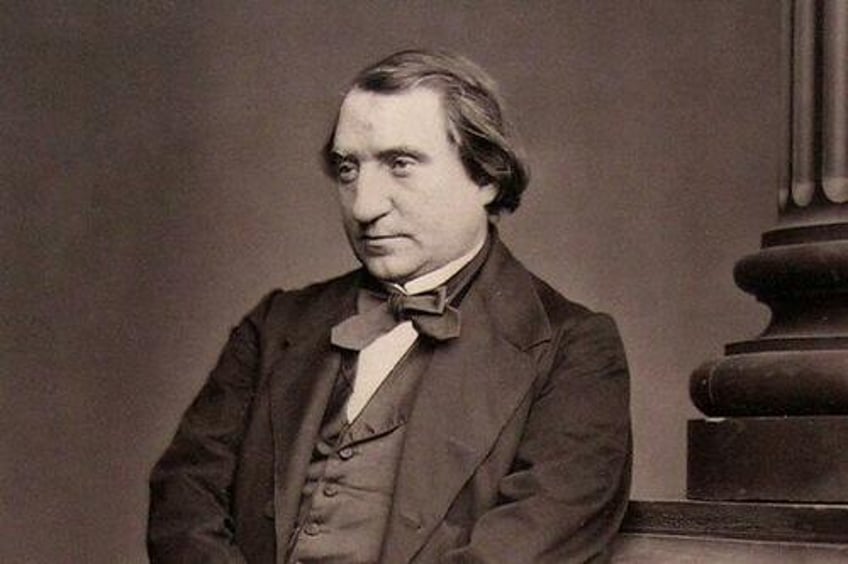

The year was 1882 and the speaker at the University of Paris, Sorbonne, was the essayist and historian Ernest Renan. His topic: “What Is a Nation?” The thesis rocked the continent and the world. What he called for, in essence, was nations by choice not by force.

I know that it is hard for us today to imagine that the words of any academic intellectual could or would have that impact but times were different. People in those days took intellectuals seriously, probably because they existed and earned their reputations.

Renan listed five markers of what could be considered a nation: heredity, geography, language, race, and religion/culture. All are potentially coercive, and tempted states with the power to grab people out of their lives and cultures and draft them into some grand project. This, he said, was inconsistent with liberalism as understood in the 19th century, which revolved around the freedom of choice.

The only kind of nationalism that is conscionable is that which calls for a regular plebiscite, the consent of the people. Nations are self-organizing, not created from without but from within. They can only be assembled by the consent of the governed.

Why should this even matter so much at the time? The 1880s were a time of dramatic change for the world in politics. The old multinational monarchies were dying out. The Papal states were slipping away under the pressure of the demand for political independence. The Spanish Empire was long gone and the Holy Roman Empire was a fading memory except to populate fashionable cocktail parties with personages of past prestige. The British Empire was already receding. The ethos of democracy was winning the day the world over.

There was an urgent need to decide some standard by which political independence was recognized as legitimate, without hurling the world into chaos and war. Renan’s goal was to provide such a standard.

A few decades later, this became supremely important following the catastrophe of the Great War. The multinational monarchies met their final doom and it fell to the world community to decide what nations are and could be.

In the end, and tragically, it was left to the victors in the war to decide. That meant leaving it to a deeply unpopular U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, who only held office due to a split in the Republican Party that swept him into office in 1912. He barely won reelection in 1916 but following the Great War, it fell to his office to determine which European nations would be granted legitimacy. He knew almost nothing about the topic, which left it to the lobbying of European leaders to explain the lay of the land to him.

The results were obviously imperfect. Together with the rough terms of peace with the Versailles Treaty, the defeated foes were left with huge debts and an incentive to inflate, and a seething political anger that intensified over the decades. The result was the most dreaded outcome of all: a second world war.

In any case, Renan’s template for the good kind of nationalism dominated after the Great War. All responsible intellectuals saw nationalism as a path to peace and freedom in a war-torn continent. To form one’s nation by consent was seen as an extension of freedom. Wilson called this “self-determination” and mostly people agreed that this was the ideal. This kind of nationalism was regarded as the best post-monarchical model for liberal international relations.

