Abbey Ballentine, a student from Ohio’s Cleveland area, selected nearby Notre Dame College because it had everything she was looking for. It was a small, friendly campus with competitive Division II soccer and it was close to home.

By late fall of 2023, just a few months into her freshman year, she heard rumors the school had financial problems.

The official closure announcement was made early into the spring semester and the college closed its doors in May.

Campus advisors and administrators helped students quickly find other schools within a reasonable distance that would honor their financial aid packages and accept academic credits. Ballentine chose Thiel College in western Pennsylvania.

She’s still warming up to her new environment. The soccer team is Division III, a lower level than her prior team but also an opportunity for more playing time. The campus is more spread out and further from home. The move also pushed Ballentine out of her comfort zone and challenged her to switch majors from nursing to exercise science, which she has enjoyed.

“I think it’s a good match for me, and I actually like being further away from home, so far,” Ballentine told The Epoch Times. “But it’s only been a month, and I kind of still miss everything about Notre Dame.”

The support provided to Notre Dame College students in such a short window is rare, according to Rachel Burns, senior policy analyst with the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), a research and policy organization.

Burns said 70 percent of private college students who attended institutions that closed abruptly in the past five years received no help in finding a place to continue their academic career.

Of the 500,000 students displaced by closures, less than half re-enrolled elsewhere, she said.

And by this time next year, U.S. high school students could be looking at even fewer college choices.

Leaders at many higher learning institutions may determine their school’s fate in a matter of weeks after all federal financial aid checks for students attending this academic year are accounted for, says Gary Stocker of College Viability, a data analytics company that specializes in higher education finances.

“Many of them will decide, ‘I’m not sure we can survive past May,’” Stocker told the Epoch Times. “There’s a trend in short notice closures.”

Ninety-nine degree-granting institutions closed in the past year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. That includes community colleges, four-year schools, and universities. Seventeen of the schools were four-year nonprofit private schools, some of which had operated for more than a century before encountering severe financial problems in recent years.

Particularly impacted are small, private residential liberal arts colleges, where a typical student is in their late teens or early 20s and attends full-time and in-person.

Stocker said he expects that at least another 99 schools will announce their closures in the coming months. He estimates there are more than 2 million unfilled student slots across U.S. colleges and universities.

“It’s not even close to equilibrium,” Stocker said.

He said many factors are playing a role in shrinking enrollment numbers at traditional higher learning institutions, including the steep cost of tuition, job market trends, a recent Supreme Court decision, and even a sustained period of decreased birthrates across the country.

Factors such as last year’s delayed Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) rollout add to an already stressed market. Prospective students fill out a FAFSA form to find out their eligibility for financial aid, including grants, work-study programs, and loans. It can determine whether they can afford to attend college or not.

Drop in Students

U.S. college and university enrollment decreased by 1 million students over the past decade, according to data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

A slight increase in students enrolled in higher education classes between 2022 and 2023, mainly due to the spike in online course offerings and high schools that allow students to complete college-level credits, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Stocker called college closures a regional problem that has so far disproportionately affected campuses in the northeast, but it’s approaching the tipping point as a national epidemic.

The flurry of closures in New York could be a sign of things to come, he said.

Kieran Weinstein enrolled at the College of St. Rose in Albany, New York, in the fall of 2022. He was recruited to play on its Division II soccer team.

A year later, the school announced its final class would graduate in May 2024.

The sophomore from New Paltz, New York, decided to transfer out as soon as possible because he found the school environment to be depressing, and a number of courses in which he was interested had already been cut.

“I had professors crying, saying they didn’t know what they were going to do, and nearly every student was panicking trying to find a new school,” Weinstein said in an email to The Epoch Times. “As the school’s imminent shutdown was leaked first and not communicated directly by administrators, there was very little notice on how a potential teach-out program would work or any additional help. So, essentially, I had just a few weeks to find a new school on my own.”

Weinstein transferred to State University of New York (SUNY) Oneonta this fall. Other than his former soccer teammates and a few friends and professors, he said, “There’s very little I miss about St. Rose” because of the demoralizing situation he encountered there.

“The biggest difference, I would say, is the school having greater enrollment and more money makes the [Oneonta] campus feel much livelier and more vibrant,” he said.

The list of other private schools that closed this year in New York includes Wells College, Medaille University, St. John’s University’s Staten Island campus, and Long Island Business Institute.

