtesy the estate of Shifty Powers.

"One of the last times I saw him in the hospital I gave him a gold coin," Michael added, "a small memento of a trip to Guatemala I had been on, and some money for his personal needs. He received it well. I believe now, even in death, my father is closer to me than ever. I respect his strength and guidance. I’m thankful for the father I had."

In 2002, Michael attended a reunion of the Band of Brothers in Arizona.

A son of one of the Easy Company veterans hugged Michael through tears and said, "My father told me that if I ever had the honor of meeting you, to let you know that it was because of your father that I’m alive today."

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE BY MARCUS BROTHERTON

Marcus Brotherton writes extensively about veterans and World War II. His latest book, "The Long March Home," is a tribute to the WW2 troops who fought in the Pacific.