Shell, Europe's largest oil company, has quietly shelved the world's largest corporate plan to develop carbon offsets, after CEO Wael Sawan laid out an updated strategy for the company that included cutting costs and doubling down on profit centers (oil and gas) - which notably omitted any mention of the company's prior commitment to spend up to $100 million per year to build a 'pipeline' of carbon credits as part of the firm's promise to achieve 'net zero' emissions by 2050, Bloomberg reports.

The pullback reflects both Sawan’s renewed commitment to the oil-and-gas business that generates most of Shell’s profits, and an admission that the prior goals were simply unattainable. Over the past two years, Shell barely made a dent. It spent $95 million, less than half of its initial budget, to build or invest in a portfolio of carbon projects from Western Africa to the Brazilian Amazon to Australian farmlands. They’ve generated few if any offsets, and Shell has struggled to find projects that meet its standards for quality.

According to investigations by Bloomberg Green (how cute), many offset programs don't deliver the environmental benefits they promise. In announcing their now-shelved programs, Shell sought to solve that problem with stringent requirements, deep pockets, and engineering expertise. What they learned was something any idiot could have told you: there's no effective way to maintain a large enough offset program to make a difference.

"It’s really hard to get scale from high-quality credits," said Carbon Market Watch's Gilles Dufrasne. "The two forces," being volume and quality, "work against each other."

Shell's carbon debacle was inspired by a 2017 Nature Conservancy paper which suggested that nature-based solutions would be a cost-effective means to offset carbon.

And - surprise, the academics were wrong again...

For example, four years into a plan to partner with Forestry and Land Scotland to plant over a million trees to generate "pending issuance units" (unborn carbon credits), they've accrued less than 0.02% of their initial goal in terms of carbon sequestration.

And in Canada, Shell's efforts to secure land for credits has turned into a total disaster despite the company bragging about the endeavor on its website. The company has also failed to hit its $100 million investment target, spending only about $69 million last year, which accounts for less than 1% of its total capital expenditure.

Georgeclerk | Getty Images

Another project to restore mangrove trees in Senegal, which began in 2019 and has been operated by Belgian nonprofit WeForest, won't even start producing carbon credits until 2025. Shell has also walked away from potential goldmines like the Delta Blue Carbon Project in Pakistan which would cover an area roughly twice the size of London. While the 'fundamentals were sound,' per Bloomberg, the company had concerns over the integrity of the project's local partners, as well as the origins to the land rights.

A spokesperson for Indus Delta Capital, which runs the project, said shareholders and directors in the project have been subjected to rigorous due diligence and the process by which licenses and permissions were granted is “in line with the rules of business” prescribed by both the national and regional governments. -Bloomberg

Shell has also broken ties with a Montana grasslands project run by Vermont-based Native Energy due to disagreements over deal structures and the potential use of credits to label fossil fuels as carbon neutral.

For Native’s part, chief executive officer Jeff Bernicke said it terminated discussions with Shell because “there was not a fit between their plan and Native's goals and values.” There was also a concern that the credits would be used to label fossil-fuels as carbon-neutral. A spokesman for Shell said the company has a robust due diligence process and it does not comment on specific projects or the contractual agreements.

Shell's strategy now seems more attuned to secrecy and selective partnership. The company keeps some ventures under wraps, like its involvement in the Peruvian Amazon and an Indonesian forestry venture dubbed "Sun Bird," perhaps to ward off competition from oil industry peers who are also elbowing their way into the carbon-credit market.

Backup plan?

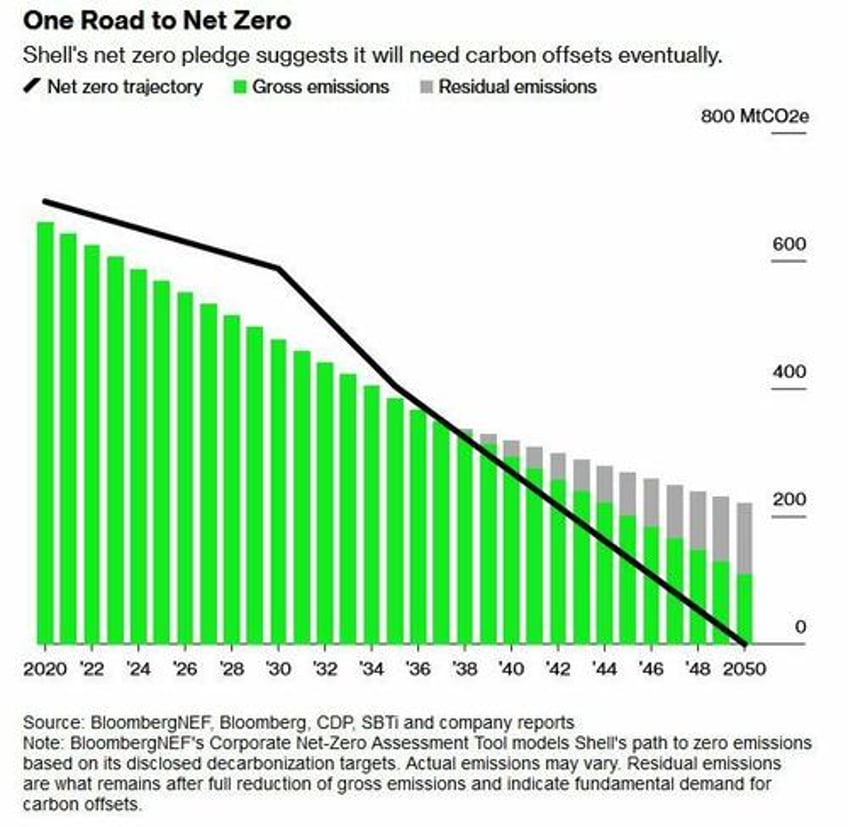

While Shell's expensive quagmire into carbon credits may have crashed and burned, the company has a backup plan - appease climate alarmists by simply buying 'low-quality' carbon credits to achieve its lofty goals of becoming 'carbon neutral' by 2050.

In the words of Adam Matthews, chief responsible investment officer at the Church of England Pensions Board, "They're no longer aligned with trying to navigate the transition in the same way that we had previously perceived."