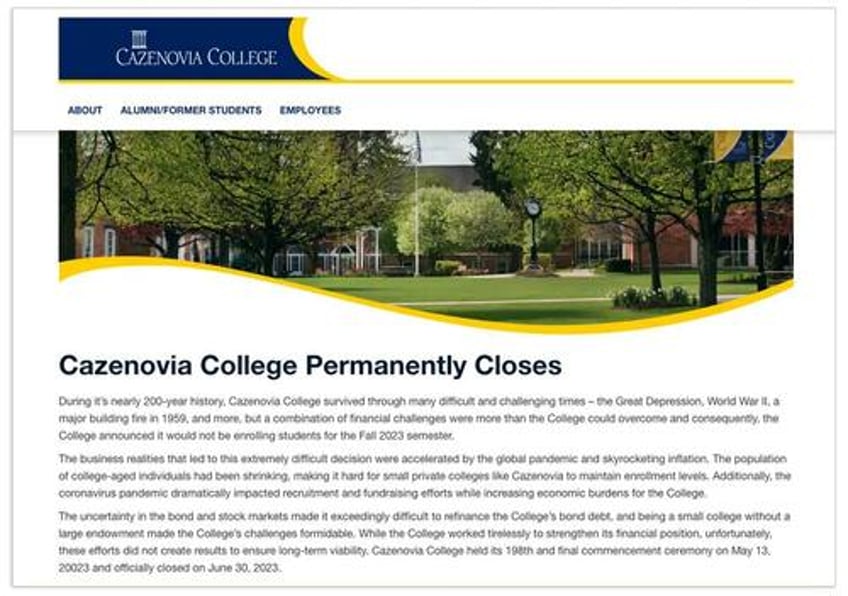

Cazenovia College, Alliance University, and Medaille University closed in 2023. Jamestown Business College is slated to close on Feb. 28, 2025, according to the New York State Education Department.

