Credit spreads, high yield and investment grade, are the major assets least reflecting a recession based on their behavior before previous downturns, with stocks not far behind.

Recession talk has gone out of fashion, replaced by soft-landing chatter (yesterday’s weaker-than-expected JOLTS and consumer data just released might help change that though).

But the underlying data has not changed significantly enough that we can all go back to sleep, ready to be awoken by the next boom.

Manufacturing is in recession, and services are turning down, based on both the ISM and PMI surveys.

At their current rate of decline, each survey will be under the 50 contractionary level very soon.

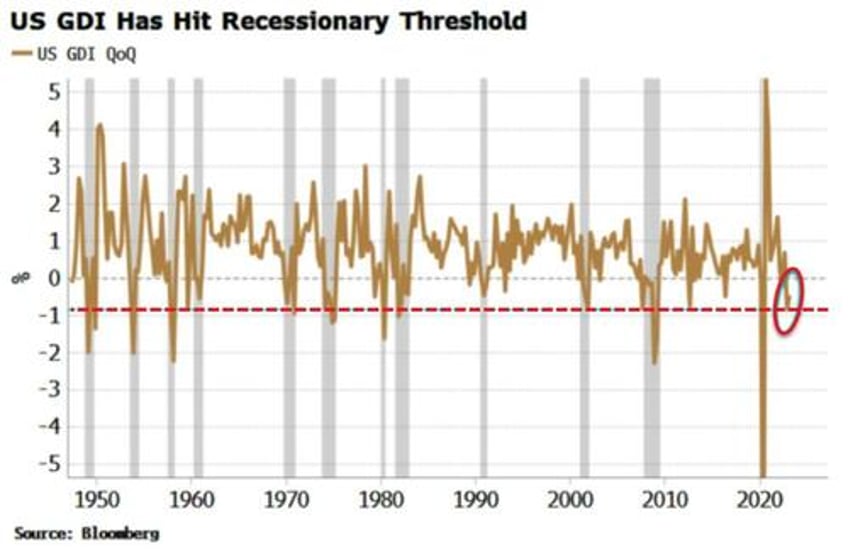

GDI – gross domestic income – is consistent with a recession. Further, GDP and GDI have shown the largest discrepancy in over 20 years, with the average of the two close to 0%.

Moreover, my Recession Gauge – which captures when a whole swathe of economic and market data start to look recessionary at the same time – has been indicating a recession all year. Also, unemployment and continuing claims by US state are consistent with a near-term recession.

The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow is one of the most positive indicators, currently expecting 3Q23 annualized real GDP to be 5.9%. But it’s worth noting that in its short 12-year history it has never been tested in a (non-pandemic) recession – precisely when data is often most wrong and has to be significantly revised.

Recessions tend not to happen gradually, bur precipitately.

Hence the relative economic calm should not be taken as a sign to become less vigilant. That is doubly the case now when most assets are pricing in a low probability of a recession.

Credit is the asset class most untroubled by recession risks, with global and US equities not far behind (based on each asset’s behaviour around previous recessions). As I discussed yesterday, credit spreads are already very divergent to the burgeoning number of bankruptcy filings in the US.

In this sort of environment, the costs of hedging recession risk are cheap(er) precisely because the risk has gone off most people’s radar.

Thus even if the economy manages to skirt a slump, the opportunity cost of insuring against one is relatively low - unless of course risk takes off again, but liquidity conditions are becoming less conducive to that happening.