Internet watchdogs generally agreed that Internet freedom declined once again in 2024 – the fourteenth loss in a row, according to Freedom House.

The major drivers of declining Internet freedom over the past year were the rise of military juntas, the spread of Islamist speech codes, and the general tightening of authoritarian rule – including authoritarianism spreading across the formerly free world, especially in the United Kingdom.

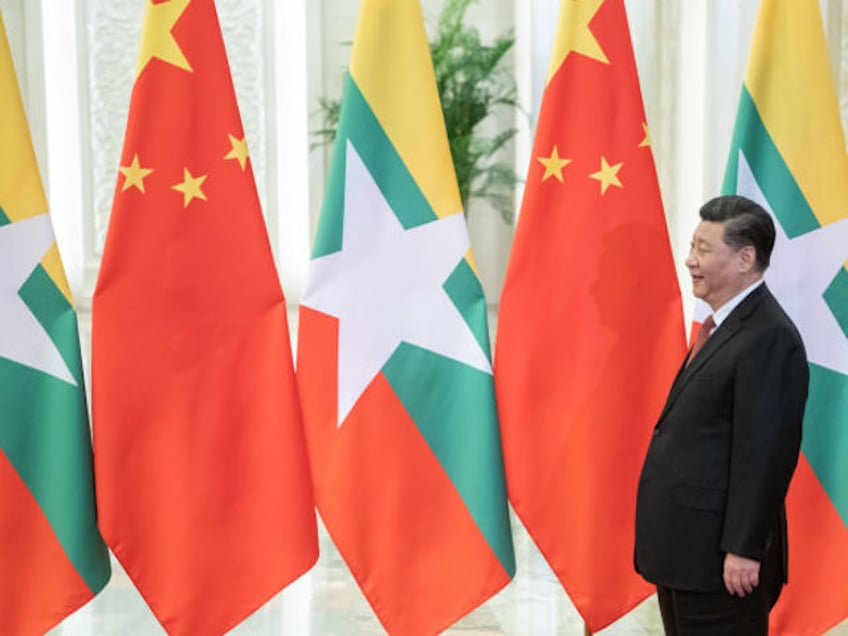

The annual “Freedom on the Net” (FOTN) report from Freedom House sadly observed that Myanmar’s military junta now rivals Communist China as “the world’s worst environment for Internet freedom.”

Military governments tend to be paranoid and regard dissent as treason, so they are quick to place restrictions on Internet access or terrorize their populations by imposing harsh penalties for “unacceptable” online speech.

Freedom House noted Myanmar’s junta excelled at both of those horrors, having both “conducted a brutally violent crackdown on dissent” and constructed a “mass censorship and surveillance regime” over the past year.

As with most other authoritarian regimes around the world, Myanmar is increasingly determined to prevent its subjects from using virtual private networks (VPNs) to bypass the regime’s Internet controls. Pakistan’s Council of Islamic Ideology announced in November that using VPN technology is contrary to Islamic sharia law, which gives Muslim governments the right to prevent the “spread of evil” by suppressing blasphemy.

Myanmar’s junta spokesperson General Zaw Min Htun speaks to the press during a ceremony to mark the country’s Armed Forces Day in Naypyidaw on March 27, 2024. (Photo by AFP)

The U.S. State Department held a meeting with civic groups and tech companies in September to discuss the war against VPNs, an essential resource for “billions of people around the world who want to access the free, open, and global Internet as we experience it in the United States.”

The State Department described VPNs as one of the few effective weapons against “digital repression” and said protecting that technology should be a high priority for all Internet freedom advocates.

Myanmar purchased much of its surveillance and censorship technology from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which continues to degrade Internet freedom beyond its borders by exporting both its authoritarian ideology and the hardware required to impose censorship. One reason freedom is declining on the Internet is that the technology to turn the virtual frontier into a dungeon has become cheaper and more powerful, bolstered by artificial intelligence (AI) tech.

China was a leader in harnessing the power of AI to turbocharge censorship. The PRC’s Internet police force is vast, and AI is a huge multiplier for the effectiveness of that force, sweeping billions of online messages for forbidden images and content.

For that matter, China’s nascent artificial intelligence systems are themselves bound in the chains of Communist ideology and speech codes from the moment of their inception. AI pioneers are concerned that censorship will become viral, as artificial intelligences build their knowledge bases from information that has been altered or restricted by Beijing and other authoritarian regimes.

A visitor interacts with a Go robot at the 2024 Global Artificial Intelligence Product Application Expo in Suzhou, China, on December 10, 2024. (Photo by Costfoto/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Freedom House pointed out that 2024 was an election year for much of the free world and election years tend to produce more repressive online environments, as governments become deeply concerned with foreign “meddling” in their elections by spreading “disinformation.”

