One hundred years ago on May 26, American voters pressured Congress in 1924 to end the Ellis Island wave of migration and to reduce the inflow of new immigrants.

The law is being lamented by David Bier, an advocate from the Cato Institute, which is funded by investors who oppose borders, non-market solidarity, and other populist curbs on their businesses and stock portfolios:

It is plausible that the United States would be twice its [population] size today if immigration had continued. The United States would not have lost nearly as much diplomatic, social, and market influence to China and other countries in recent years if its economy and consumer base were twice as large as they are now. The larger population would mean a larger economy and more production of goods and services to benefit all Americans.

The 1924 law was signed on May 26 by President Calvin Coolidge, and it ended the Ellis Island wave of easy migration.

Arrivals dropped by two-thirds, from 70o,000 in 1924 down to an annual average of 200,000 from 1926 to 1970. That inflow added just one migrant for every 12 births in 1939 — which is far below President Joe Biden’s policy of adding roughly one migrant for every U.S. birth. By 1970, migrants comprised just 5 percent of the U.S. population — far below the 15 percent seen in 1910 and again in 2024.

The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 was sidelined 41 years later when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

That 1965 law is now quickly transforming the United States’ population, society, and economy, amid much public debate over Biden’s mass immigration and President Donald Trump’s promises of reform in 2025.

Rear view of an immigrant family on Ellis Island looking across New York Harbor at the Statue of Liberty, 1930s. (Photo by FPG/Getty Images)

Today’s economic-minded critics of the 1924 law are politically powerful, partly because Biden’s inflow of immigrant workers, consumers, and renters spins off a huge wealth to fund pro-migration advocacy, lobbying, and political campaigns.

Much of the advocacy funding goes through the various ethnic groups who understandably want to bring more of their home-country demographic. Even more, cash goes to the investor-adjacent progressives who viscerally resent the international borders that curb their ambitions to level every demographic group in the world. Progressives describe U.S. borders as racist — regardless of the United States’ multiracial population — because they hinder the hopes and ambitions of racially diverse people outside the United States.

Pro-migration advocates are now trying to combine both economic and racial claims as they denounce the 1924 law. “Today, we face conditions eerily similar to those leading up to the 1924 law,” said Zeke Hernandez, a pro-migration professor at the Wharton School. He wrote in the TheHill.com:

100 years ago today, America committed its biggest immigration blunder when President Calvin Coolidge signed the National Origins Act. As we commemorate the anniversary, most of the conversation focuses on condemning the racist motivation of excluding Asians and Southern and Eastern Europeans. (Suffice it to say that Adolf Hitler was a fan.)

…

This time, we’ve experienced a mass arrival of Asians and Latin Americans. Like 100 years ago, many today worry that they’re poor, uneducated, don’t speak English and bring unassimilable cultures and religions. The combination of 9/11 and a leaky border now provide a national security pretext for draconian restrictions, as WWI did back then. And a group of politically motivated and well-funded pundits are making the same old “villain” argument that immigrants hurt us economically and threaten our precious heritage.

But Roy Beck, former head of the NumbersUSA reform group, has a more optimistic view of the 1924 law:

Every social group in the south gained economically as labor shortages for investors and farm companies to buy machinery that allowed locals to do more — and to earn more — each day. “Cotton was still overwhelmingly picked by hand in 1960. By 1964, 42 percent of the cotton harvest was mechanized; five years later, the share had reached 82 percent,” a labor economist noted in 2017.Ironically, this 1924 migration law had been opposed by the southern establishment that relied on labor, not machines. For example, a pro-migration 1905 article celebrated that:All classes and ethnicities of American workers benefitted. But Black workers’ status soared nearly twice as fast once expanding industrial opportunities allowed them to prove their productivity. Between 1940 and 1980, for example, the real incomes of Black men rose four-fold. More than 70% of Black Americans were found to belong in the middle class by 1980, up from 22% in 1940. Combined, lower rates of migration and lower fertility caused around one-third of a great reduction in U.S. inequality during those decades, according to economic historians Jeffrey G. Williamson and Peter H. Lindert.

No wonder W.E.B. DuBois observed, in the NAACP magazine Crisis, that the 1924 legislation’s “stopping…the importing of cheap White labor on any terms has been the economic salvation of American Black labor.”That “economic salvation” could have arrived decades earlier, if Congress had simply ended mass immigration. Williamson and economist Timothy J. Hatton calculated that, without foreign immigration from 1890 to 1910, real wages for urban workers could’ve been 34% higher in 1910.

