Sovereign yields in China have been falling in recent months, in marked contrast to almost every other major country. This is a key macro variable to watch for signs China is ready to ease policy more comprehensively as its tolerance is tested for an economy that is becoming increasingly deflationary. Further, vigilance should be increased for a yuan devaluation. Though not a base case, the tail-risk of one occurring is rising.

Year of the Dragon in China it may be, but the economy has yet to exhibit the abundance of energy and enthusiasm those born under the symbol are supposed to possess. China failed to exit the pandemic with the resurgence in growth seen in many other countries, and the outlook has been lackluster ever since.

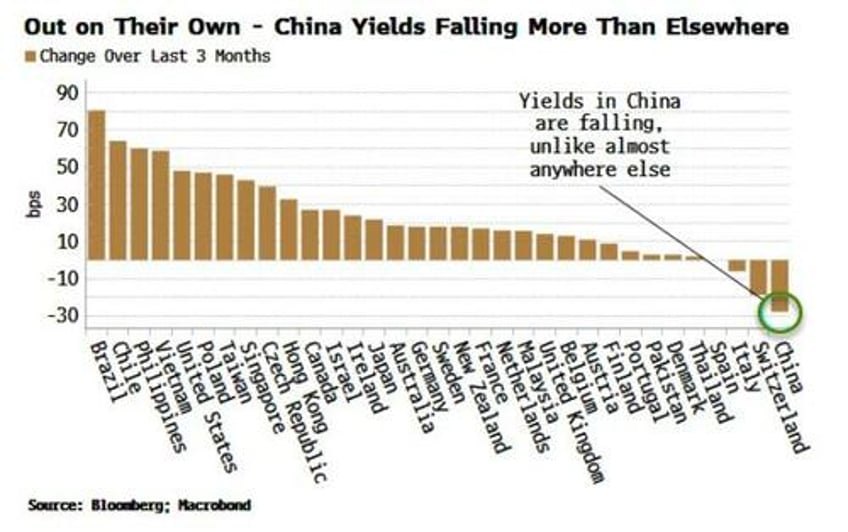

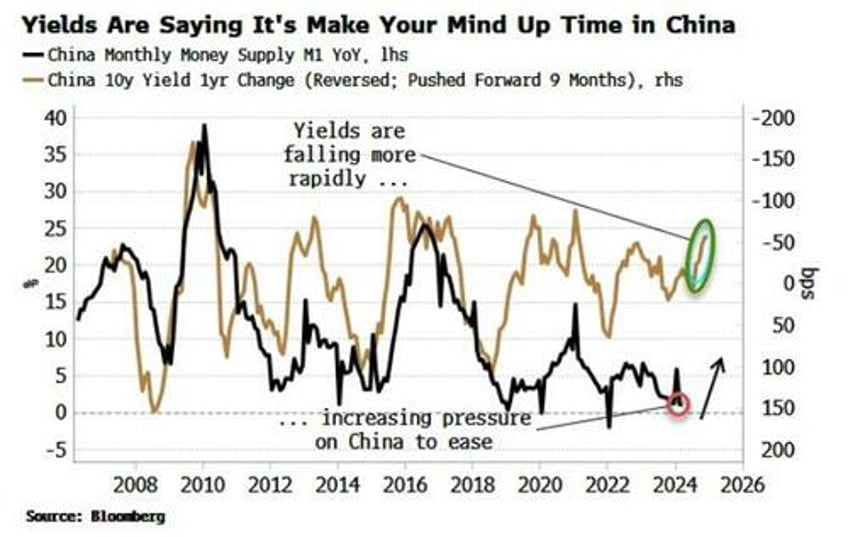

But we are entering the crunch phase, where China needs to respond forcefully, or face the prospect of a protracted debt-deflation. The signal is coming from falling government yields. They have been steadily falling all year, at a faster pace than any other major EM or DM country. Indeed yields have been rising in almost every other country.

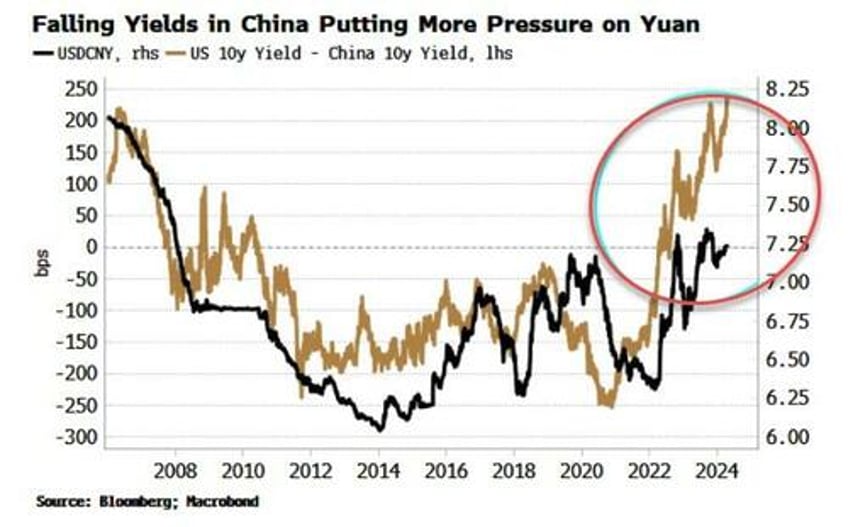

That’s a problem for the yuan. The drop in China’s yields is adding pressure on the currency. Widening real-yield differentials show that there remains a strong pull higher on the dollar-yuan pair.

