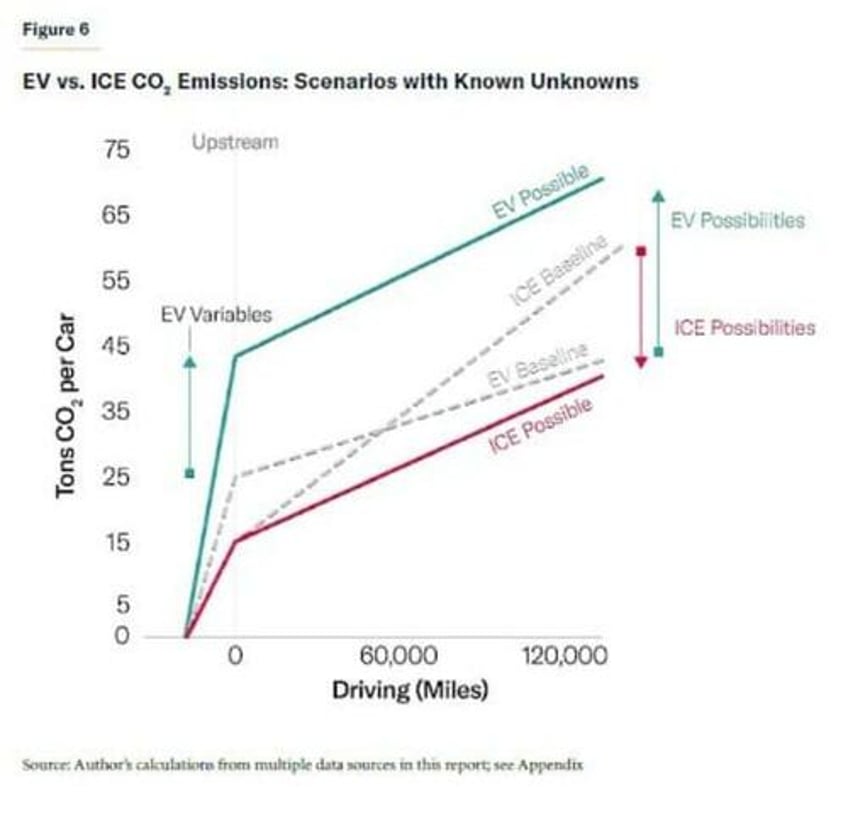

A new study from the Manhattan Institute concluded that certain EVs emit more greenhouse gas emissions over their lifetime than certain ICE vehicles.

According to the report, the possibilities of GHG emissions for EVs is much wider than for ICEs.

In base case scenarios, EVs start off as having more emissions mainly due to the energy intensity of the EV and battery metals used in their manufacture but eventually catch up to ICEs around the 60,000 driven miles mark.

Electric vehicle skeptics have frequently argued that the manufacturing and disposal of battery-electric vehicles like Teslas as well as reliance on coal to generate the electricity that powers them leaves EVs with a larger carbon footprint than nonelectric vehicles. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of studies that have tried to approve or disapprove this notion. But finally, the Manhattan Institute has compiled a comprehensive report that compares lifetime greenhouse gas emissions of EVs vs. ICEs by looking at dozens of parameters and data points.

According to the report, the possibilities of GHG emissions for EVs is much wider than for ICEs mainly due to the much wider variances in upstream (mining+ manufacturing) emissions by EVs. The differences are such that the dirtiest EVs can have more than double the emissions of the cleanest internal combustion engines.

Source: Manhattan Institute

However, you will note that in base-case scenarios, EVs start off as having more emissions mainly due to the energy intensity of the EV and battery metals used in their manufacture but eventually catch up to EVs around the 60,000 driven miles mark.

Several universities and trade organizations have previously conducted life cycle analyses that compare the amount of greenhouse gasses created from the production, use and disposal of a B.E.V. vs. gasoline-powered vehicles of comparable size.

Vehicle emissions are divided into two general categories: air pollutants, which contribute to health problems and greenhouse gasses (GHGs), such as carbon dioxide and methane. Both categories of emissions are frequently evaluated on a tailpipe basis, a well-to-wheel basis, and a cradle-to-grave basis. Well-to-wheel emissions are emissions related to fuel production, processing, distribution and use while cradle-to-grave emissions include well-to-wheel emissions as well as vehicle-cycle emissions associated with vehicle and battery manufacturing, recycling, and disposal.

The good news: whereas these studies have arrived at varying emission figures, they have invariably found that the greenhouse-gas emission difference caused by the carbon-intensive production of BEVs vs. ICE vehicles is virtually erased in the first few years of an EVs life.

In one such study conducted by the University of Michigan, it takes 1.4 to 1.5 years for EV sedans to erase the pollution advantage of ICE vehicles due to the manufacturing process; 1.6 to 1.9 years for S.U.V.s and about 1.6 years for pickup trucks. These numbers are based on the average number of vehicle miles driven in the United States.

According to the study, on average, emissions from B.E.V. sedans are ~35% of the emissions from an internal-combustion sedan; electric S.U.V.s produce ~37% of the emissions of a gasoline-powered vehicle while B.E.V. pickups create ~34% of the emissions of an internal combustion model. All-electric vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), and hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs, which operate as EVs for limited distances), produce lower tailpipe emissions than ICE vehicles, and zero tailpipe emissions when they run only on electricity.

