The biggest medium-term risk for bonds is not from buyers demanding a lower price, but from multi-asset managers who see little need for holding much government debt at all, at any price.

Bond vigilantes are back in the spotlight.

The surge in US and global yields to the highest in more than a decade has prompted speculation that investors are seeking greater compensation to hold government debt as the inflation rate remains elevated and fiscal deficits swell.

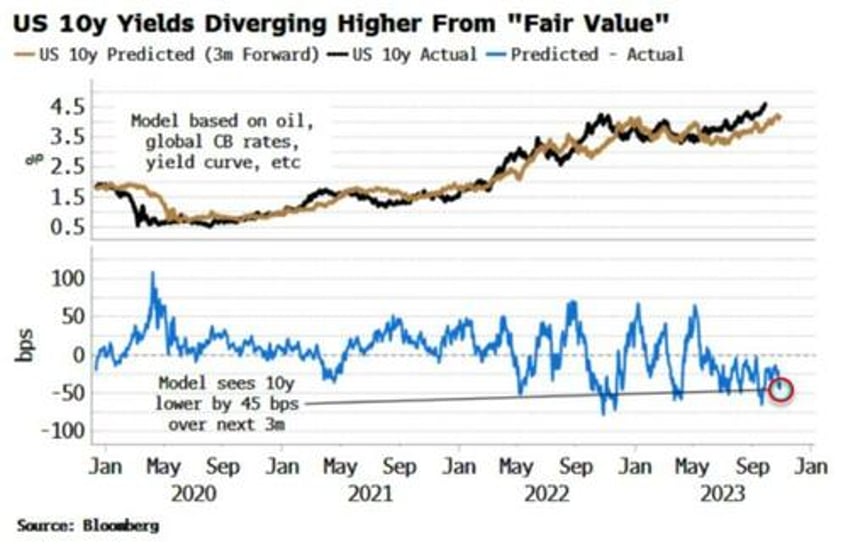

Treasury yields are decoupling from usually reliable underlying drivers, such as the strength of manufacturing or the price ratio of copper to gold.

It’s the same thing with a fair value model that factors in oil, central-bank rates and the shape of the yield curve.

US 10-year yields at around 4.7% are now almost 50 basis points above the model’s value.

Term premium — essentially the difference between the yield and the expected short-term rate — has begun to accelerate higher, and is back to being positive in the US, pushing the yield curve steeper.

On longer-term bonds, term premium has been in secular decline over most of the last four decades, initially as inflation expectations were re-anchored after the stagflation of the 1970s.

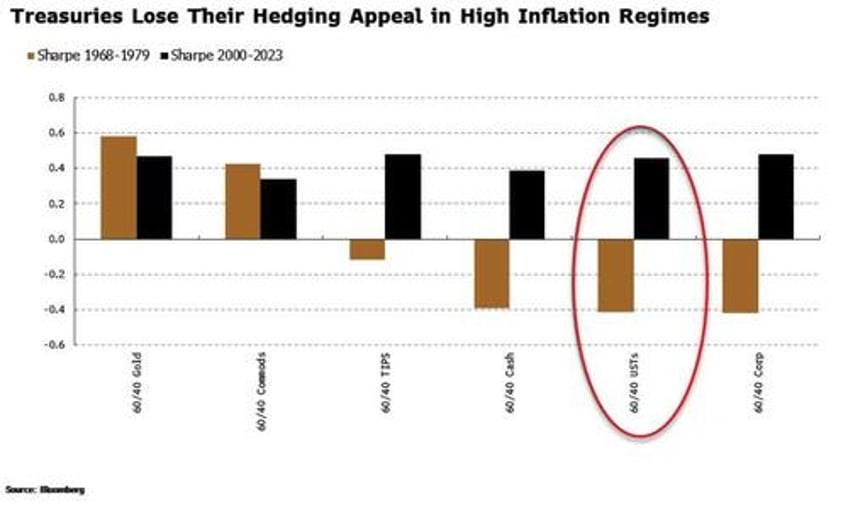

It continued to fall as contained inflation flipped the stock-bond correlation to negative, making Treasuries an attractive hedge for stocks – through dampening portfolio volatility and increasing risk-adjusted returns – while also acting as a recession hedge.

Term premium was further depressed by quantitative easing.

But in today’s elevated inflation regime, the stock-bond correlation is positive again.

Treasuries are losing their efficacy as a portfolio hedge.

And their usefulness as a recession hedge is on shakier ground, as the next growth shock could quite conceivably be accompanied by an inflation shock, with stocks and bonds falling together.

Over the last 20 years or so, the traditional 60/40-like portfolio — one that allocates 60% of money to stocks and 40% to bonds — has delivered positive risk-adjusted returns on a par with similar approaches using assets like commodities or gold instead of bonds.

But in the 1970s’ inflation regime, a 60/40 strategy with Treasuries did very poorly, both outright and versus other 60/40 portfolios.

Portfolios using the 60/40 approach, vol-targeting and risk-parity strategies own hundreds of billions if not trillions of dollars in Treasuries.

But if the very reasons for owning them – their portfolio-smoothing properties and recession protection – can no longer be taken for granted, managers may question owning many of them at all, no matter what the price.

In a world of high cash rates, owning more equities may end up looking more attractive – the return of TINA (There Is No Alternative), but with a vengeance (however ill-advised that may be).

There will always be demand for government debt, from households, banks and liability-matchers. But for a large constituency, owning USTs is a choice.

With non-believers, there’s no need for vigilantism, just a swift exit past the pews and out of the church of bonds – and even higher yields as a consequence.