The Founding Fathers understood from the beginning that the American Revolution was a matter of conscience and courage. The Patriots, having signed on to the Declaration of Independence, committed their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to the cause of liberty.

Indeed, the American Revolution was an international stirring of conscience as others, overseas, made the same commitment. The prayerful hope was for a new republican order for the ages, spreading worldwide, replacing the tyranny of kings and queens with the sovereignty of free men and women.

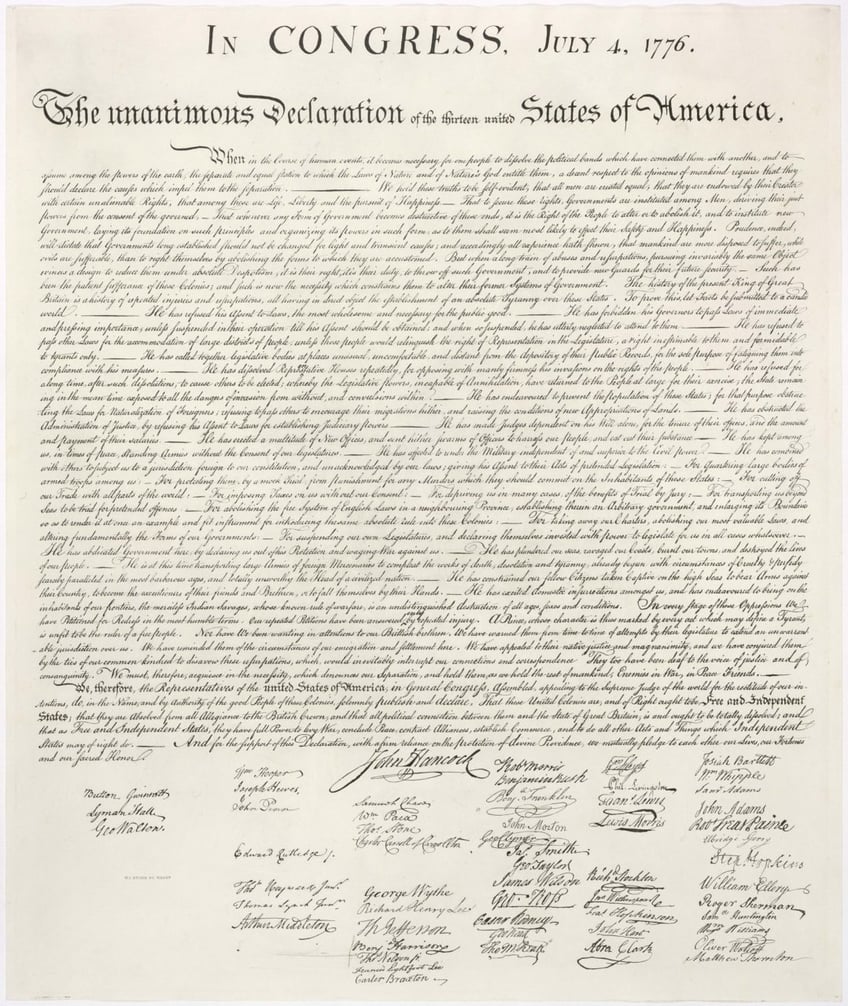

Mindful of this opportunity, the authors of the Declaration, released on this day, 248 years ago, made their pitch to world opinion. Having started the rebellion in America, they wrote, “[A] decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.” They then described “a long train of abuses and usurpations” to justify the revolt.

Better known in the Declaration, of course, are the ringing words that continue to inspire: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

The effect was electric. All over the planet, lovers of liberty saw the American Patriots’ fight as their fight, too.

In fact, some were so inspired that they traveled from Europe across the Atlantic Ocean at their own expense — at a time when the westward voyage took at least six weeks — to aid the revolution. Not surprisingly, they were almost all wealthy aristocrats, high-born in their home countries, nonetheless idealistically eager to aid this new experiment in freedom and civic equality.

From France came de Rochambeau and de Chastellux. From Germany came de Kalb and von Steuben. From Poland came Kościuszko and Pulaski — and the latter died in the fighting. He is buried in Savannah.

In fact, even before the Declaration came the shot heard ‘round the world. That was on April 19, 1775, when the Patriots of Lexington and Concord squared off against the British redcoats.

The Battles of Lexington and Concord, a digitally restored reproduction from an original of the period. (Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

