To hear President Joe Biden tell it, the US economy is booming. Meanwhile, the Biden administration is running monthly budget deficits that you would normally see during a deep recession.

With two months left to go, the deficit for fiscal 2023 now stands at $1.61 trillion, after the federal government charted another massive shortfall in July.

And Biden wants to spend even more.

To put the $1.61 trillion deficit in perspective, prior to the pandemic, the US government had only run deficits over $1 trillion four times — all in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Trump almost hit the $1 trillion mark in 2019 and was on pace to run a trillion-dollar deficit prior to the pandemic. The economic catastrophe caused by the government’s response to COVID-19 gave policymakers an excuse to spend with no questions asked. Now the Biden administration has settled into the new status quo – running ’08 financial crisis-like deficits every single year.

The July budget deficit came in at $220.78 billion, according to the latest Month Treasury Statement. The shortfall was due to a double whammy of big spending and falling government tax receipts.

The Treasury collected $276.16 billion in July, a big drop from June’s $418 billion in revenue. That was slightly above July 2022 receipts, but the revenue trend in 2023 has generally been downward.

The federal government enjoyed a revenue windfall in fiscal 2022. According to a Tax Foundation analysis of Congressional Budget Office data, federal tax collections were up 21%. Tax collections also came in at a multi-decade high of 19.6% as a share of GDP. But CBO analysts warned it won’t last. And government tax revenue will decline even faster as the economy spins into a recession.

The bigger problem is on the spending side of the ledger.

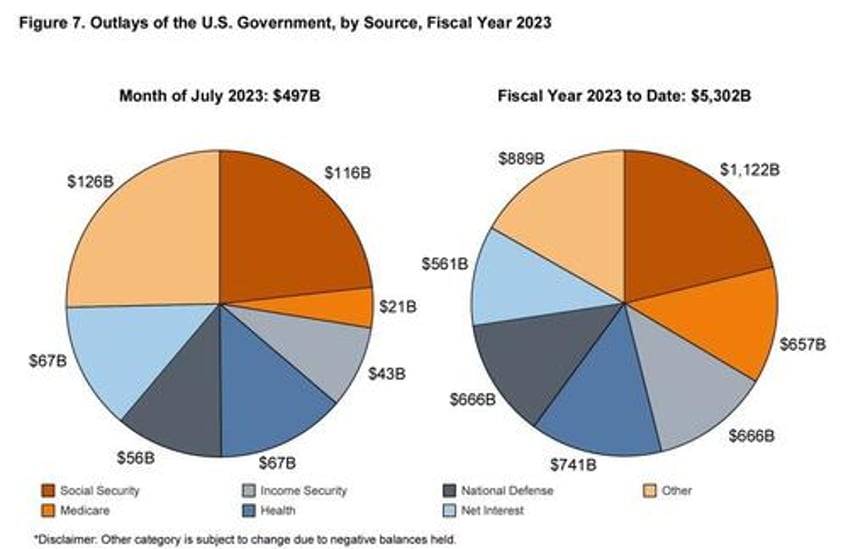

The Biden administration blew through another $496.94 billion in July. That was a 3.4% increase over July 2022 spending.

Now, you might be thinking that with the spending cuts in the Fiscal Responsibility Act, Congress fixed this problem. But we live in an upside-down world where spending cuts mean spending keeps going up.

In other words, the spending cuts will not put a dent in current spending levels. That means we can expect these massive deficits to continue month after month.

And the Biden administration already wants more money. Just last week, the president asked Congress to appropriate $40 billion in additional spending, including $24 billion for Ukraine and other international needs, $4 billion related to border security and $12 billion for disaster relief.

Keep in mind, the feds now have a credit card with no limit.

The fundamental issue wasn’t that the US government couldn’t borrow enough money. The fundamental problem was, and still is, that the US government spends too much money. Despite the pretend spending cuts, the debt ceiling deal didn’t address that problem. Even with the new plan in place, spending will go up. And it’s already historically high. That means big budget deficits will continue and the national debt will mount.

The US Treasury blew up the national debt by $850 billion in June alone as it scrambled to make up the ground it lost while the government was up against its borrowing limit. The national debt now stands at $32.66 trillion.

Meanwhile, according to the National Debt Clock, the debt-to-GDP ratio stands at 119.1%. Despite the lack of concern in the mainstream, debt has consequences. More government debt means less economic growth. Studies have shown that a debt-to-GDP ratio of over 90% retards economic growth by about 30%. This throws cold water on the conventional “spend now, worry about the debt later” mantra, along with the frequent claim that “we can grow ourselves out of the debt” now popular on both sides of the aisle in DC.

To put the debt into perspective, every American citizen would have to write a check for $97,547 in order to pay off the national debt.

This is an unsustainable trajectory, especially in a high-interest rate environment.

And if you believe the rhetoric coming out of the Federal Reserve, rates aren’t going down any time soon.

Meanwhile, the federal government has paid more than half a trillion dollars ($561 billion) on interest payments alone in fiscal 2023. In July, Uncle Sam forked out $67 billion in interest payments. The only spending categories that were larger were Social Security and Medicare. Last month, the US government spent more on interest expenses than it did on national defense.

According to an analysis by the New York Times, net interest costs rose by 41% last year. The Peterson Foundation said the jump in interest expense was larger than the biggest increase in interest costs in any single fiscal year, dating back to 1962.

The cost of financing the debt will almost certainly rise even more now that Congress has done away with the debt ceiling for two years.

As the Treasury floods the market with new debt, bond prices will likely fall in order to create enough demand for all of those Treasuries. Bond yields are inversely correlated with bond prices, and as prices fall, interest rates rise.

We’re already seeing extreme weakness in the bond market. Financial analyst Jim Grant recently said we could be heading toward a generational bear market in bonds. This would mean rising interest rates for the US government even if the Fed stepped in and tried to push rates down. This is an unsustainable trajectory for the US government. It simply cannot continue to borrow at this pace in a high-interest rate environment.

In fact, if interest rates remain elevated or continue to rise, interest expenses could climb rapidly into the top three federal expenses. (You can read a more in-depth analysis of the national debt HERE.)

It’s easy to blame the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes for this problem, but the real problem started with more than a decade of artificially low interest rates and easy money. This incentivized borrowing. The federal government’s rising interest expense is just one example of the debt chickens coming home to roost. And it’s one of the reasons Peter Schiff says the Fed will never get price inflation back to its 2% target.