By Dhaval Joshi of BCA Research

Many economists and strategists emphasize the importance of China’s credit impulse as the driver of China’s – and the world’s – economic growth. A key question for them is: what is happening to China’s credit impulse – is it increasing, decreasing, stabilizing, or destabilizing? For many years, this was indeed the key question to ask.

Not anymore.

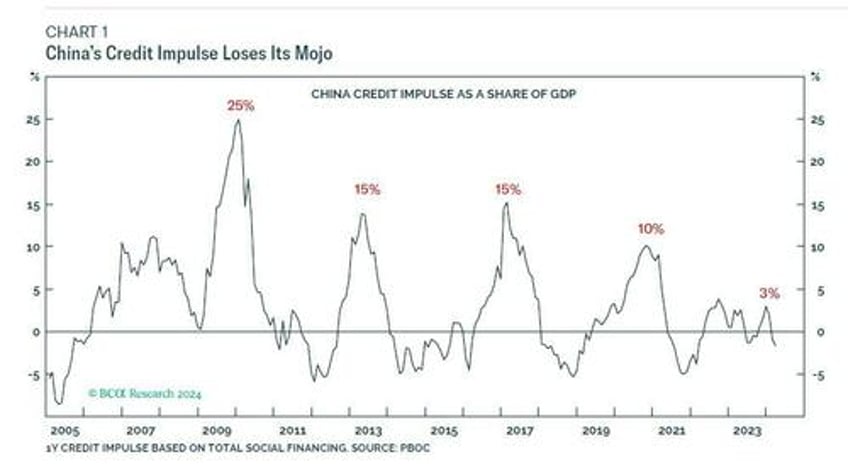

After the global financial crisis of 2008-09, China unleashed a stimulus bazooka. A stimulus so big that China’s credit impulse peaked at a massive and unprecedented 25% of China’s GDP. In the subsequent stimuluses of 2013 and 2017, China’s credit impulse peaked at a sizable, albeit lower, 15% of GDP. Then in 2020 came the global pandemic. Yet even after this once-in-

a-century shock, China’s credit impulse peaked at a still-lower 10 percent of GDP, less than half of the post-GFC peak.

In the so-called ‘stimulus’ that has come more recently, the impact has truly dwindled. China’s credit impulse has peaked at little more than 3 percent of GDP, equating to barely a tenth of the post-GFC impact (Chart 1).

Of course, China is a bigger part of the world economy now than it was during the global financial crisis. Nevertheless, a peak stimulus of 25% of China’s GDP in 2009 equaled 2% of the world economy. Whereas a peak stimulus of 3% of China’s GDP today equals less than 0.5 percent of the world economy. It follows that China’s credit impulse is becoming less relevant, both for its own economy and for the world economy.

Exponential Credit Growth Fueled China’s Boom

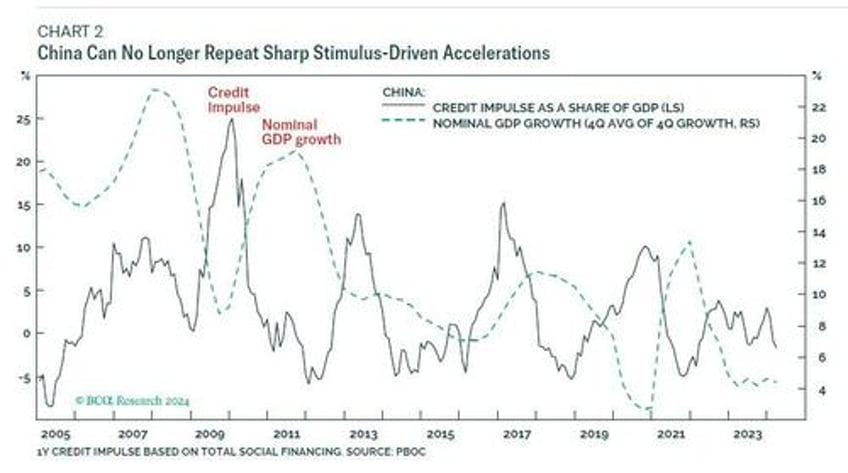

China’s peak credit impulse mattered a lot because, as might be expected, China’s nominal GDP growth accelerated by a commensurate amount to the associated peak credit impulse. A peak credit impulse that was well into double digits would cause nominal growth to accelerate by double digits. But with a peak impulse that has now dwindled into the low single-digits, China can no longer repeat such sharp stimulus-driven accelerations (Chart 2).

