We covered some of the most important topics in last weekend’s A Million Things to Parse. From DOGE, to Ukraine/Russia, to tariffs, to the so-called Mar-a-Lago Accord, much of what is shaping the global landscape is coming out of D.C. (though the Trump administration seems to be doing a lot of it out of Mar-a-Lago). Academy also wound up being quoted in the FT – Musk and markets: why DOGE is not cutting through, and in Barron’s Up & Down Wall Street.

Clearly the topics are resonating as investors and corporations try to navigate these times. With another week of headlines behind us, we should be closer to “knowing” the answers, but I’m not sure that is the case. As we look at so many issues, it is possible to see a “successful” path where negotiations and actions occur, leaving the economy and markets in a much better spot. It is also possible to see this playing out in a way that leads us to a much worse economy and weaker markets. And in between those two “binary” options, there are a lot of other possibilities.

Here is what I think we can add to last weekend’s report along with an update on how we are trying to interpret the policies and likely outcomes.

Re-Trading Is Worrisome

In capital markets a “deal is a deal.” You really cannot go back and change the terms later, and certainly not unilaterally. For much of my career I traded bonds and credit derivatives. You agreed on price and size and moved on. Occasionally you had trade disputes, but it was rare. But sometimes traders developed the reputation of being “flaky.” They didn’t live up to their word. Very few people who developed that reputation went on to thrive.

I think this is important because I cannot help but characterize two things as “re-trading:”

Making Ukraine pay for things already given seems like re-trading to me. Whether or not we liked how aid to Ukraine was given, it was done legally (as far as I know). Does this mean that every time the U.S. does something, we can later go back and retroactively say that the terms aren’t what you thought? How will countries engage with the U.S. when a deal might not be a deal?

Raising new tariffs on Canada and Mexico, while the USMCA, which was implemented under the first Trump term, is still in place, seems a bit odd as well. Not alarming and well within the president’s rights, but still…

Part of the Mar-a-Lago Accord chatter is around forcing countries to buy or convert Treasury holdings into zero-coupon bonds that cannot be traded. The argument is that countries need to pay for the security that the U.S. provides and has provided. Some of the logic makes sense. The U.S. spends a lot of money and protects the world’s supply chains. The U.S. benefits as do other countries. It may even be a reasonable ask to get paid for undertaking that role going forward. But, from the chatter I’m hearing and seeing, there is an element that the countries need to pay for what was already provided. How will that affect countries dealing with the U.S. in the future, if in the back of their minds, they are concerned that they will get coerced into something?

If countries bulk up their own defenses, they will have less need for this in the future (European Defense stocks have done incredibly well of late, in anticipation of such spending).

If countries have to pay for something, maybe they would rather fund their own protection forces, rather than paying the U.S. That could reduce the U.S. need to spend but it would come with a cost of a reduced presence globally. Also, will the U.S. really cut back on protection if countries don’t agree? Is the protection other countries get something that can be trimmed out of the U.S. budget, or is it something that occurs by the U.S. protecting its own interests?

Re-trading is not good policy and could lead to countries looking for alternatives to the U.S. and hasten deglobalization, which would not be good for American companies. The S&P 500 is up 2% YTD, while most of Europe is up more than 10% and the Hang Seng is up 17%.

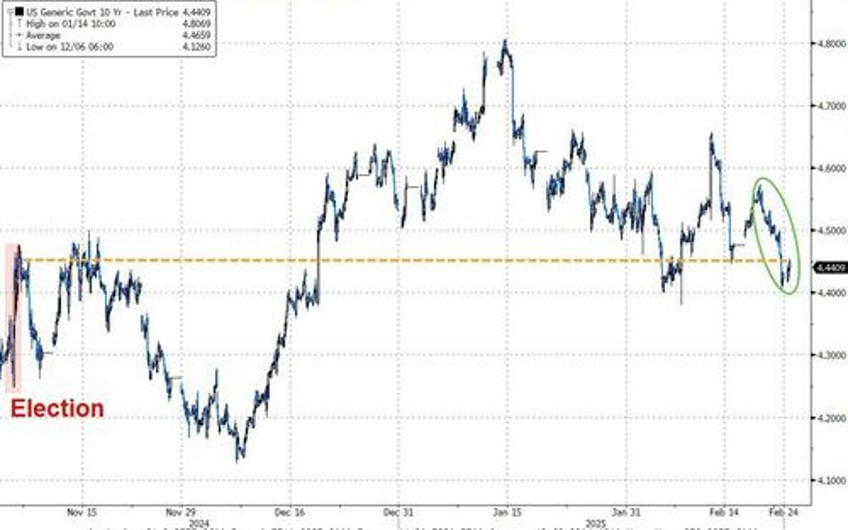

The Focus on 10-Year Yields

This administration, at many levels, has made it clear that when they focus on getting lower interest rates, it is across the curve. They aren’t just worried about a Fed cut here or there; they want the 10- year yield much lower.

Markets have liked that and there are things that are working in their favor, in a positive way:

Just talking about it can help. While the Fed, through its transparency, has lost some of its ability to jawbone markets, the president and Treasury Secretary have that ability. The “promise” to not extend the duration of the balance sheet did help bonds.