In Wilmington, where the negro laborers have proven so unreliable, the preference for north Europeans has given way before necessity, and Italians are being brought in to furnish more efficient labor. Texas has secured colonies of northerners, of Germans and of Italians, and smaller numbers of Japanese rice farmers.

The labor shortage fuelled a wave of machine-driven productivity, automation, professionalism, and wartime scientific research, to create a massive wave of 1950s and 1960s prosperity across America. The prosperity in turn birthed the Baby Boom generation which is still riding that prosperity into a wealthy retirement as their less fortunate grandchildren live with disappointing wages and wealth-sucking mortgages.

The slowdown in migration also allowed American society to digest the diversity of 25 million migrants that had been imported during the Ellis Island era, Mark Krikorian at the Center for Immigration Studies wrote for the New York Post:

The pause from 1924 to 1965] in immigration led to a half-century-long decline in the foreign-born share of the population, from a level that fluctuated between 13% and 15% of the nation’s inhabitants during the Great Wave, to a low of less than 5% in 1970.

Immigrant communities were thus not continually refreshed with newcomers; that, combined with vigorous and self-confident Americanization efforts in schools and elsewhere, forged the strong common national identity that helped America prevail over Nazism and Communism.

The post-1924 gain for ordinary Americans would be reversed by the 1965 law, Princeton University economist Leah Boustan wrote in her 2017 book, Competition in the Promised Land: Black Migrants in Northern Cities and Labor Markets. Economists “estimate that immigrant arrivals can account for one-third of the declining wages of black high-school dropouts from 1950 to 2000,” Boustan wrote. By 1980, the flood of foreign migrants was sending black Americans back to southern cities.

Since 1970, when the new immigrants allowed by the 1965 act began to arrive, employees have seen an irregular decline in their share of the new wealth produced every year, according to federal data displayed by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The employees’ share of the U.S. economy dropped from almost 52 percent in 1970 down to 43 percent in President Joe Biden’s high-migration economy. That drop moved 9 percent of the economy — roughly $1.5 trillion in 2022 — from 160 million employees to their employers, investors, and government.

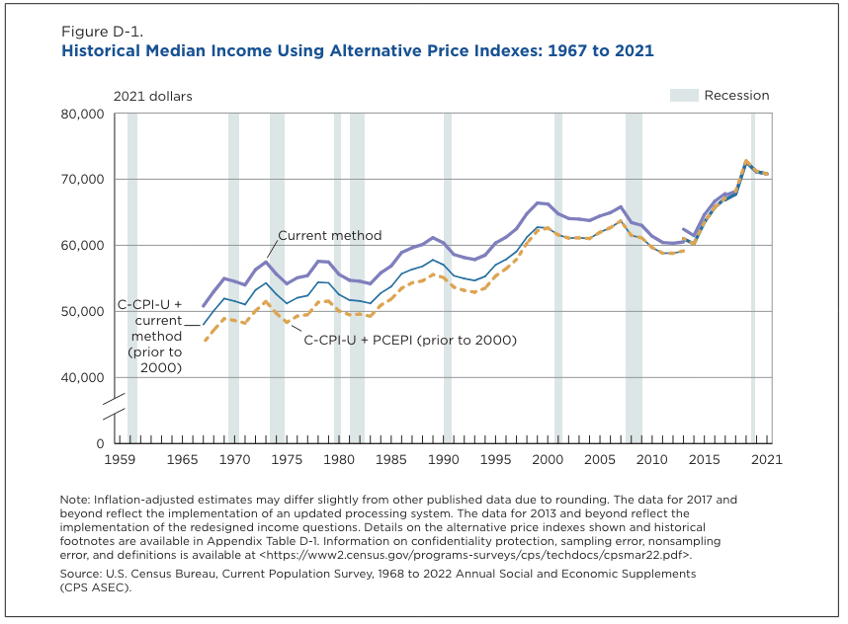

Similarly, a 2023 report by the Census Bureau showed that median income climbed from $55,000 in 1970 to an inflation-adjusted $60,000 in 2015 amid the massive inflow enabled by the 1965 law and the subsequent 1990 immigration law. That rise is just 9 percent over 45 years, or 0.2 percent per year.

The 1990 law roughly doubled the annual inflow of immigrants and allowed companies to hire foreign graduates via the H-1B program for jobs sought by American graduates. The 1990 migration law also established the informal policy of Extraction Migration, which imports millions of consumers, renters, and workers to compensate for Wall Street’s export of the nation’s high-productivity manufacturing sector and white-collar jobs to the citizens of low-wage developing nations.