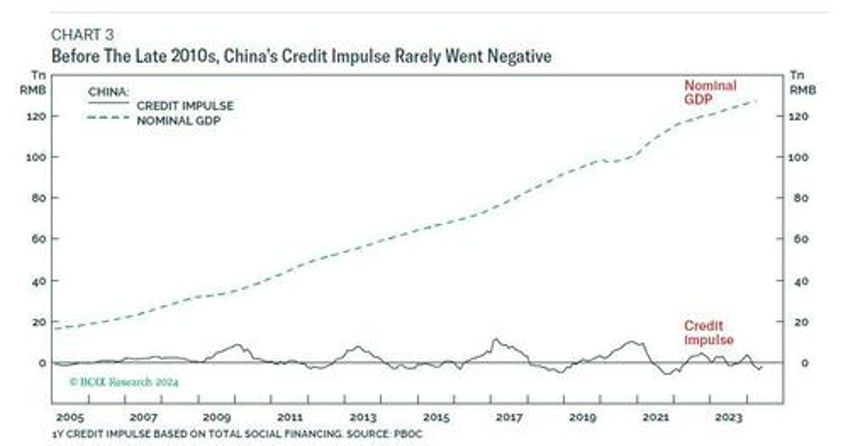

China’s credit impulse also mattered because, until the late-2010s, it rarely went negative (Chart 3). Meaning it was almost always a tailwind to growth, and almost never a headwind. Given that the credit impulse is the change in the change in credit, this raises an interesting question. If the second derivative of the curve is always positive, then what is the underlying curve? Any schoolboy mathematician will tell you the answer is an exponential curve. In fact, the very definition of an exponential curve is that all its derivatives must be positive.

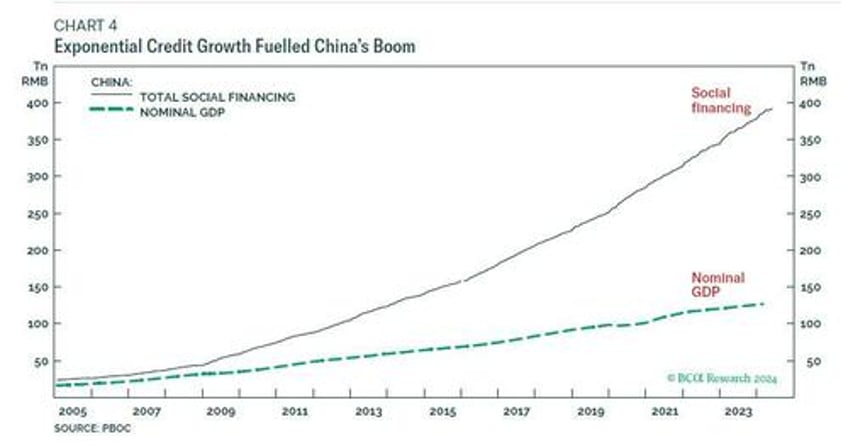

Guess what? China’s stock of credit was an exponential curve. In fact, we can describe it as exponential-plus because, until the mid-2010s, it looked exponential even on a logarithmic scale! There, in a nutshell is the recipe for China’s spectacular growth of the past few decades: exponential credit growth (Chart 4).

The trouble is that exponential credit growth cannot last forever because credit must be put to productive use, and credit cannot be put to productive use exponentially.

Absent China’s Exponential Credit Growth, World Growth Will Slow To Sub-3 Percent

For several decades, China’s exponential credit growth funded a housing and construction boom that fulfilled Chinese households’ insatiable demand for investment properties.

Without a comprehensive pension or welfare system, Chinese households save a lot. It was rational to channel those savings into the double-digit gains coming from investment properties. Once those double-digit gains became seemingly risk-free, it was also ‘rational’ not to require a rental yield.

