Hal Brands, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, has laid out in an essay in Foreign Affairs the key differences between what he rightly calls “American Globalism” and what has been called the “America First” approach to global affairs. Brands clearly is in the “American Globalist” camp, but unlike other supporters of the “liberal international order,” he does not label “America First” as isolationist. Instead, he lauds the global benefits to the post-1945 world order and worries that they will eventually disappear if Donald Trump regains the presidency. Brands doesn’t want the United States to be a “normal” country that only looks after its own national interests. What he fails to appreciate, however, is that the post-1945 world order he supports is already gone.

The geopolitics of 1945-1991 disappeared with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The war in Ukraine, despite the claims of many globalists, has not recreated the Soviet threat to Europe. If Ukraine, or parts of Ukraine, remain under Russian control, U.S. national security will not be endangered. Nor will Europe’s. NATO has doubled in size since 1991. Russia in relative power is considerably weaker than the Soviet Union was throughout the Cold War, and its ruling class no longer has a revolutionary ideology that legitimizes its continued rule and motivates international aggression. Of course, Russian imperialism has not disappeared from Russia’s foreign policy DNA, but the Russian empire of the Czars was never considered to be an existential threat to the United States (although the Monroe Doctrine included Russia in its restrictive warning), even when it occupied Alaska and parts of California in the 19th century. And today’s Russia is having difficulty holding on to the eastern provinces of Ukraine, and has once again sent out feelers for a ceasefire to end the war.

The architects of American foreign policy after the Second World War formed alliances and built-up U.S. military power to protect our national interests which were threatened by Stalin’s Soviet Union. They understood that American security depended on the geopolitical pluralism of Eurasia. Our policymakers at the time had read their Mackinder, Spykman, and Burnham. Brands has read them, too, and has written insightfully about their geopolitical wisdom. The geopolitical pluralism of Eurasia continues to be important to U.S. security, but the primary threat has shifted from Europe to the Indo-Pacific--from Russia to China. Those who Brands labels as “America Firsters,” including Donald Trump, have recognized this. Indeed, it was in the Trump administration that the real “pivot” to Asia began to occur, led by key national security officials like Elbridge Colby, Matthew Pottinger, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien. This shift was described in Josh Rogin’s magnificent book Chaos Under Heaven.

American Cold War foreign policy was not based on a selfless commitment to globalism. What Brands calls “American Globalism” was undertaken to protect U.S. national interests. Brands quotes Dean Acheson in 1952 to the effect that the post-World War II situation required the United States to broaden its view of our national interests. And so, it did. But the post-World War II world is gone. The Soviet threat that inspired our commitment to American Globalism is gone. It has been replaced by the Chinese threat which requires a shift in our commitments given the limits of American power.

The “American Globalism” supported by Brands fails to account for the limits of American power. Policymakers should continue to read Mackinder, Spykman and Burnham, but should also read Kennan and Lippmann who counseled prioritizing threats in the context of limited resources. Yet Brands still wants America to engage in democracy and human rights promotion and protect “intangible norms such as non-aggression.” He worries that a second Trump administration would “deglobalize” our defense, perhaps by withdrawing our nuclear umbrella from Europe and parts of Asia. He fears that Trump would no longer use American power to defend “distant states.” He expresses concern that Trump would not view our current alliances as “sacred.” He suggests that Trump would settle for a Western Hemispheric defense. He sides with the critics of “America First” who claim that a more restrained foreign policy “would be devastating to global stability.”

The “American Globalism” touted by Brands has not been an unvarnished success. It has made the nations of an entire continent content with resting their security on the United States and imposed an unnecessary burden on American taxpayers to provide for Europe’s common defense. It has led to an inconclusive war on the Korean peninsula that cost the lives of nearly 40,000 U.S. military personnel, a humiliating military defeat in Vietnam that cost the lives of nearly 60,000 U.S. military personnel, and more recent “endless wars” in Iraq and Afghanistan that resulted the deaths of more than 7,000 U.S. military personnel for no appreciable gain. It has led to the establishment of a national security state and what President Eisenhower called the “military-industrial complex” that impinges on the liberties of American citizens and profits from wars.

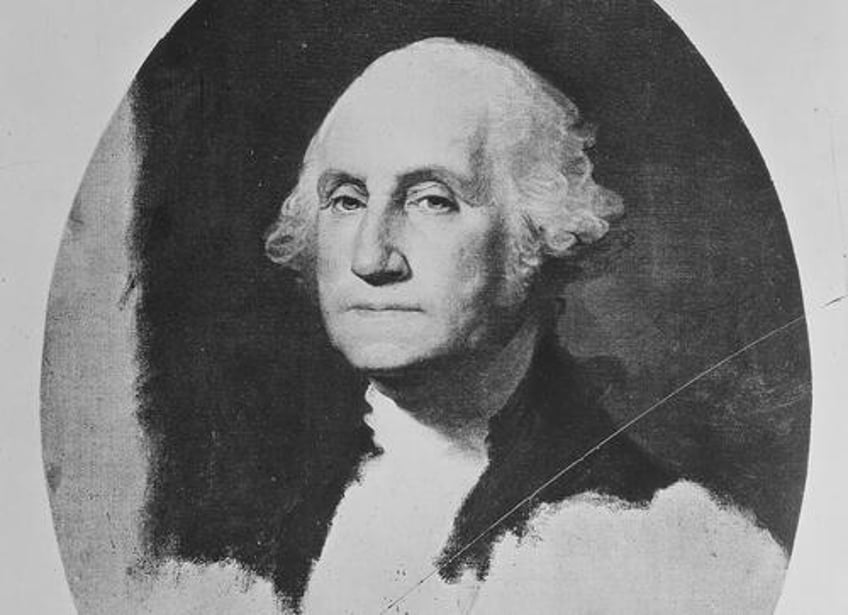

The American foreign policy tradition has much deeper roots that the post-Second World War order. It reaches back to George Washington and the wise counsel of his Farewell Address that warned against permanent alliances with, and passionate attachments to, other nations, while allowing for temporary alliances that serve our nation’s interests. Time and circumstances have not rendered the wisdom of Washington’s words obsolete.

Francis P. Sempa is the author of “Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century” and “America’s Global Role.” Francis is also writes the montly Best Defense column for RealClearDefense. Read his latest: Ukraine and the Pity of War.