By dropping rates dramatically only a month and a half before an election, the Fed is playing with fire. The election, by all visuals, would seem to pit the establishment against an insurgent populist movement. Regardless of the countercyclical motives, it’s a move that has been widely seen as deeply political. And that invites resentment and retribution.

Let’s examine the case for the rate cut. Rates are not tremendously high in real terms. The inflation fight of the last two years seems to have drawn down the rate of price increases, though the battle is far from over. But now the Fed believes it has another problem with which to deal, namely weakness in the labor market.

To get ahead of a possible impending recession compels the Fed to engage in another round of easing. That’s the thinking in any case. But there is the problem of facts. The recessionary conditions are everywhere except on official paper. Bankruptcies are quite high already. Inflation is underestimated and growth overestimated. At this point, everyone in the know is aware.

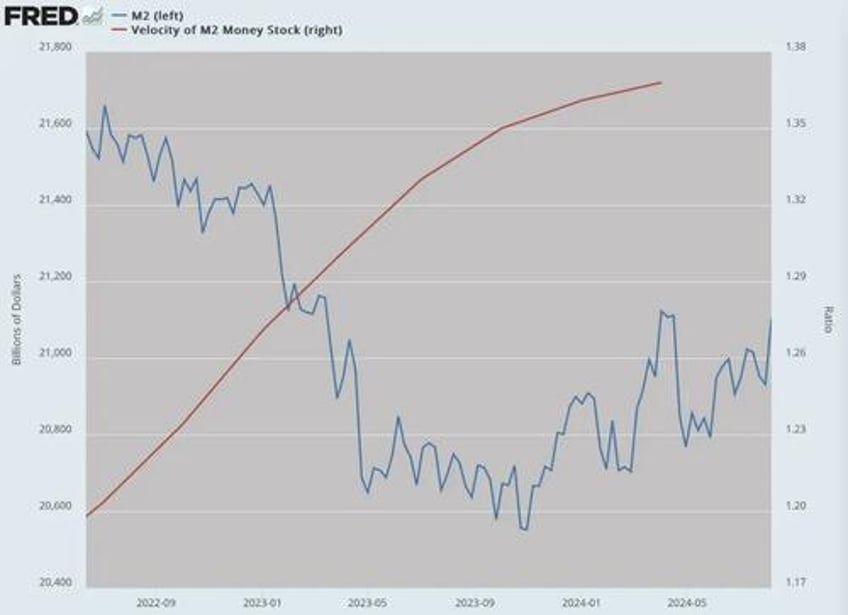

There is another factor of which many people are unaware. The money stock is already on the increase, either due to relaxed lending standards, more debt purchases by the Fed, or both. This has combined with an inevitable increase in money velocity have followed the risk aversion of the lockdown years, which further fuels prices pressure. That could show up in the retail sector or it could show up in financials. In either case, this is not economic growth but rather its illusion in the form of monetary depreciation.

(Data: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), St. Louis Fed; Chart: Jeffrey A. Tucker)

The uptrend in money stock is nearly a year ongoing following the previous year of decline.

We need to reacquaint ourselves with the concept of a lag. What the Fed does today does not show up in its real effects until 12 to 18 months after the fact, depending on a range of other factors. We know this from the best-quality research of 100 years of monetary policy and its impact.

Very likely, the reduced price pressure we are experiencing right now is due to declining money stock from two years ago. That also means that the shift to greater easing now and in the future will hit us sometime next year.

If the Republicans are ruling the Congress, the presidency, or both, there will be hot fury alive in the land. To the extent that people today are unwilling to blame the Fed for the 25 percent decline in purchasing power over four years will likely change. At that point, the Republicans will be screaming: this is enough. The Fed created the last range of problems and it has created this one as well.

Scour the U.S. Constitution and you will find nothing about this beast called the Fed that was created in 1913. Its purpose was to deploy science in defense of economic stability and low inflation. Almost immediately, the result was the opposite: more business cycles, more inflation, and more government profligacy. This is all because the central bank works as a kind of blank check for government.

Moreover, the Fed created a cartel-like arrangement among banks, which were once products of free enterprise but immediately became a privileged monopoly serving its member banks and the government. The most immediate result of the Fed’s creation was the first World War, which otherwise could not have been funded.

The problem grew worse over the decades but consider the following. No state government has a central bank. They have to pay for what they buy with tax dollars or float debt that is subject to a default premium. That doesn’t prevent financial profligacy but at least it introduces a check. The federal government has no such limit. Its bonds are considered as good as cash for only one reason: the Fed’s ability to print our way out of crisis.

There is nothing necessary about such an institution. To be sure, eliminating it would amount to a shock to the system of the most severe sort. Wall Street would scream. Central banks around the world would panic. Big media would denounce the move, and all establishment economists would be in freak-out mode. All that aside, there is no getting around two crucial facts: such an institution is enormously powerful but nowhere in the Constitution, and none of its grand promises have worked out.

The possibility of abolition aside, there are many ways in which Congress could assert more control over the Fed. It has no control now. As Rand Paul has long urged, Congress could demand an independent audit to discover the fullness of where the money is coming and going without trusting the Fed’s reports alone. Every major corporation and even medium-sized company does this. Why is the Fed exempt?

It could make other changes to the Fed’s discretion over the discount window and bank monitoring. It could even take back a portion of monetary control itself, perhaps tasking the Treasury with new monetary functions. To the Fed, this would compromise its much-celebrated independence. But many have started to doubt how many compromises the Fed has to make in order to preserve it. For all the world, it seems these days like a highly political institution as every central bank necessarily must be.

In the ideal world, the dollar would restore its gold-backed status and the Fed would be deleted entirely, thus restoring the pre-1913 days of high growth, rising purchasing power, and decentralized banking. The goal would be to normalize the industry so that it worked like every other, as in free enterprise with the possibility of bank failure and normal competitive pressure.

This would have the advantage of unplugging the printing press and thereby getting the debt under control.

Getting from here to there would be technically difficult, but that is not the real problem. The real problem for the gold standard has been the lack of political will. That could be changing now, as more lawmakers than ever are livid at what is taking place right under our noses.

In other words, the Fed this time could be preparing the way for its own demise. Some might say: it’s about time. This time next year, as inflation is resurgent and as the dollar resumes its purchasing decline in a way that could be even worse than the most recent wave, more people will be recruited among the ranks of the critics, doubters, and even abolitionists.

We do seem to have crossed some invisible line. The Fed is now considered both culpable and responsible in which that was not in the past. The next round of inflationary pressure should and will be directly blamed on the Fed.