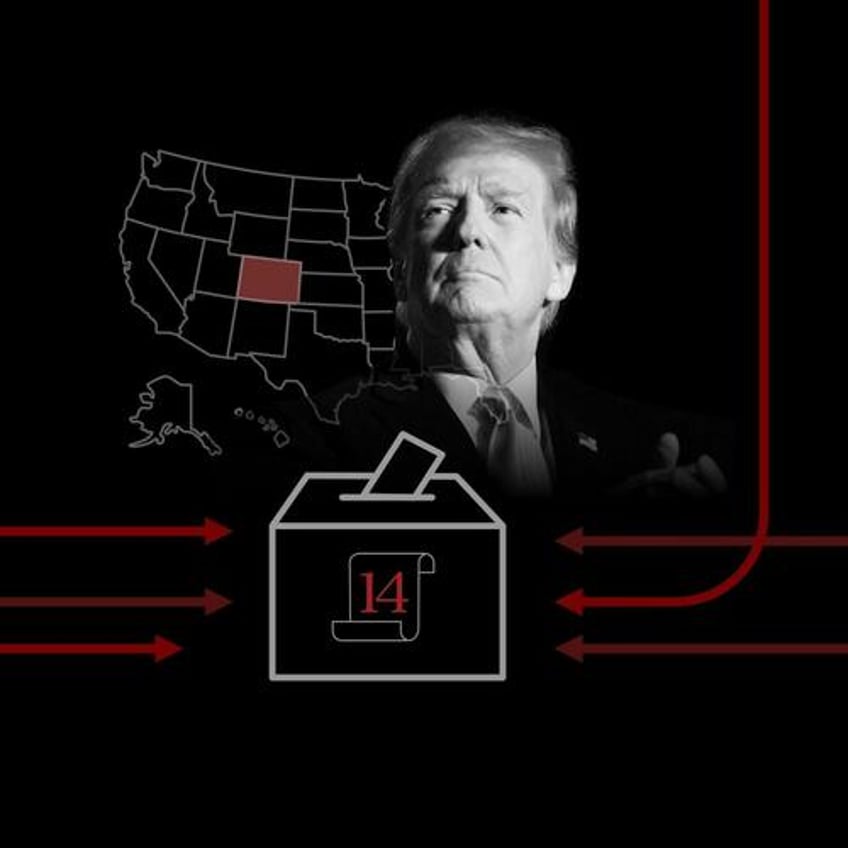

Today, at 10amET, the Supreme Court will rule on Colorado’s efforts to get former President Trump off the 2024 ballot for “insurrection or rebellion”.

A Wall Street Journal editorial calls for a 9-0 vote to strike it down.

Additionally, as RaboBank's Michael Every notes, within days we may then see how the Supreme Court feels about the D.C. appeals court ruling over Trump’s January 6 court case, which struck down his claim to immunity: as the Journal op-eds separately, while Trump’s defence is “legal sophistry… the sweeping nature of the ruling means that it also risks weakening the office of the Presidency, so perhaps at least four Supreme Court Justices will be interested in having the last word.”

In short, more twists and turns to come(?)

But, this morning, all eyes and ears will be focused on whether Democracy is in danger from a decision by SCOTUS and Jonathan Turley - the Shapiro Professor of Public Interest Law at George Washington University - will be providing live coverage of the Supreme Court arguments.

When I am not on air, I will be doing my usual running analysis on Twitter/X.

...The Court has long struggled with the aftermath of that decision and does not relish the chance to again enter the fray of a close presidential election. https://t.co/OATI29AFoT

— Jonathan Turley (@JonathanTurley) February 8, 2024

I have been a vocal critic of the theory under Section 3 as textually and historical flawed.

It is also, in my view, a dangerously anti-democratic theory that would introduce an instability in our system, which has been the most stable and successful constitutional system in the world.

You will be hearing arguments from:

Jonathan Mitchell, who is representing Trump. He is a Texas lawyer who has previously argued before the Court.

Jason Murray, who is representing Republican voters who want to disqualify Trump. Murray clerked for Justice Elena Kagan and also then judge Neil Gorsuch on the Tenth Circuit.

Shannon Stevenson, who is the Colorado Solicitor General. Stevenson only recently became solicitor general and was previously in private practice.

We can expect the justices to focus on the three main questions before the Court:

1. Is the president “an officer of the United States” for purposes of section 3?

2. Is section 3 self-executing?

3. Was January 6th an “insurrection” under Section 3.

You will likely hear references to Griffin’s Case in the arguments. Not long after ratification in 1869, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase ruled in a circuit opinion that the clause was not self-executing. He suggested that allowing Congress to simply bar political opponents from office would be a form of punishment without due process and would likely violate the prohibition on bills of attainder.

You will also likely hear comparisons to other sections and how this case could impact the meaning of terms like “officers” and “offices.” For example, the Appointments Clause gives a president the power to “appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States.” That creates a tension with defining, as do those pushing this theory, that a president is also an officer of the United States. Most of the advocates simply argue that the meaning is different.

You may also hear references to the Incompatibility Clause which provides, “no Person holding any Office under the United States, shall be a Member of either House during his Continuance in Office.” U.S. Const. Art. I, § 6. Critics have noted that the proponents of this theory argue that the Speaker and Senate President Pro Tempore are “Officers of the United States.” Indeed, they reject any difference between an “Officer of the United States” and an “Office under the United States.”

However, this creates tension with members serving as Speakers and Senate Presidents Pro Tempore since those positions are also “Offices under the United States.”

Some of the argument will clearly focus on the history and context for this amendment.

These members and activists have latched upon the long-dormant provision in Section 3 of the 14th Amendment — the “disqualification clause” — which was written after the 39th Congress convened in December 1865 and many members were shocked to see Alexander Stephens, the Confederate vice president, waiting to take a seat with an array of other former Confederate senators and military officers.

Justice Edwin Reade of the North Carolina Supreme Court later explained, “[t]he idea [was] that one who had taken an oath to support the Constitution and violated it, ought to be excluded from taking it again.”

So, members drafted a provision that declared that “No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof.”

Jan. 6 was a national tragedy. I publicly condemned President Trump’s speech that day while it was being given — and I denounced the riot as a “constitutional desecration.” However, it has not been treated legally as an insurrection. Those charged for their role in the attack that day are largely facing trespass and other less serious charges — rather than insurrection or sedition. While the FBI launched a massive national investigation, it did not find evidence of an insurrection. While a few were charged with seditious conspiracy, no one was charged with insurrection. Trump has never been charge with either incitement or insurrection.

The clause was created in reference to a real Civil War in which over 750,000 people died in combat. The confederacy formed a government, an army, a currency, and carried out diplomatic missions.

Conversely, in my view, Jan. 6 was a protest that became a riot.