The South China Morning Post (SCMP) reported on Monday that a growing number of “private” Chinese companies are interested in buying censorship artificial intelligence (AI) from the state-run People’s Daily.

One of the main reasons for this interest is that even the smallest deviation from the Chinese Communist Party’s totalitarian speech codes can mean huge fines for a corporation. A fully-trained A.I. commissar that can scan thousands of images, social media posts, and web pages for forbidden content — even something as minor as “the unintended inclusion of a disgraced official in a picture” — that might get a company fined or shut down could save the companies major fines or worse.

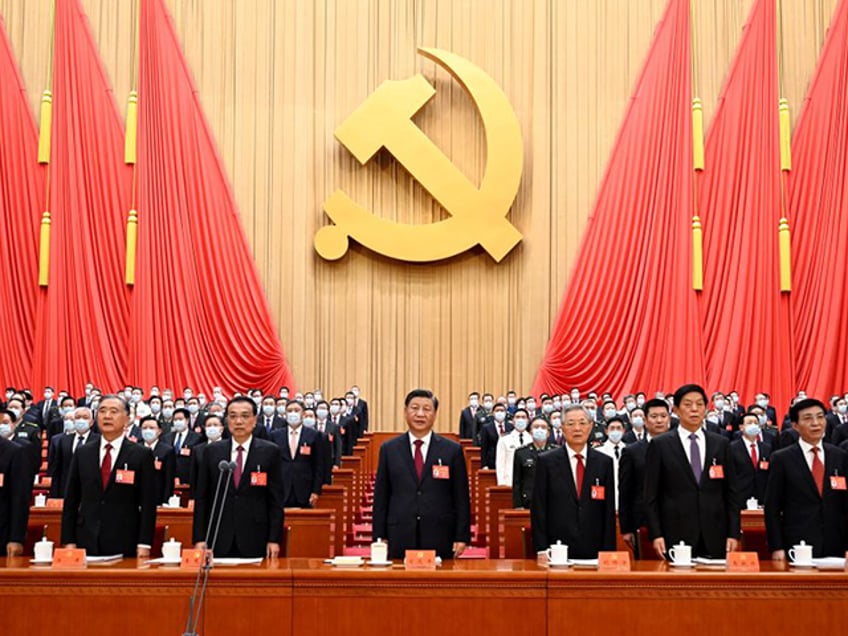

Opening session of the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. (Li Xueren/Xinhua via Getty Images)

“To make matters worse, perceived offenders can be boycotted by angry internet users. The online community is also policed by nationalistic voices and even business competitors looking for the chance to torpedo a rival,” the SCMP noted.

The People’s Daily is leasing a “content moderation” system called Renmin Shenjiao that was launched last July. The name of the system translates to “People’s Proofreading.” It ostensibly uses a combination of A.I. algorithms and human censors to spot politically troublesome content in “written materials, photos, videos, and posts on social media platforms, including WeChat and Weibo.”

Since the People’s Daily is the chief media organ of the Chinese Communist Party, customers can rest assured Renmin Shenjiao has been updated with the latest speech codes, propaganda requirements, and lists of disfavored officials who are not supposed to be mentioned anymore. Renmin Shenjiao staff “may have knowledge of new taboos that were otherwise not known to the public,” according to one insider.

The service costs between $6,400 and $13,700 per year, depending on the volume of material produced by the customer. Clients proceed to upload all of their photos and writing to a website where the AI and human censors can screen it for “material related to ideology, religion, purged government officials, Chinese dissidents, and maps related to disputed border areas.”

“According to the sales document, animations of government leaders, content related to their relatives, and references to disgraced celebrities would also be picked up as potential risks,” the SCMP added.

Renmin Shenjiao is not the only name in China’s outsourced censorship market. The SCMP noted its own owner, Alibaba, and rival tech giant Tencent both provide “content moderation” services for their cloud services clients and Tencent’s is sophisticated enough to scan live streams for speech code violations.

“Companies that want to maximize profit will rationally acquire content moderation services that minimize the risk of overstepping political boundaries or being out of sync with Xi Jinping Thought,” suggested Asia Society Policy Institute fellow Neil Thomas.

“Xi Jinping Thought” is a collective name for the policies and philosophy of China’s current dictator, who styles himself as the most important leader since Mao Zedong, and possibly even more important than Mao himself.

Xi Jinping Thought is required reading at every level of Chinese education and China’s ally Russia recently created the first foreign institution dedicated to studying Xi’s ideology. In March, the Chinese Communist Party formally replaced Maoism, Leninism, and even Marxism with Xi Jinping Thought as the foundational ideology for its rulebook.

Since even the smallest and most inadvertent transgression against Xi Jinping Thought can destroy a company or a career, analysts felt it was only a matter of time before individual users begin paying for outsourced content moderation to protect themselves — and there is no reason to think foreign companies doing business in China would not follow suit, especially since the regime in Beijing has a track record of punishing foreign companies for speech code infractions.

Chinese Communist Party internet regulators have been busy lately. In early July, two online media outlets were suspended without warning or explanation. One of them was a healthcare news service that filed some critical reports during the Wuhan coronavirus pandemic.

On Monday, a popular Chinese economic blogger named Wu Xiaobo was blacklisted from social media because he expressed pessimism about the economy. Several other commentators with smaller followings have been suspended recently for the same reason.