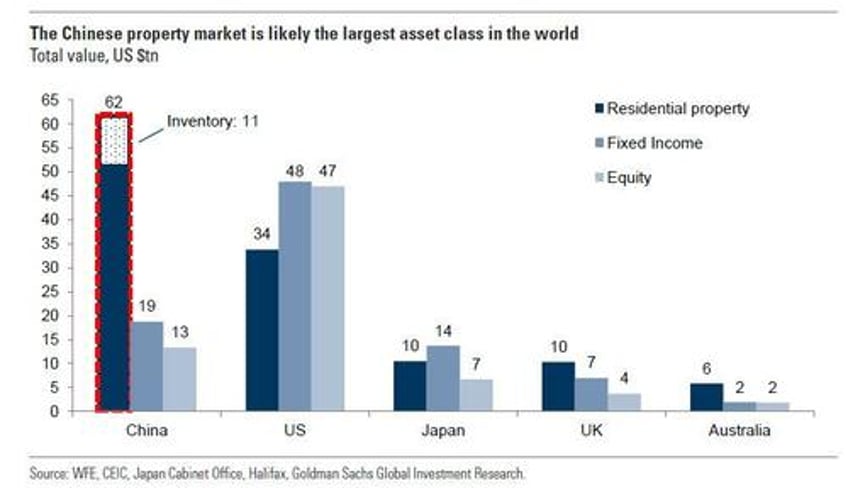

The result: house price-to-rent ratios, at 75, that dwarfed even the peak bubble valuations in Japan, Spain, and Australia; a Chinese real estate market valued at $100 trillion, making it by far the largest asset class in the world; plus 130 million empty Chinese homes – a stock of unoccupied investment properties equal to the entire housing stock of the United States.

But with Chinese house prices falling for two years now, the illusion of risk-free property investment has been shattered, and investment property demand has collapsed. China’s command economy will ensure that its housing market adjustment comes from a reduction in housing development and construction activity to equilibrate supply with collapsing demand. Yet this carries huge implications for the world economy – because China’s construction and infrastructure boom, fuelled by exponential credit growth, was the world’s main growth engine.

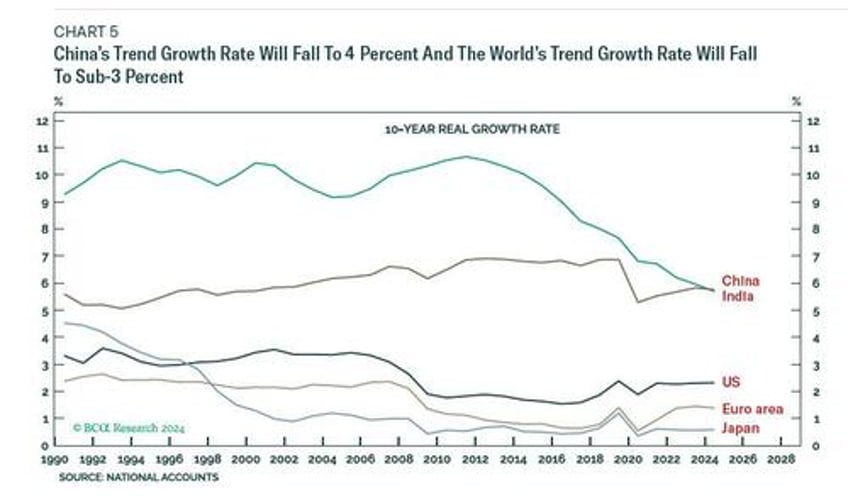

Absent exponential credit growth, China’s trend growth rate will fall to 4 percent and the world’s trend growth rate will fall to sub-3 percent (Chart 5).