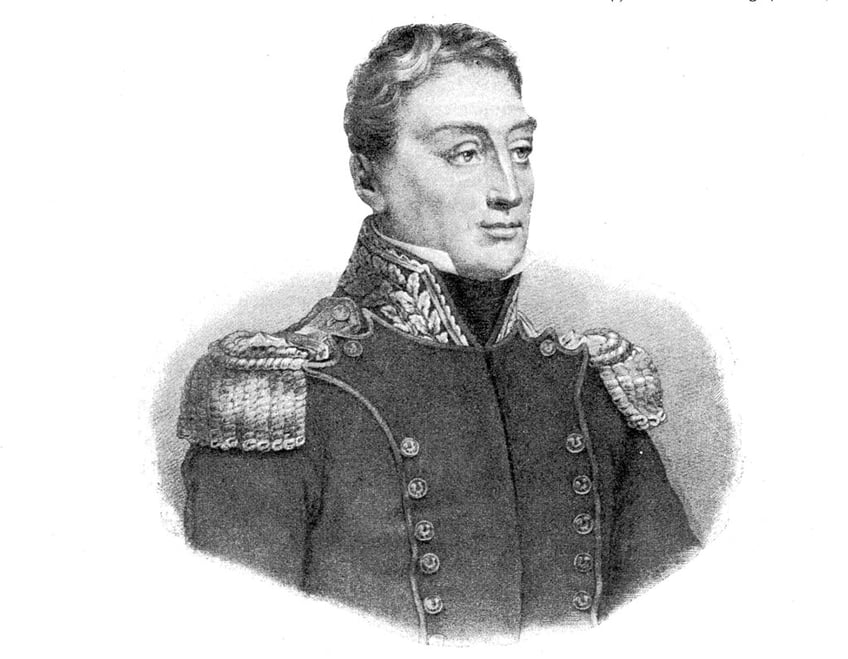

Perhaps the greatest figure who heard and hearkened to that loud sound was Frenchman Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette. As the name suggests, he, too, was a nobleman, and yet his soul was republican.

As a young military officer stationed in Metz, 200 miles west of Paris, La Fayette first learned of the gathering revolution at a dinner on August 8, 1775. The guest of honor that night was a Briton, the Duke of Gloucester, younger brother of King George III — George being the arch-enemy of American independence.

His royal blue blood notwithstanding, Gloucester sympathized with the Americans. The 18th century was, after all, the Age of Enlightenment, when people of all ranks were thinking new thoughts about modernity and progress.

The Duke recounted news about the “peasants,” as he called them, in the Massachusetts Colony fighting back against the British — and also about them tossing tea into Boston Harbor (that had actually been two years before).

As recounted by historian Rupert S. Holland, the Duke admired the courage of the American farmers but added with a sigh that it would be impossible for them to win against regular troops unless experienced officers could lead them.

Whereupon, La Fayette exclaimed, “Then tell me, I pray you, how one may do it, monseigneur. Tell me how to set about it.” Gloucester answered that perhaps La Fayette himself could help, to which the young man replied, “For see, I will join these Americans; I will help them fight for freedom!”

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (September 6, 1757 – May 20, 1834) (Bildagentur-online/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

It took him two years, but on June 13, 1777, La Fayette was here, making landfall in George Town, South Carolina. Thereupon, he joined the Continental Army, volunteering to serve without pay. He soon found himself on George Washington’s staff, saying humbly, “I am here to learn, not to teach.”

In 1779, he sailed back to France as part of a successful mission to enlist that country’s aid in the war against Britain. In 1780, he returned to America and, the following year, was with General Washington at Yorktown when the British surrendered.

Today, a grateful nation remembers La Fayette’s service; some 150 places here are named after him. The other foreign helpers, too, are immortalized on our soil. There’s a Steubenville, Ohio; a DeKalb County, Georgia; and a Pulaski County, Arkansas — to name just a few of the many geographical tributes.

Yet if most seek to remember our glorious history, others seek to misremember it. Case in point: The “Appeal to Heaven” (ATH) flag. Its name a reference to John Locke’s pro-liberty treatise from the 17th century, ATH might have been flown as early as 1775 at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Hard to think of a grander pedigree than that.

“Appeal to Heaven” flag (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

But in May 2024, the New York Times reported (if that’s the right word) that the Appeal to Heaven flag was flown by the family of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito. The Times described flag, glaringly incorrectly, as “provocative” and “troubling.” One liberal “scholar” was trotted out to say that ATH represented “a theological vision of what the United States should be and how it should be governed.”

Fortunately, today’s patriots took it upon themselves to set the record straight. They pointed out, for example, that the flag has long been flying all over the country, even in liberal enclaves — although, when this fake-news controversy erupted, the City of San Francisco pulled it down to show solidarity with Alito-haters and the Times.

We can see: Two-and-a-half centuries after the Patriots won our freedom, today’s patriots must still contend with historical falsehood, maybe even malice.

To be sure, our American Experiment has never been easy. Yet with God’s grace — in the Declaration, the Founders also appealed to “the Supreme Judge of the world” — we can push past the nattering nabobs of negativism.

In 1787, the Revolution having been won, George Washington opened the Philadelphia convention with the solemn ordainment, “Let us raise a standard to which the wise and the honest can repair.” That would be the American flag, representing the soon-to-be crafted Constitution.

The signing of the Constitution of the United States with George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Oil painting on canvas by Howard Chandler Christy, 1940. (GraphicaArtis/Getty Images)

Today in America, a new kind of revolution is brewing: against the administrative state, against progressive bureaucrats pushing diversity, equity, and inclusion policies and transgenderism, against open-borders and gun grabbers, against woke capital, against green de-growthers who wish to ban everything from gas stoves to cow emissions, against the Great Resetters of the Davos World Economic Forum.

It is, indeed, a long train of abuse. So a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires today’s patriots to declare themselves, explaining their new campaign for liberty. And if we do, we’ll find, as we did a quarter-millennium ago, that we have plenty of allies around the world.