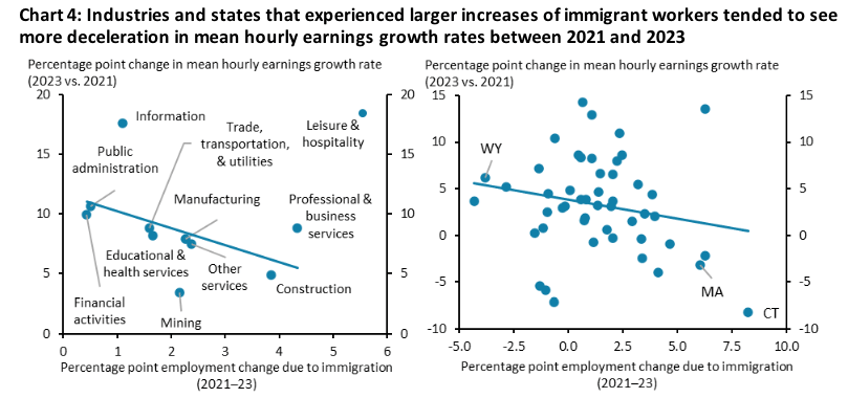

Since 2021, average income has been pushed down by Biden’s massive inflow, according to a May 22 bulletin from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. In the home state of Sen. Chris Murphy (DCT), for example, wages fell by roughly 8 percent amid an 8 percent rise in employment due to immigration, the report showed.

Today’s supporters of the 1924 law take care to criticize the ethnic politics that were commingled with civic and economic arguments during the 2024 debate.

The politics were sketched by former professor and author Hasia Diner to JTA.org in April 2024:

There [were] multiple forces at work. First, … the white, Protestant, Anglo-Saxon [Americans]— were really disturbed by World War I. Ethnic groups were lining up with their home countries [during the war], so everybody wants their voice to be heard, based on what they thought was good for their ancestral home. And just as the Austro-Hungarian empire was breaking up [into multiple countries after the war], many “Americans” really feared that the United States was becoming balkanized in the same way. I think of the 1924 act as an effort to end that process of balkanization.

…

Antisemitism certainly ratchets up in the 1920s and the 1930s, when you have Henry Ford and America First. But again, every opinion poll done after 1935 shows that the American public does not want immigration, period.

The law barred millions of migrants during the 41 years, including Jews subsequently killed by Adolf Hitler’s Nazis in 1942 and 1943. “Between 1938 and 1941, 123,868 self-identified Jewish refugees immigrated to the United States,” according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Many hundreds of thousands more had applied at American consulates in Europe, but were unable to immigrate. Many of them were trapped in Nazi-occupied territory and murdered in the Holocaust.

Some of the leading advocates of the 1924 law denied racial hostility. “It makes no difference from whence they come — too many come,” said Rep. Albert Johnson (R-Wash).

But the taint of ethnic politics helped opponents kill the 1924 law in 1965, said Beck:

Its system of national quotas favoring northern Europeans and fully excluding many countries on other continents came to be seen as at odds with the nation’s move toward a race-blind society. The desire to correct this racial discrimination inspired Congress to pass new immigration legislation in 1965 that inadvertently re-started the mass immigration of today — which none of the 1965 law’s sponsors said they intended …

The Immigration Act of 1924 fumbled on who should immigrate. But in deciding how many should, the law enabled descendants of American slavery to prove that — despite racist domestic laws and social mores that still remained in place — they could prosper in tight labor markets even faster than white workers.

“We need to do something similar today,” Krikorian told Breitbart News. “But without the natural origins baloney and by simply reducing [immigration] numbers.”

Unsurprisingly, today’s advocates for more migration are eager to wrap the ethnic politics of the 1924 law around President Donald Trump and other advocates of immigration reform. “We find ourselves facing the same precipice our forebears did exactly 100 years ago,” Hernandez wrote in TheHill.com. “Will we be smarter this time?”

Larry Fink, founder of the $10 trillion BlackRock investment firm, is asking the same question. “I can argue, in the developed countries, the big [economic] winners are the countries that have shrinking populations,” Fink said last month:

That’s something that most people never talked about. We always used to think [a] shrinking population is a cause for negative [economic] growth. But in my conversations with the leadership of these large, developed countries [such as China, and Japan] that have xenophobic anti-immigration policies, they don’t allow anybody to come in — [so they have] shrinking demographics — these countries will rapidly develop robotics and AI and technology …

“If a promise of all that transforms productivity, which most of us think it will [emphasis added] — we’ll be able to elevate the standard living in countries, the standard of living for individuals, even with shrinking populations,” Fink said.