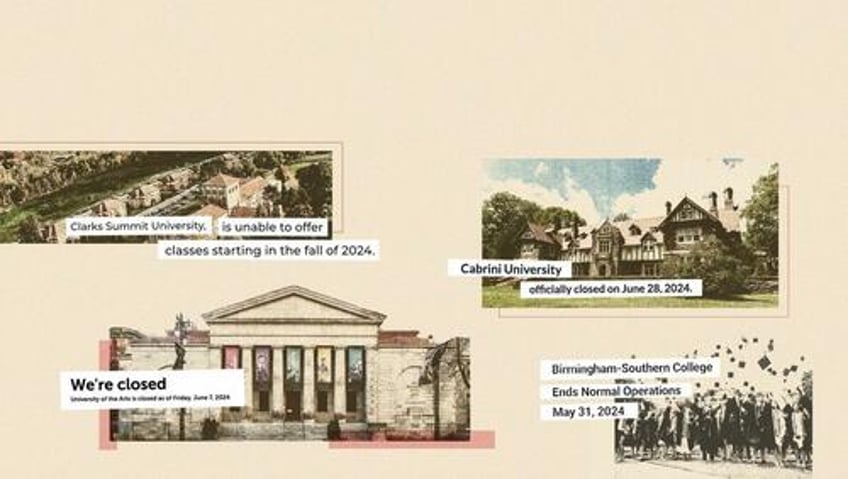

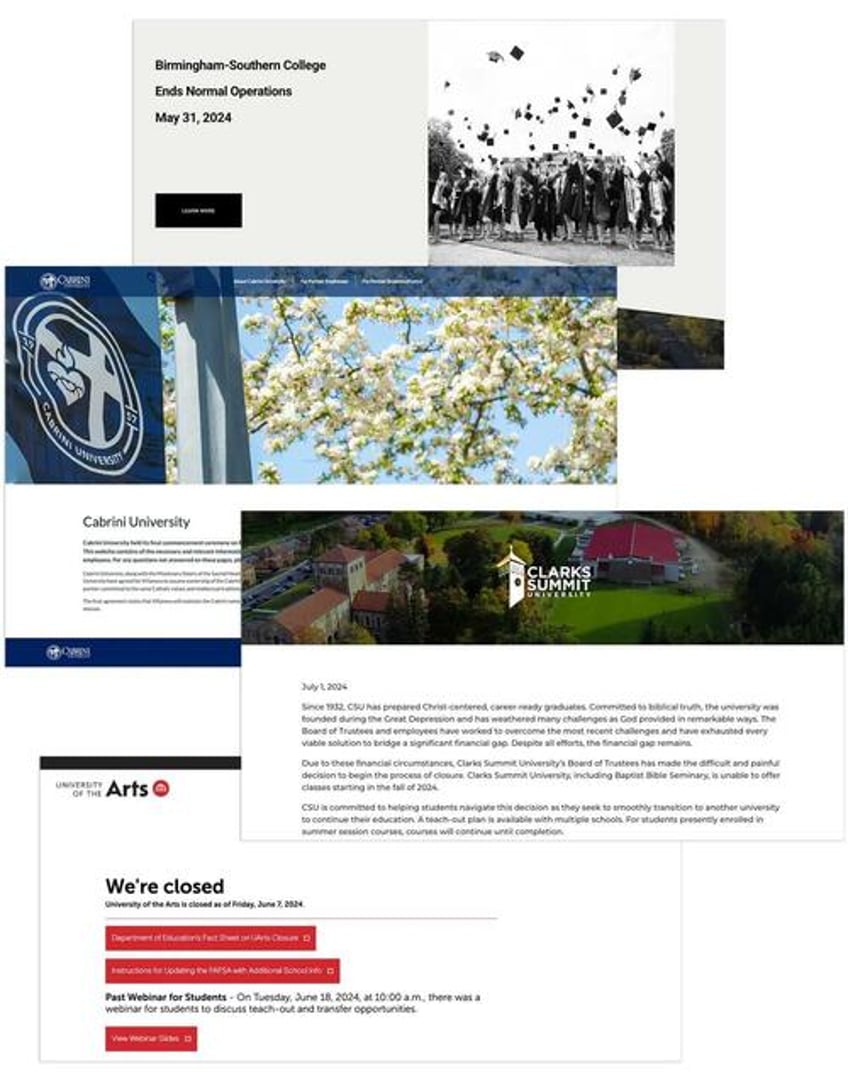

In other states, notable 2024 closings, aside from Notre Dame College in Ohio, include University of Saint Katherine in California, Birmingham-Southern College in Alabama, Lincoln Christian University in Illinois, and Hodges University in Florida.

In Pennsylvania, University of the Arts, Clarks Summit University, and Cabrini University all closed.

According to Emily Wadhwani, lead higher education analyst for Fitch Ratings credit rating agency, enrollments at most small private colleges and universities in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania have decreased because there aren’t enough students in a saturated higher-ed market where schools continually discount tuition rates to stay competitive.

While this appears to be a regional trend, she said, less competitive schools of all types nationwide are feeling the pinch.

Public colleges and universities in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Georgia, and Texas have cut or consolidated services to stay afloat, Wadhwani said.

She anticipates that regional campuses in Midwestern public university systems will usher in a new trend of financial problems and eventual closures for the same main reason: There are not enough students and tuition money to go around.

“These regional, directional campuses that are not the flagship schools have limited prospects of recovery,” Wadhwani said.

Looking Into Finances

The research Burns and SHEEO have conducted is based on surveys of 150,000 students across 500 private institutions in both the nonprofit and for-profit sectors.

She said more than 4,000 private schools or training programs closed between 2004 and 2020. Most of them were tuition-dependent and struggled with declining enrollments.

Although some schools communicate openly about the challenges they’re facing, “It’s tough to expect them to be transparent,” Burns said.

“States should do more to monitor them consistently” and push institutions to share their financial situation with prospective students and parents, she said.

Stocker, who builds data analysis apps for higher education consumers and institutions, said he’s bothered that schools don’t disclose their dire financial situations to prospective students and families who are preoccupied with price, location, major courses of study, and the campus environment.

“Most didn’t have the cultural and financial wherewithal to give their faculty, staff, and students enough notice,” Stocker said of the schools that closed earlier this year. “That’s really bothersome.”

He advises consumers to exercise due diligence, researching a school’s acceptance and graduation rates, enrollment numbers over a multi-year period, annual financial reports, staffing levels, and number of majors.

It’s also important to take a look at a school’s endowment, he said.

Endowments are used to lower sticker price tuition costs, fund capital projects, and assure the institution’s financial stability for more than one year at a time. When enrollment and subsequent tuition revenues decrease, schools have to dip into their endowments to cover operating costs. A sinking endowment may signal financial troubles.

Notre Dame College, which served about 1,400 students, had an endowment of $9.24 million in 2022, down by 31.6 percent from the prior year and not nearly enough to cover operating expenses for one year, according to Data USA’s school profile page.

Cazenovia College’s endowment was down to $3.84 million before school officials announced its closure. The College of St. Rose’s endowment was $40.1 million.

