According to Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, “The Federal Reserve's monetary policy independence is an important and broadly supported institutional arrangement that has served the American public well.”

According to Professor Thomas J. Weber at Pace University Lubin School of Business, this is nothing but a myth.

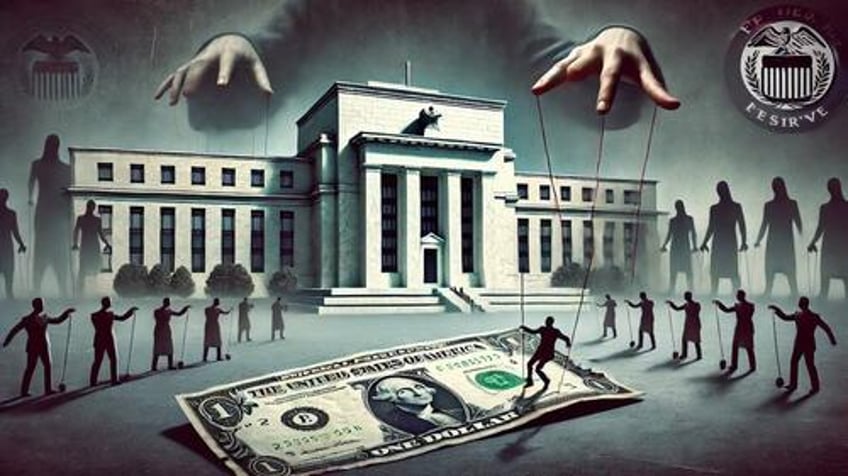

In a recently published paper, Webster argues that the relationship between the Fed and the U.S. government is more like a captive’s relationship with his captor.

“Something like the Stockholm syndrome seems to describe the institutional relationship that exists between the U.S. Congress and the White House (the captors), and the Federal Reserve (the captives).”

He goes on to insist, “The Fed is just another branch of the U.S. government with a political agenda.”

Webster argues that “a more economic description of the Fed’s relationship with the executive and legislative branches is regulatory capture (also called agency capture).”

“This occurs when a government agency is politically co-opted into serving the special interests of the institution it is meant to be regulated.”

While the Federal Reserve isn’t supposed to regulate Congress, it is tasked with independently maintaining “price stability.” Webster asserts that the central bank abandons this mandate and instead prioritizes enabling government borrowing and spending. In effect, the central bank is the engine that drives the massive U.S. welfare-warfare state.

“To soften the increased debt service burden, the Fed purchases newly issued U.S. Treasury securities not sold to the public with 'printing press' money charging below-market interest rates. By inflating the money supply, a part of the increased financial burden is passed along to the household sector in the form of higher prices. The underwriting of congressional spending is at the heart of the symbiotic relationship that exists between the Fed, the president who nominates monetary policymakers, and the Senate that ratifies their appointment.”

Webster described a policy known as quantitative easing (QE). Without the Fed’s intervention by keeping its thumb on the bond market, the federal government wouldn’t be able to borrow and spend to the extent that it does.

Ben Bernanke ran the first QE operation in the U.S. in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. When the Fed began buying U.S. Treasuries, Bernanke insisted the Fed was not monetizing debt. He said the difference between debt monetization and the Fed’s policy was that the central bank was not providing a permanent source of financing. He said the Treasurys would only remain on the Fed’s balance sheet temporarily. He assured Congress that once the crisis was over, the Federal Reserve would sell the bonds it bought during the emergency.

Of course, that never happened.

The Fed doubled down on quantitative easing during the pandemic. During the government shutdowns, the Fed immediately pushed interest rates to zero and pumped nearly $5 trillion into the U.S. economy through quantitative easing. In so doing, the central bank monetized a big chunk of the debt accumulated during the pandemic era. The Fed didn’t end QE until the end of 2021.

According to Webster, “The Fed was less concerned with the effect that expanding budget deficits were having on the general price level and more concerned with abetting the budget agenda of the White House and Congress.” He cites a FOMC insider who said it was politically difficult for the Fed to end QE “because the Congress and private-sector business interests had become addicted to cheap money.”

Webster isn’t just making wild assertions. The paper summarizes the results of an empirical investigation “into the relationship between fiscal and monetary policy” during the pandemic era in particular.

While he concedes that the results are “subject to interpretation," Webster concludes, “These results, however, are consistent with the supposition that the Federal Reserve was complicit in funding federal government deficits with printing press money.”

“The Fed is not the bastion of sound monetary policy. Rather, it is just another politically coopted agency of the federal government. From the onset of the GFC until the first quarter of 2022, the Fed unapologetically pursued a low-interest rate policy with little regard to the threat that it posed to price stability.”

Webster notes that the Fed essentially serves three clients: government, businesses, and households.

“Regrettably, the best interests of the government and business sectors take precedence over the concerns of the household sector.”