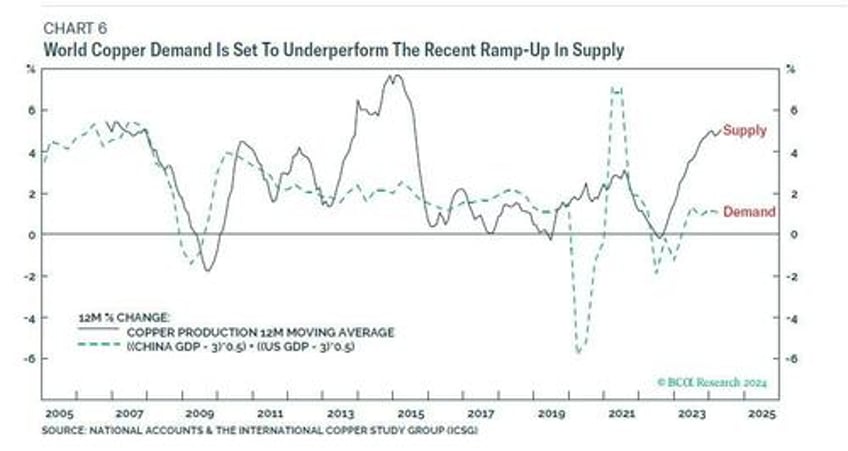

One important consequence will be for commodity demand, and there is a subtle point that most people do not grasp. Commodity demand growth tracks economic growth less a deflator for efficiency gains. For copper, the efficiency deflator is around 3 percent a year. Hence, as the world’s trend growth falls to sub-3 percent, the trend growth in copper demand will flip from positive to negative.

The perma-bulls point to new sources of copper demand that will come from the de-carbonisation of the world economy. Yet they ignore that the main engine of existing demand is dying. With new demand, at best, just substituting for this dying demand, world copper demand is set to underperform the recent ramp-up in supply (Chart 6).

Three Investment Conclusions, One Provocative

The first conclusion is that absent China’s exponential credit growth, it will be impossible to have a so-called ‘commodity super-cycle’. Instead, commodities will now follow shorter sharper cycles. Right now, as we presaged in early-May, industrial metals are unwinding the sharp tactical rally that began this year. This we are playing with a tactical short in the global base metals ETF (XBM).

The second conclusion is that absent China’s exponential credit growth, it will be difficult for China’s stock market to produce long-lasting rallies. Like commodities, the CSI 300 will now be a tactical play.

Following a protracted sell-off during 2023, we anticipated that the CSI 300 was ripe for a sharp countertrend rally earlier this year. However, the collapsed 65-day complexity of this sharp rally implies that it is now exhausted.

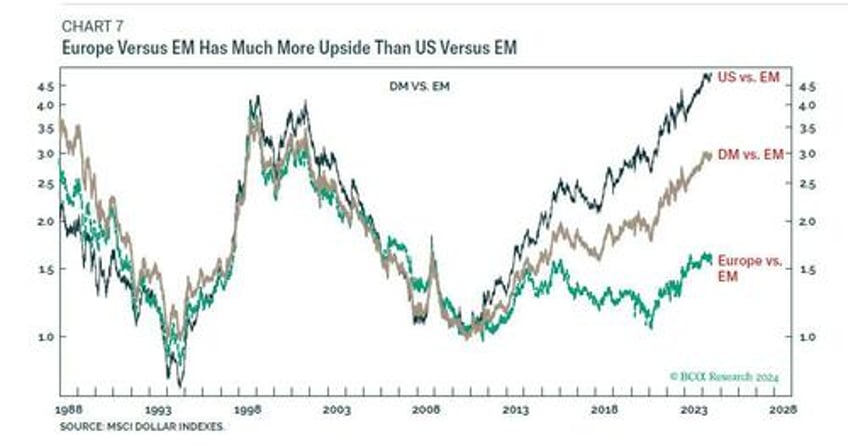

The third conclusion concerns our structural overweight in developed markets (DM) versus emerging markets (EM) which has returned 50 percent since initiation in late-2020. The end of China’s exponential credit growth might suggest a continuation of DM’s outperformance, but we must weigh this against the bubble-like valuations of the dominant US superstar stocks which I highlighted in BCA Research - Who Will Find Gold In The AI Gold Rush, And When?

Given that the outperformance of the US versus EM is at top of its multi-decade channel, while the outperformance of Europe versus EM is still below the middle of this channel, it is time to modify our structural overweight to DM versus EM (Chart 7).

Close overweight DM versus EM. And replace with overweight Europe versus EM.