WEIRTON, West Virginia - Most people in this town will tell you they’d rather have taken a physical punch to the gut than get the news they received yesterday when Cleveland-Cliffs Steel announced it was idling its tinplate production plant, a move that directly cost 900 people their jobs.

It isn’t just those workers who face catastrophic uncertainty; this closure also jeopardizes the jobs of thousands more people whose businesses supported the plant: the barber shops, gas stations, mom-and-pop grocery stores, the machine shops that make the widgets for the steel industry. And there’s also the demise of the tax base, which affects the school district and the quality of the roads.

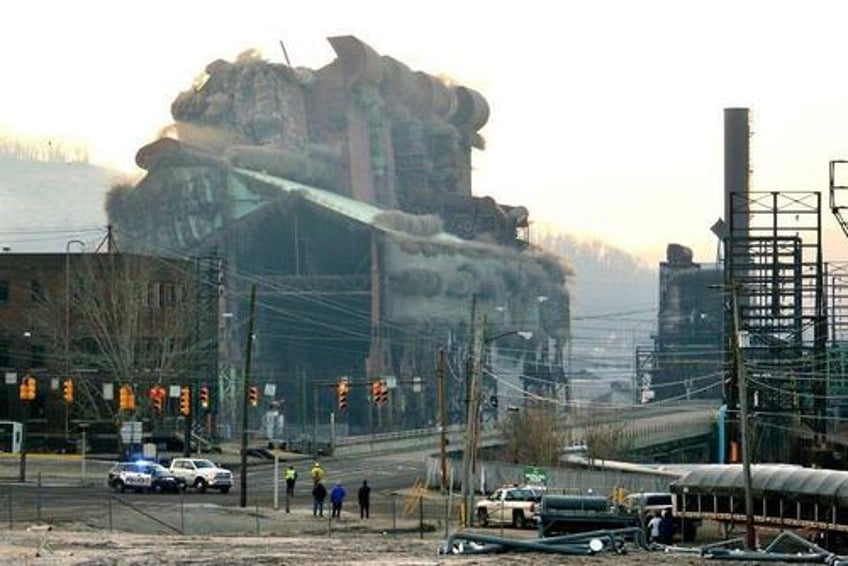

Thirty years ago, more than 10,000 people worked here at Weirton Steel. Now, the last 900 workers left have just lost their jobs.

“It’s just another scar to add on what people in power have done to our lives and our community over the past 40 years,” said one employee who declined to give his name, adding, “Honestly, how many times does this story have to be told before someone in power cares about our lives.”

He points to different buildings downtown, and all of them for him were “used to be this” and “used to be that.”

Ryan Weld of Wellsburg, 43, grew up in downtown Weirton right behind the local funeral home.

“When I was growing up in the ’80s, the mill was still going at full tilt with Weirton Steel employing 10,000 people, including my grandfathers,” he said.

The Republican state senator said things started to slow down here in the mid to late ’90s after the North American Free Trade Agreement was enacted:

“That dramatically changed the landscape of downtown, went from a bustling the last age group that remembers the shops and stores and restaurants of downtown.”

He believes NAFTA, signed by President Bill Clinton in 1993, essentially made it hard for companies like Weirton Steel, which had to follow strict and expensive Environmental Protection Agency guidelines compete with places like Mexico.

The towns all up and down the Steel Valley died hard.

“The legacy of the federal government and its refusal to properly enforce trade laws is nothing but empty mills and unemployed workers,” Weld said.

“That was true in the ’80s and ’90s, and that is true today.”

Forty years ago, the Democratic Party started to slowly shed its working-class base, but not quickly: Democratic officials would still show up for decades at union rallies, putting their arms around workers’ shoulders and telling them they have their back while at the same time enacting regulations and trade agreements that stripped them of their livelihoods and dignity and made ghettos of their once beloved communities.

By the 2012 Obama reelection, they traded their New Deal Democrat legacy voters for ascendant groups: minorities, young people, college-educated elites, and single women, all done without so much as a Dear John letter.

The Republicans inherited them, but most of their strategists running messaging and campaigns had no idea what to do with them, at least on the national level.

And then there is the press covering the voter who will decide the next president: Few if any of them come from places like Weirton or Youngstown, Ohio, so they have little understanding of their worldview. Things that give people from here purpose, such as living close to extended family, are not as valuable to someone who has been transient for most of a career.

In short, we are heading once again into an election where very few people in Washington truly understand how remarkably devastating this mill closure is.

Instead, it is a wire story at best, soon forgotten if measured at all. They truly do not understand how much the loss of the dignity of work has changed American politics.

That this tone-deafness is still happening 14 years after Barack Obama was given notice in the 2010 midterm elections and eight years after Donald Trump won the presidency is pretty staggering.

The Democrats once attracted these voters, but they’ve moved on to the social justice crowd and don’t appear to want to anymore. I’m not sure if Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) does, the press does not, and the new “very online right” is certainly not the reflection of a center-right voter in middle America. The online right just seems hell-bent on making them seem like Taylor Swift conspiracy theorists. (P.S. They’re not.)

Jeff Brauer, a political science professor at Keystone College, said Washington elites on both sides of the aisle, media elites, and now online conspiracy elites just don’t get Middle America even after this recent economically and politically difficult decade.

“Few things bond people/citizens together like trying to make a living in the real world, the dignity of work, and raising a family,” he explained, adding these bonds that cut across all divides — geographic, racial/ethnic, religious, gender, ideological/party, and even at times socioeconomic.

“If there is one thing we have learned over the past decade, it is that this bond over the difficulties of making an honest living can and does create unlikely coalitions of voters,” he said. “Even disparate voters from the likes of Bernie Sanders supporters to Trump supporters can agree on this.”

Indeed, economic dignity and survival make strange bedfellows.

Brad Todd, founding partner of OnMessage and co-author with me of The Great Revolt: Inside the Populist Coalition Reshaping American Politics, said one thing is for certain about 2024: “We are about to read a million new stories that quote zero people who are actually going to decide the election.”

Brauer said the dignity of work is at the very core of the American experience, “Yet the elites of this country still just don’t understand, while average Americans just keep getting financially squeezed more and more.”

Weld said it is incumbent on local elected officials such as himself to be the advocates of Middle America.

“I do what I do because of that. The empty buildings were already there when I was in college and high school, and it pisses me off,” he said. “I don’t think anyone fought hard enough for that from happening. We shouldn’t keep having to read again, again, another story about a town dying hard and a vacancy of no one caring.”