Electricity Generation

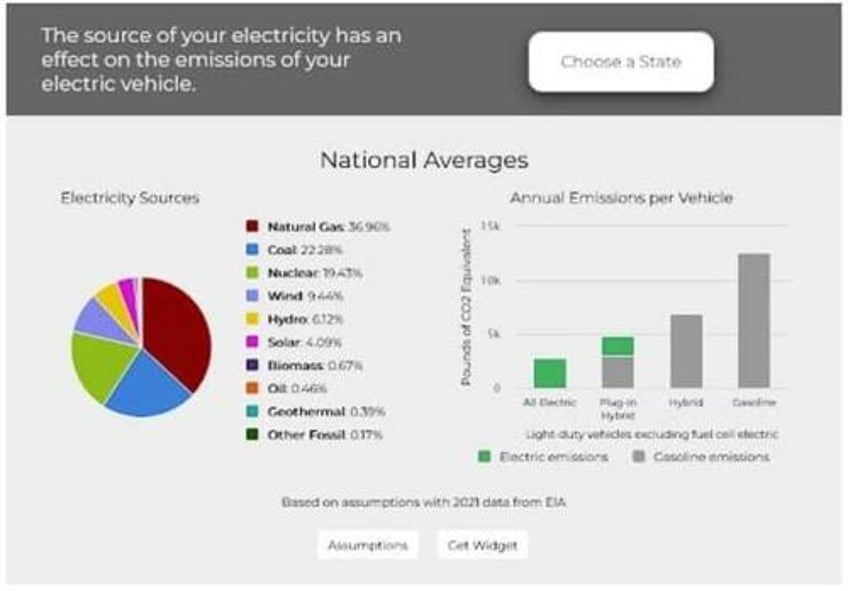

Even though all-electric vehicles as well as PHEVs running only on electricity produce zero tailpipe emissions, electricity production may generate emissions depending on how the electricity is generated.

According to Greg Keoleian, director of the Center for Sustainable Systems at the University of Michigan, 78 of the 3,143 counties in the United States actually have more emissions from electric sedans than from internal combustion vehicles because they generate most of their electricity by burning coal.

But overall, electric vehicles are much kinder on the environment than ICEs.

According to the U.S. Department Of Energy, the average all-electric vehicle in the U.S. produces 2,817 pounds of CO2 equivalent per year; plug-in hybrids emit 4,824 pounds of CO2 equivalent, hybrid vehicles generate 6,898 pounds while gasoline-powered vehicles produce 12,594 pounds of CO2 equivalent per year.

Source: U.S. Department Of Energy

Direct Lithium Extraction

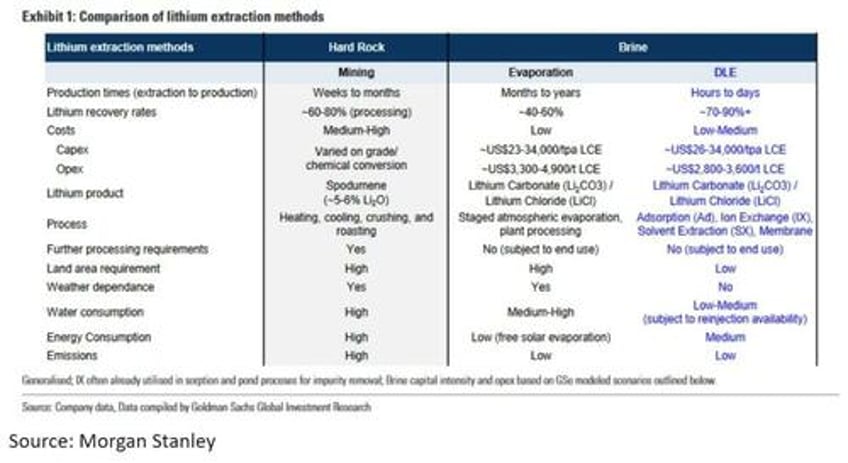

The Manhattan Institute report points at the high upstream emissions of EVs as a key reason why EVs could end up doing more harm to the environment. But an upcoming technology could rapidly improve the score for EVs: direct lithium extraction.

Over the past few years, the lithium markets exploded as the electrification drive went into overdrive. EV makers like Tesla Inc. (NASDAQ:TSLA) have been scrambling to secure supplies amid rapid EV growth and tight lithium supplies, sending lithium carbonate prices up more than six-fold and spodumene up nearly tenfold in the space of a few years.

But a new lithium extraction technology could change the lithium industry forever and significantly increase the supply of lithium from brine projects, much like shale technology did for oil.

A fleet of direct lithium extraction (DLE) technologies are getting ready to tap salty brine deposits across North America, Europe, Asia and elsewhere, with the U.S. Geological Survey estimating the technology could unlock 70% of global reserves of the metal. Whereas DLE technologies vary, they are generally comparable to common household water softeners, and aim to extract ~90% of lithium in brine water vs. 50% using conventional ponds.

Their biggest draw: they can supply lithium for EV batteries literally in a matter of hours or days, way faster than 12-18 months needed to be filtered through in order to be able to extract lithium carbonate from water-intensive evaporation ponds and open-pit mines.

DLE also comes with the added bonus of offering ESG/sustainability benefits: DLE technologies are portable, able to recycle much of their fresh water and limit hydrochloric acid use.

"The world needs abundant, low-cost lithium to have an energy transition, and DLE has the potential to meet that goal," Ken Hoffman, co-head of the EV Battery Materials Research group at McKinsey & Co., has told Reuters.

"The industry is so close to a major leap forward," John Burba, who helped invent a prominent DLE technology and is IBAT's executive chairman, has told Reuters.

The DLE industry is expected to grow to more than $10 billion in annual revenue within the next decade.

Source: Morgan Stanley

Commercial scale DLE projects are expected to start coming online in 2025, and could supply 13% of global lithium supply by 2030, as per projections by Fastmarkets.