On June 6, 1984, the 40th anniversary of D-Day, President Ronald Reagan and a crowd of veterans, now senior citizens, watched sixty-something-year old Ranger veteran Herman Stein, along with a dozen Green Berets decades younger, re-enact the most difficult mission of D-Day: scaling the 90-foot cliffs of Pointe du Hoc, France to take out the German machine guns targeted on the beach. Climbing hand-over-hand, the sexagenarian easily reached the top ahead of the younger men. “All these younger guys will be all right if they just stick with it. They hug the cliff too much,” he joked.

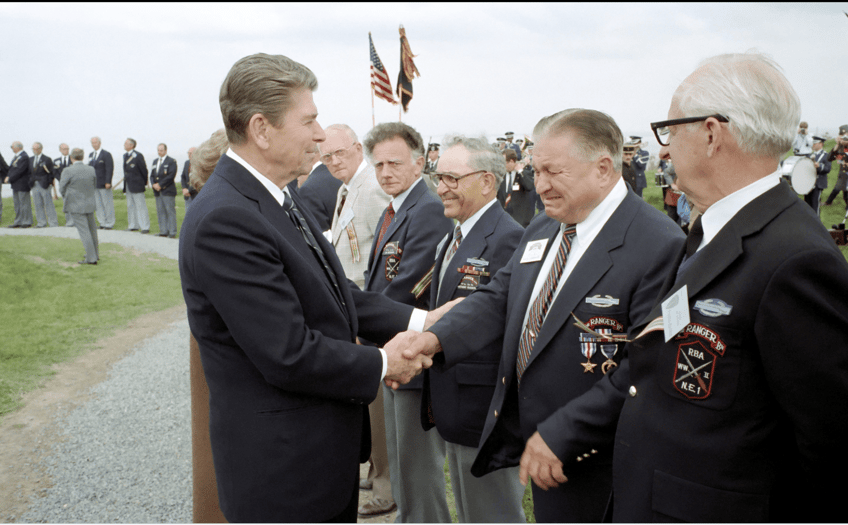

Ronald Reagan Giving a Speech on the 40th Anniversary of D-Day, White House Photographic Collection

In 1944, the Allied plans had called for 225 Rangers, including Dog Company, to land on a tiny beach, scale the ten-story-high cliffs under a torrent of enemy fire, and destroy the most dangerous gun battery threatening the American portion of the invasion.

It was a suicide mission.

Allied headquarters projected Ranger casualties would top seventy percent. One intelligence officer remarked, “It can’t be done. Three old women with brooms could keep the Rangers from climbing that cliff.” In fact, only about 90 of the 225 would succeed.

Atop Pointe du Hoc, the Germans had constructed a massive fortress. They considered the position largely impregnable from a seaborne attack, thanks to the ninety-foot cliffs. Nevertheless, they had placed artillery shells suspended by wires—precursors to today’s IEDs (improvised explosive devices)—along the cliff faces as an added defense against a seaborne assault. German machine guns and anti-aircraft guns could also hit the beach at the base of the cliffs, where any attacking craft would be forced to land. The fortifications made land-borne and parachute attacks similarly difficult: heavy minefields, machine gun nests, bunkers, and barbed wire rendered an overland attack without armor practically impossible. The only possible Allied route of attack was a frontal assault.

Pointe du Hoc, Public Domain

Pointe du Hoc’s formidable defenses guarded six 155 artillery pieces with a potential range of 25,000 yards (14 miles) trained on the American landing beaches. Destroying them would be “the most dangerous mission of D-Day,” and it was critical to the success of the invasion.

On June 6, 1944, around 7:15 a.m., the Rangers disgorged from their landing craft, many into water over their heads as they made their way to the rocky beach at the base of the cliffs. From the top of the cliff, the German soldiers relentlessly fired on the incoming Americans. Capable of firing between 1200 and 1500 rounds per minute, the MG-42s struck the gravel around the Rangers. “I thought I was kicking up pebbles and dirt. But they were actually bullets that were hitting the sand and kicking up the dirt around me,” one Ranger remembered.

Some of the men, like Sigurd Sundby from Dog Company, struggled with the ascent. “The rope was wet and kind of muddy; my hands just couldn’t hold. They were like grease, and I came sliding back down. I wrapped my foot around the rope and slowed myself up as much as I could, but my hands still burned.”

U.S. Rangers Scale Cliff to Climb Pointe du Hoc on D-Day, Public Domain

First Sergeant Leonard Lomell, Dog Company’s senior enlisted man, took a machine gun bullet in his side, but continued to ascend. Adrenaline coursed through his body, allowing him to ignore the searing pain.

Climbing next to the first sergeant was 2nd Platoon’s radio operator, Sergeant Robert Fruhling. Lomell could hear the ominous sound of crumbling rock as the face of the cliff gave way with each foothold. Running out of strength from making the treacherous hand-over-hand ascent while avoiding enemy fire, the wounded Lomell strained to lift his body the last few feet. When at last he crested Pointe du Hoc, he looked down and spotted Fruhling, who was now near the summit, but barely hanging on. Fruhling cried out for help.

Unable to reach the radioman, Lomell provided covering fire from his Thompson and shouted, “Hold on. I can’t help you!” Lomell spotted Sergeant Leonard Rubin and called out for him to help the struggling Ranger. Just as Fruhling was slipping down the rope, Rubin grabbed him by the nape of his neck and, with a mighty swing, hoisted him over the top of the Pointe.

Soldiers Resting on Pointe du Hoc on D-Day

Lomell and his men fought through a maze of bunkers atop the Pointe but found that the guns they had come to destroy were not in their casements. Acting on their own initiative, Lomell and Sgt. Jack Kuhn found tire tracks made by the German guns and followed them. After fighting through several German strongpoints,they located five of the guns in an apple orchard hidden under camouflage netting.Using their thermite grenades,t hey disabled the deadly weapons, two men accomplishing a mission that hundreds of Allied bombers and scores of heavy naval guns of Allied warships failed to achieve.

The surviving Rangers then tackled their secondary mission. They set up a roadblock across the road atop the Pointe that connected Omaha and Utah Beaches. On the night of June 6-7, hundreds of Germans counterattacked in force, overrunning portions of the Ranger position and nearly retaking the Pointe in an epic assault. But the Rangers held. Eventually, they linked up with troops who had fought their way off Omaha Beach. Through personal initiative and courage, a small group of men proved that they could shape history.

Most of the Rangers in this article were my close friends. Only a few heroes of Dog Company remain. Unlike the counterfeit heroes of Hollywood and current pop culture who incessantly crave attention for faux achievements and insignificant acts, this WWII generation of American rock stars is quietly fading before our eyes.

We are living through some of the most dangerous times in history; as one historian put it the ‘past is present.’ Courage remains a priceless commodity. Like at Pointe Du Hoc where a small group of Americans rose to the moment to shape history and destiny, we stand at the edge of a precipice. We need a new generation to defend American liberty. Will they be up to the challenge and follow in the footsteps of these heroes? Let’s hope so.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically-acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He has interviewed more than 4,000 WWII veterans and is the author of thirteen books, including his new bestselling book on the Civil War The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations, currently in the front display of Barnes and Noble stores nationwide. His other bestsellers include: Dog Company, The Indispensables, The Unknowns, and Washington’s Immortals. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and often speaks on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickKODonnell.com @combathistorian