Delayed FAFSA Adds Stress

The college closure trend was exacerbated by last year’s delayed release of the FAFSA, said Wadhwani.

The revised FAFSA was expected to be released by October of 2023, but was delayed until December.

The delay affected $1.8 billion in student financial aid and particularly hurt small private schools that draw from low-income and minority student populations, Wadhwani said.

Some students awaiting aid delayed their enrollments or decided against college entirely, she said.

The ability for students to compare financial aid packages is crucial in the private school market, where the yearly cost of a higher education ranges from around $40,000 on the low end, to well over $80,000 on the high end.

Meanwhile, for the 2023–24 school year, the average cost of tuition at public colleges—which are funded by state tax dollars—was about $12,000 a year for in-state residents, and around $30,000 a year for out-of-state residents, according to the College Board.

A number of factors are hitting the private college market right now, Burns said. Among those, she cited tuition costs that are rising faster than financial aid amounts, and more young people who are unwilling to take on hefty student loans—particularly if those loans are high interest private loans rather than federal loans. In addition, she said, many high school graduates are going straight into the workforce or apprenticeships instead of college.

Nationwide, she added, the 2023 U.S. Supreme Court decision striking down affirmative action racial preferences in college admissions will cause minority enrollment at some schools to decline.

Moreover, starting Jan. 1, 2025. the U.S. Department of Labor will require employers to provide overtime wages to salaried employees paid less than $58,656 annually.

Increasing the overtime threshold again will potentially increase operating expenses across all types of higher education institutions that already struggle to make payroll.

Wadhwani said the change could affect adjunct professors, non-tenured instructors, and academic or athletic department office support staff—who are not considered hourly employees and often exceed 40 hours a week due to campus events on nights and weekends.

Nonetheless, many of the schools that have closed were financially underwater for years, Wadhwani told The Epoch Times.

Temporary campus closures and federal emergency aid during the COVID-19 pandemic masked their problems “before the Band-Aid was ripped off.”

The number of higher education bond impairments, or events where a school was unable to make a debt service payment, spiked from eight in 2009 to 17 last year, Fitch Ratings reported.

Small Colleges Adapt to Stay Afloat

In upstate New York, Colgate, Hamilton, and Vassar boast $1 billion-plus endowments, thanks to wealthy alumni donors and savvy investments.

But those elite institutions, which recruit nationally, are outnumbered by small, less competitive, cash-strapped liberal arts schools that compete for students who live within a half day’s drive from their campuses.

Some schools such as Hartwick College, located in Oneonta, New York, have adopted drastic measures to attract students.

Hartwick, with an acceptance rate of 69 percent and a graduation rate of 46 percent, saw its enrollment decline to 1,103 in 2022 from 1,503 a decade prior, according to NCES. Its endowment, meanwhile, was $65.1 million in 2022, a 16 percent decrease in 12 months, according to Data USA.

Earlier this month, school officials announced that in 2025-2026, the standard tuition rate will be dropped to $22,000, while room and board will cost $16,000, and students will be eligible for up to $10,000 in scholarships. By contrast, the school’s 2022 sticker price exceeded $50,000, though the “net price” calculated after financial aid awards came in at about $22,000, according to NCES.

In a Sept. 17 news release, Hartwick President James Mullen said the new pricing structure “provides clarity and transparency.”

“Our focus is on providing students with the tools they need to thrive academically, personally, and financially,” he said.

The Epoch Times reached out to Hartwick College.

Although some colleges have been criticized for keeping quiet about their financial troubles, others feel that being open is a more effective strategy.

Ithaca College, about 4 hours from New York City, has around 5,000 students and a 75 percent acceptance rate. The school has acknowledged its financial struggles in recent years. In a Sept. 4 news release, president La Jerne Terry Cornish said there will be no layoffs this year as school leaders manage a budget gap despite missing their enrollment target by about 200 first-year students.

The college intends to pursue an earlier and more intensive recruiting campaign this year, according to the release. In addition to the 200,000 high school upperclassmen who typically receive information about the college, Ithaca will reach out to 100,000 high school freshmen and sophomores, in order to build familiarity with the college “earlier in the high school journey.”

Ithaca broke even in 2023, and although it finished this past fiscal year with a $4 million deficit, that was nearly $10 million less than what administrators initially projected, Tim Downs, chief financial officer, said in the news release.

“As a campus, we’ve really held tight to what we needed to do, which is why we’ve been able to overachieve these deficits during these years,” he said. “And 2025 is no different.”