States that have permissive policies on squatting—a growing phenomenon in the United States—need to make the practice a criminal offense, the writers of a new report from Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF) say.

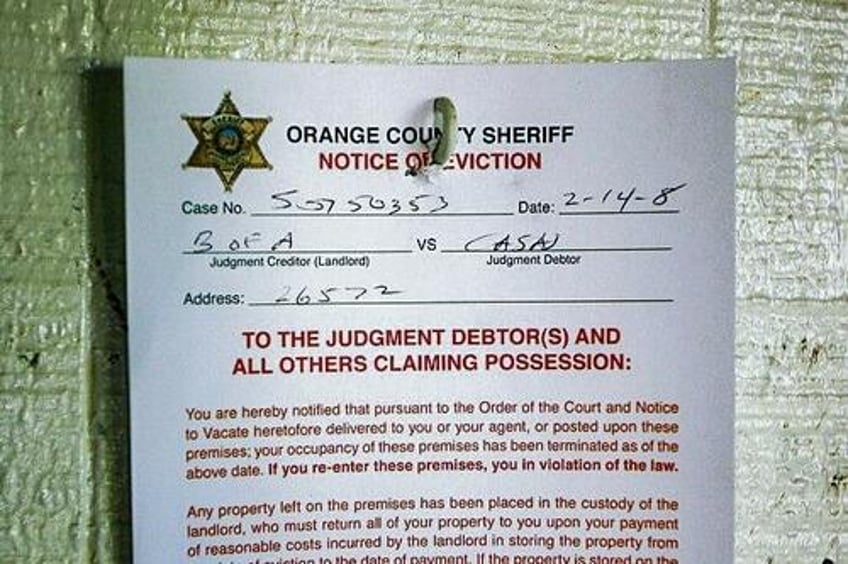

Squatting is occupying an unoccupied or abandoned area of land or a building without having legal permission to use it. Although squatters don’t pay rent and sometimes damage the properties they take over, evicting them can be difficult and costly.

Most states are reluctant to allow criminal prosecution of squatters as trespassers and prefer treating incidents as landlord and tenant disputes. Police who wish to avoid potentially violent confrontations often don’t want to take direct action and instead advise property owners to seek eviction orders from judges.

Kyle Sweetland, strategic research manager at PLF, is a co-author of the report, “Locking Squatters Out: How States Can Protect Property Owners.”

Sweetland acknowledged that there are some thinkers who say squatting is a legitimate means of redistributing wealth.

On the other hand, “legal scholars argue that states’ treatment of squatting as a civil rather than criminal offense amounts to a government-approved taking of private property without just compensation, a violation of property owners’ Fifth Amendment rights,” he said in an Aug. 13 interview.

States are “letting somebody live rent-free at your home while you have to wait for this much longer process” to unfold to regain possession of it, he said.

Model Legislation

PLF, a national, nonprofit public interest law firm, has developed model legislation called the Stop Squatters Act that state legislatures can use to level the legal playing field, he said.

The legislation declares that “the right to exclude others from entering, and the right to direct others to immediately vacate, residential and commercial real property are fundamental property rights.” It also provides civil and criminal penalties for squatters.

PLF senior attorney Mark Miller said, “It is long overdue that we start treating squatters like what they actually are—trespassers.”

“Squatters illegally take property that doesn’t belong to them, and some sell the owner’s belongings, trash the property, or use it for illicit activities,” Miller said in a statement.

“They shouldn’t be given special legal protections.”

The White House has acknowledged that squatting is a problem but has been wary of promoting federal policies to deal with it amid calls for national anti-squatting legislation.

On April 8, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said “This is a local issue” and that it was “critical that communities take action to address this issue in a way that works best for them.”

“It is important that we protect the rights of both property owners and also renters. But I also want to be clear here: Anyone found guilty of a crime should be held accountable,” she said.

Statistics Show Squatting on the Rise

Quantifying the problem is difficult because the FBI’s national crime database doesn’t track squatting.

The PLF report says national statistics on squatting incidents are unavailable, but in 2023, the National Rental Home Council surveyed its members and reported that Atlanta (1,200), Dallas (475), and Orlando (125) experienced the greatest numbers of homes subjected to squatting at some point, although the figures weren’t broken down by year.

But case counts for litigation against squatters that were obtained from civil court records in Georgia and New York showed an upward trend that began in 2019.

The case count in Georgia rose from three in 2017 to 50 in 2021 and 198 in 2023. In New York, there were nine cases each in 2020 and 2021, and 62 in 2022. The figure for 2023 fell to 37.

But these figures likely understate the true number of cases filed because the records examined for Georgia covered courts in only 25 of the state’s 159 counties, and the records for New York exclude local civil courts in towns and villages, the report says.

Meanwhile, public concern over squatting has caused eight state legislatures to pass new laws to criminalize the practice and make it easier for property owners to remove squatters, according to the report.

Although most states treat squatting as a civil matter to be resolved in court, as of May 2024, Alabama, California, Florida, Georgia, Nevada, Tennessee, Washington, and West Virginia have laws on the books that make squatting a crime.

Legislation has been introduced in North Carolina, South Carolina, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Pennsylvania that would bolster property owners’ rights against squatters.

Some states, such as Colorado, have created an expedited legal process for removing squatters. Since April, Georgia has had a law in place that cuts the time for repossession of a property to 10 days from eight months, the report says.

Since July, Florida law has allowed property owners to ask law enforcement to immediately remove squatters. The local sheriff can remove an unauthorized person if ownership of the property can be verified. To guard against abuse, a person wrongfully removed can sue for damages equal to triple the fair market rent.

Sweetland said that the attention now being paid to squatting has helped some legal reforms happen and that this is giving homeowners “a much better process of getting repossession of their homes.”