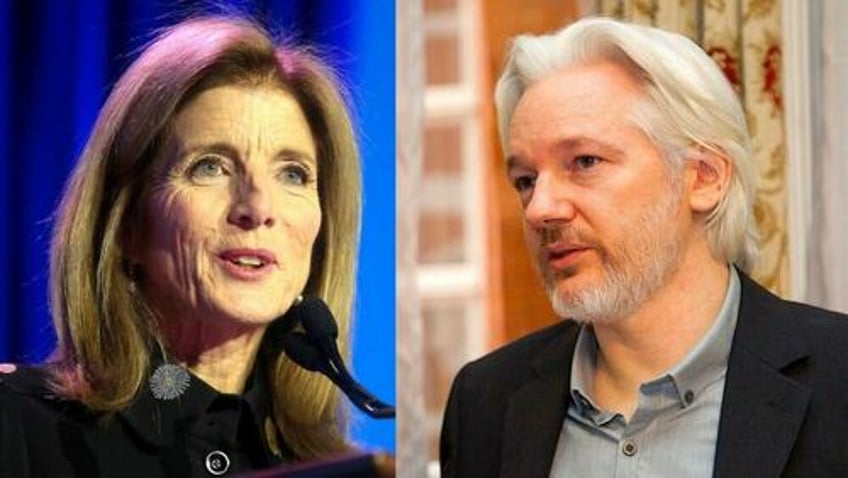

The U.S. ambassador to Australia believes a plea bargain could free imprisoned WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange, allowing him to serve a shortened sentence for a lesser crime in his home country.

Caroline Kennedy told The Sydney Morning Herald in a front-page interview published Monday that the decision on a plea deal was up to the U.S. Justice Department. “So it’s not really a diplomatic issue, but I think that there absolutely could be a resolution,” she told the newspaper.

Kennedy noted the firm comments by U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken on July 31 in Brisbane that,

“Mr. Assange was charged with very serious criminal conduct in the United States in connection with his alleged role in one of the largest compromises of classified information in the history of our country. … So I say that only because just as we understand sensitivities here, it’s important that our friends understand sensitivities in the United States.”

Despite Blinken’s strong words, Kennedy said: “But there is a way to resolve it. You can read the [newspapers] just like I can.” Gabriel Shipton, Assange’s brother, told the Herald: “Caroline Kennedy wouldn’t be saying these things if they didn’t want a way out. The Americans want this off their plate.”

The newspaper said there could be a “David Hicks-style plea bargain,” a so-called Alford Plea, in which Assange would continue to state his innocence while accepting a lesser charge that would allow him to serve additional time in Australia. The four years Assange has already served on remand at London’s maximum security Belmarsh Prison could perhaps be taken into account.

Going to the US for the Plea

David Hicks was an Australian imprisoned by the United States in Guantanamo for five years. He was ultimately released by the U.S., after pressure from the Australian government, when he agreed to an Alford Plea, in which he pled guilty to a single charge, but was allowed to assert his innocence at the same time on the grounds that he understood he would not receive a fair trial.

Hicks was returned to Australia where he served an additional seven months in prison. His conviction was then overturned on appeal when it was established that the charge of giving “material assistance to terrorists” was not yet a crime on the books at the time of his arrest. The Herald quoted Don Rothwell, an international law expert at Australian National University in Canberra, as saying that Assange would have to travel to the U.S. in order to work out the plea deal.

“Everything we know about Julian Assange suggests this would be a significant sticking point for him,” Rothwell said. “It’s not possible to strike a plea deal outside the relevant jurisdiction except in the most exceptional circumstances.” However, Bruce Afran, a U.S. constitutional attorney, told Consortium News‘ CN Live! webcast in May that it would indeed be possible for Assange to remain in Britain to work out the deal.

“Usually American courts don’t act unless a defendant is inside that district and shows up to the court,” Afran said. “However, there’s nothing strictly prohibiting it either. And in a given instance, a plea could be taken internationally. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. It’s not barred by any laws. If all parties consent to it, then the court has jurisdiction.”

Afran said that after seven years in the Ecuadorian embassy in London and four years in Belmarsh, Assange “obviously would have a fear of coming to the U.S. And our prison system is often known for rough treatment in terms of management units and solitary confinement.”

Afran said it was understandable that Assange would not trust the U.S. to follow through on a deal if he went to America. “The U.S. sometimes finds ways to get around these agreements,” Afran said. “The better approach would be that he pleads while in the U.K., we resolve the sentence by either an additional sentence of seven months, such as David Hicks had or a year to be served in the U.K. or in Australia or time served.”

Shipton told the Herald that his brother going to the U.S. was a “non-starter.” He said: “Julian cannot go to the US under any circumstances.” Afran said Assange would not necessarily have to plead to an espionage or computer intrusion offense. “He could plead simply to mishandling official information or even, in the worst case scenario, conspiracy to mishandle official information, a far lesser charge,” he said.

“That would also resolve the case and probably give the U.S. its satisfaction and would allow Julian essentially to hold his head up high after all these years,” said Afran. A conspiracy to mishandle defense information would amount to criminalizing the reporter-source relationship.

Awaiting High Court Hearing

Afran also said that Assange’s side could initiate the plea offer. On May 22, two days before President Joe Biden was due to visit Australia on a trip he then canceled, Assange lawyer Jennifer Robinson said for the first time on behalf of Assange’s legal team that they would consider a plea deal.

Robinson told the National Press Club in Canberra:

“We are considering all options. The difficulty is our primary position is, of course that the case ought to be dropped. We say no crime has been committed and the facts of the case don’t disclose a crime. So what is it that Julian would be pleading to?”

Assange remains in Belmarsh awaiting a final, 30-minute hearing before the High Court of England Wales, which is on summer recess until Oct. 1. Assange’s lawyers will attempt to reverse a decision by the High Court not to hear his appeal against the home secretary’s extradition order and against most of the lower court’s ruling in his extradition case.

That court in January 2021 ordered Assange released on health grounds and the conditions of U.S. prisons but sided with the U.S. on every other point of law. The U.S. then won its appeal before the High Court, which overturned the order to release Assange.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese is due to visit President Joe Biden at the White House at the end of October at which time Assange supporters may hope that an arrangement to send Assange to Australia could be finalized.

But the High Court could convene before that. If it rejects Assange’s final appeal, he could be put on a plane to Alexandria, VA where he faces up to 175 years in a U.S. dungeon for publishing accurate information about U.S. war crimes and corruption.

Greg Barns, a human rights lawyer who advises the Assange campaign, told the Australian Associated Press that Assange had come between the U.S. and Australia as Washington gets Canberra’s cooperation to set up new U.S. military facilities in Australia as it ramps up pressure on China. “It’s clearly a diplomatic issue because it has engaged the prime minister and the foreign minister – it’s not an ordinary, run-of-the-mill extradition case,” Barns said. “This matter has become a sticking point in the alliance,” he said.