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) noted in its own year-end review that some countries, notably including India and Pakistan, have developed a habit of sharply restricting Internet access during elections.

A good deal of that steady 14-year decline in Internet freedom can be attributed to the global War on Disinformation. Disinformation itself is also a threat to online freedom, since fraud is always a form of coercion.

Free nations are still struggling to find the right balance between respecting online freedom of speech and combating disinformation efforts and, to be brutally frank, governments do not always struggle very hard to find that balance because they have a strong tendency to classify all information that threatens the ruling party or the permanent bureaucracy as “disinformation” that must be suppressed. The search for truly fair and honest brokers of information may never end.

As grim as the news from Myanmar was, the most precipitous decline in Internet freedom charted by Freedom House in 2024 was in Kyrgyzstan under President Sadyr Japarov. Kyrgyzstan manifested every trend in global online repression simultaneously, including the government’s all-out war against opposition media websites, restrictions on Internet access by citizens, an aggressive “foreign agents” law that painted all dissident media as puppets of hostile foreign governments, and brutal retaliation against individual citizens for online speech.

The latter is a disturbing trend in declining Internet freedom, and it is hardly limited to third-world despotisms. The United Kingdom descended into dystopian horror over the past year, as citizens were frequently punished with harsh jail sentences for their social media posts. It is no longer much of a joke to say that complaining about crime in the U.K. is more likely to get you thrown in prison than committing one.

“In three-quarters of the countries covered by FOTN, Internet users faced arrest for nonviolent expression, at times leading to draconian prison sentences exceeding 10 years,” Freedom House noted.

“People were physically attacked or killed in retaliation for their online activities in a record high of at least 43 countries,” the report added.

The Diplomat noted that not a single nation in Southeast Asia achieved the minimum score of 70 out of 100 necessary to be considered “free” by Freedom House. Malaysia and the Philippines came closest with scores of 60. Most of the others scored 50 or less, with Thailand’s relentless prosecution of perceived insults to the monarchy pushing it down to 39, and Vietnam’s copy of Chinese Communist authoritarianism creeping in at 22.

Deutsche Welle (DW) quoted advocates who worried that Internet freedom could be “slipping away” in Southeast Asia, as Western tech companies bow to censorship demands from Communist, militarist, and Islamist governments. The most repressive Southeast Asian governments have informed social media platforms they will be shut down unless they obey censorship demands within a matter of hours.

“Few, if any, Southeast Asian governments even feign commitment to improving and protecting online freedoms these days. Even the region’s nominally democratic states are putting priority on online control and regulation over promoting online freedoms,” Shawn Crispin of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CJP) lamented to DW.

“For many people across Asia, the internet is the canvas for expressing their thoughts and showcasing their lives, as well as their major source for news. It is not surprising that the region’s growing number of autocratic governments are increasingly using a full gamut of technological controls to control what people see and share online,” said Phil Robertson, director of Asia Human Rights and Labor Advocates.

DW cited a recent Pew Research Center poll that found most respondents in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and Cambodia thought “social harmony” was more important than free speech, and hefty minorities felt that way in many other Southeast Asian countries, a cultural trend that makes the region highly susceptible to online repression.

In the Western world, two very sensitive issues skirted the boundary between Internet freedom and security in 2024: the move to ban China’s TikTok in the United States as a risk to both data security and social cohesion, and Australia’s aggressive move to prevent children under 16 from using social media.

Curiously, the 2024 FOTN report from Freedom House did not examine either of these issues in detail, but both are highly relevant to discussions of Internet freedom – even if one agrees that banning TikTok and keeping teens off social media are both good ideas.

Former Rep. Jamaal Bowman (NY-16) speaks at a press conference with Reps. Bowman, Pocan, Garcia, and TikTok creators at the U.S. Capitol in support of free expression on March 22, 2023 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images for TikTok)

TikTok has a large user base in the U.S. that would resent losing access to the platform, and some of them make money by generating TikTok content, so they will most assuredly feel their Internet freedom is under attack if their favorite social media service is blocked.

Likewise, critics of the push to keep children off social media argue that banning them will do more harm than good, by depriving them of access to beneficial communities and useful information. Most Australian adults in all political parties support the under-16 ban, but there is no question that a 15-year-old who awakens one morning in 2025 to find he can no longer access his preferred social media platforms will be less free than he was the day before.

Many other countries, including the United States, have taken steps to keep children off social media, although they generally aim for younger cut-off dates than Australia. The issue is part of a much larger international debate about the rights of children and their ages of consent for various activities, and those questions have become more difficult as constant access to the Internet through mobile devices becomes a fixture of childhood.

The 2024 FOTN report concluded with a set of policy recommendations, and the top one from Freedom House was for governments around the world to “promote freedom of expression and access to information.” It is far too difficult, at the dawn of 2025, to find governments that wholeheartedly wish to do that.