My own top intellectual influence is the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises. His 1919 book was “Nation, State, and Economy.” In his view, language (speech) was the best basis to define nationhood. It’s hard for Americans to understand this since it would seem to put us in one nation with England and Australia. At the time, however, this theory made sense in a European context. Think of the strange and unsustainable amalgams of Yugoslavia or Czechoslovakia; a language-centered nationalism could have predicted their demise.

Mises himself was Austrian, of Jewish heritage, and was thinking in those terms.

If a group was united in language, he argued, it was a viable nation. And this is a good path to peace.

“The nationality principle above all bears no sword against members of other nations,” he wrote. “It is directed in tyrannos. Therefore, above all, there is also no opposition between national and citizen-of-the-world attitudes. The idea of freedom is both national and cosmopolitan. It is revolutionary, for it wants to abolish all rule incompatible with its principles, but it is also pacifistic. What basis for war could there still be, once all peoples had been set free? Political liberalism concurs on that point with economic liberalism, which proclaims the solidarity of interests among peoples.”

It’s fascinating to read that passage in light of what came after. As it turns out, a different form of nationalism was rising in Germany from 1923 and onwards. It absolutely bore a sword. It took the idea of race and ran with it, postulating that the German nation should extend to everyone of “Aryan” race, purging territories of groups that fall outside that designation. In this, the rise of German nationalism drew on race studies of the late 19th century, and trampled all over both Renan’s postulates and Mises’s hopes for the future of nationalism.

What makes for fascinating reading is Mises’s own 1944 wartime history of the rise of the Nazis. His book “Omnipotent Government” offered a diametrically opposed view of nationalism. In chapter after chapter, he shredded the racial view of political community, condemned all forms of imperialism, and blasted militarism based on nationalistic ambitions. Clearly, his attitudes had changed in light of events. The Second World War caused him to turn against the ideology of nationalism, treating it as potentially aggressive and the enemy rather than the friend of freedom.

The purpose in recounting this history is simply to say that there is not one correct view of nationalism. It depends on the historical and political context and the cultural and political assumptions behind nationalist feelings.

After the end of the Cold War, many had hoped that the United States would return to its roots as a peaceful commercial Republic, doing as George Washington said: trading with all and making political alliances with no one, being a light unto all nations while staying out of the internal affairs of foreign nations. This view was widely held on the left and right. However, many in power had different views. They wanted to deploy the newly earned status as the world’s only superpower to become the globe’s policeman, with war after war, intervening in every border dispute or otherwise.

It was in those days that my own attitudes on nationalism shifted. On matters of political organization, nationalism struck me as mostly benign. But on matters of race and migration, globalism seemed to me to be the right answer. Yes, I was a product of my times and did not know it.

What I and others had not seen coming was something different, the rise of globalist institutions—built from both public and private monies—that had every intention of trampling on sovereign rights, not only of the domestic political community but also on foreign peoples.

This new globalism was never more on display than in the pandemic policy response, which the World Health Organization urged every nation to adopt the strategies and tactics of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in China, locking citizens in their homes and attempting to protect health through use of extreme force. All nations in the world adopted this tactic, save only a few, and this approach wrecked economies, destabilized political systems, and demoralized people of the world. If nothing else, this experience highlighted the dangers of globalist ideology.

Here we are nearly a century and a half after Renan’s Sorbonne lecture and still grappling with the great question of nationalism. We do have experience to draw on. We know now that nationalism can be a check on globalist power, exactly as Mises imagined it after the Great War, but we are also aware of the dangers associated with chauvinism and imperialism in the name of nation building too, as Mises also mapped out.

For now, I’m inclined to have a warmer view toward the nationalist temperament if only to guard against the real and present threat of a globalist ruling class imposing rules on the entire planet, creating a regime for the world over which national political systems have no influence. This danger is real and all around us.

For now, the urge to reassert national sovereignty—whether in the form of American patriotism or European skepticism toward the European Union—strikes me as a necessary frame of mind to get us back to the fundamental principle of freedom itself.

In theory, the path toward freedom seems easy: human rights, governments that are limited to strict functions only, and diplomacy over war. In practice, this ambition ends up taking a circuitous route. It was true in the last century and it is true in ours as well.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.