QE will be ending (though since QE was almost exclusively achieved by allowing debt to mature, I’m not sure that will help that much).

Can DOGE deliver on the deficit? Will tariffs help the deficit? There seems to be some progress on the DOGE front, but it really is at the early stages. Will other policy announcements (like tax cuts) undo any deficit savings?

4.4% on the 10-year now seems too low, especially given many of the reasons for the recent price action (in the face of higher-than-expected inflation data – which I think is suspect and subject to bad seasonality adjustments).

The one thing that is concerning is that yields are justified if the economy isn’t that strong!

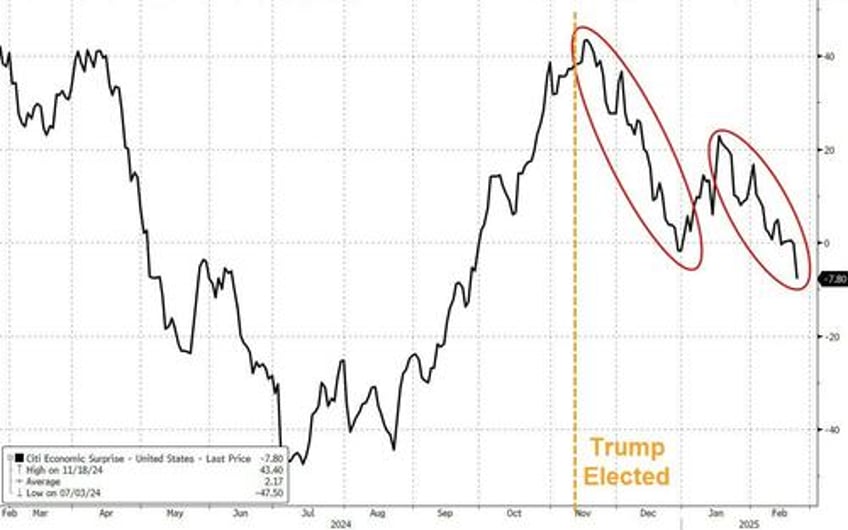

Economic Weakness

Service PMI came in below 50. Not good.

We have argued that seasonal adjustments to the jobs data are incorrect and have overstated jobs in the first part of the year. While that effect is diminishing over time, it is still real, and we could see some job losses.

We have no idea (yet) what the economic implications are from the DOGE cuts so far. If it is all “fat” and excess spending, great. However, to the extent it was important and feeding into the economy, we could see some reverberations in the coming months.

Without a doubt, laying off government employees will affect the economy (with the D.C. area being hardest hit). But how easy is it to find jobs in the market? I think the JOLTS Quit Rate tells us that it is not so easy (and certainly not as easy as you might be led to believe by the NFP prints).

Look for further signs of economic slowdowns here and the ongoing reversal of the American Exceptionalism trade. I think yields should be higher but I am rethinking that as my concern about the state of the economy evolves. We’ve discussed increasing delinquencies in prior T-Reports, and updated data on that front is doing nothing to assuage our concerns.

Optimal Supply Chains

We mentioned that we see the potential for some very good outcomes from what is being strategized in Mar-a-Lago and D.C. Having said that, even if we get to some really positive outcome (which is not my base case), there will be hiccups along the way.

If you believe, and it seems reasonable, that most companies have designed efficient supply chains given the existing rules, then the changes made to deal with new rules will be suboptimal.

Any behavior changes in response to new rules (or even the threat of new rules) has to be negative for companies and the economy (if the existing world is optimal).

There is so much uncertainty. We are halfway through the 30-day stay of execution on the initial Mexican and Canadian tariffs, with little insight into what will happen when the first reprieve expires.

Start looking for “problems” or signs that the uncertainty is hurting the global economy, which will impact the U.S. and our markets the most.

Bottom Line

I am forced to lower my target on the 10-year yield (for the wrong reasons). We’ve been looking for 4.8% or higher, but now 4.6% seems reasonable given what the government can do. That rate level assumes a decent economy, which I’m increasingly worried is too optimistic. Expect 2 rate cuts this year, 1 in May and 1 in autumn, but even with inflation expectations rising, the number of cuts might need to be higher, as disruptions to the global economy and further (potentially rapid) deglobalization is creeping its way up the league table in our list of probable outcomes.

On equities, I continue to look for trades that will benefit from National Security = National Production. We have been overallocated to Chinese stocks and that has been great. We have been very concerned about the Nasdaq 100 and continue to think that the risk of a 10% or greater pullback is high. A pullback to pre-election levels would be close to 10% from here and given what we are seeing in the economy and economic policy so far, that is now my target. Basically an “unwind” of the gains made since the election as so far policy has done little to convince me that those gains are warranted.

Credit spreads should widen in sympathy with equities, but I’m still not particularly concerned (though, again, this is dependent on a decent economy, which might not be the case).

It is difficult to believe that we are “only” one month into Trump 2.0 given the sheer number of headlines we have been forced to digest, but the picture isn’t much clearer to me than it was before he was sworn in, and that makes me nervous for the economy and markets.