The question is: will this prompt a devaluation in the yuan? The short answer is less likely than not, but it can’t be discounted, and the risks are rising as long as capital outflows continue to climb.

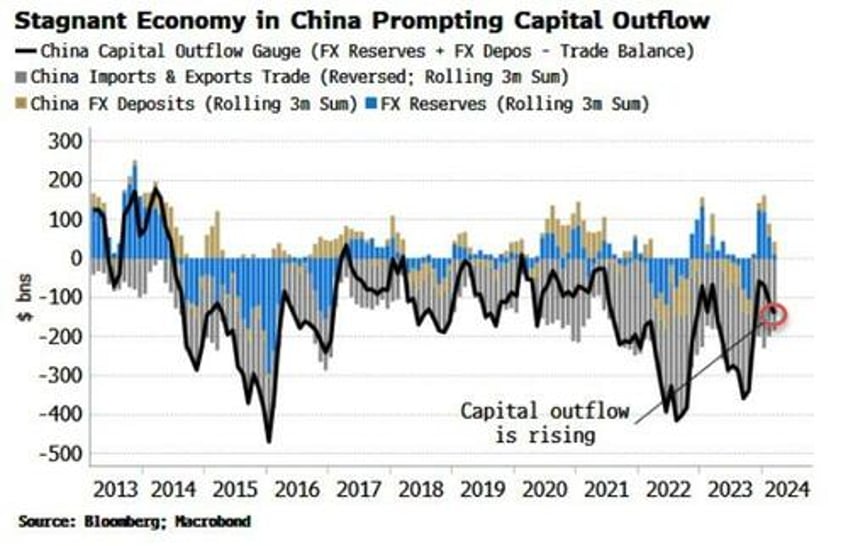

We can’t measure those directly in China as the capital account is nominally closed. But we can proxy for them by looking at the trade surplus, official reserves held at the PBOC, and foreign currency held in bank deposits. The trade surplus is a capital inflow, and whatever portion of it that does not end up either at the PBOC or in foreign-currency bank accounts we can infer is capital outflow.

This measure is rising again, as more capital typically tries to leave the country when growth is sub-par, as it is today.

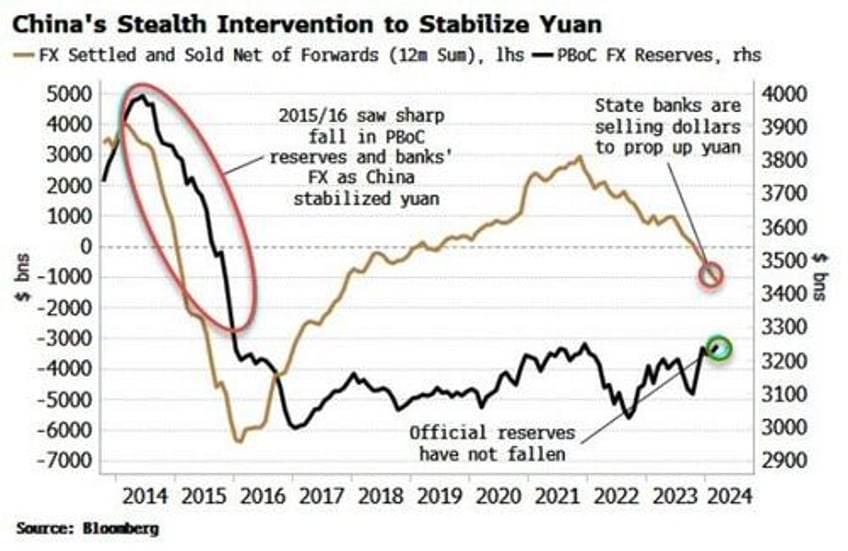

So far, China appears to be managing the decline in the yuan versus the dollar. USD/CNY has been bumping up against the 2% upper band above the official fix for the pair. But China is stabilizing the yuan’s descent through the state-banking sector. As Brad Setser noted in a recent blog, the PBOC has stated that it has more or less exited from the FX market. Instead, that intervention now takes place unofficially using dollar deposits held at state banks.

China has plenty of foreign-currency reserves to stave off continued yuan weakness (more so than is readily visible, according to Setser), but there is always the possibility policymakers decide to ameliorate the destructive impact on domestic liquidity from capital outflow by allowing a larger, one-time devaluation. There is speculation this is where China is headed, and that it is behind its recent stockpiling of gold, copper and other commodities.

However, there are risks attached to such a move, given it might be detrimental to the more normalized markets that China covets in the name of financial stability, as well potentially prompting a tariff response from the US.

A devaluation is a low, but non-zero, possibility that has risen this year. Either way, the drop in bond yields underscores that China will soon need to do something more dramatic to avert the risk of a debt deflation.

In the past, the current rate of decline in sovereign yields has led to a forthright easing response from China, with a rise in real M1 growth typically seen over the next six-to-nine months.

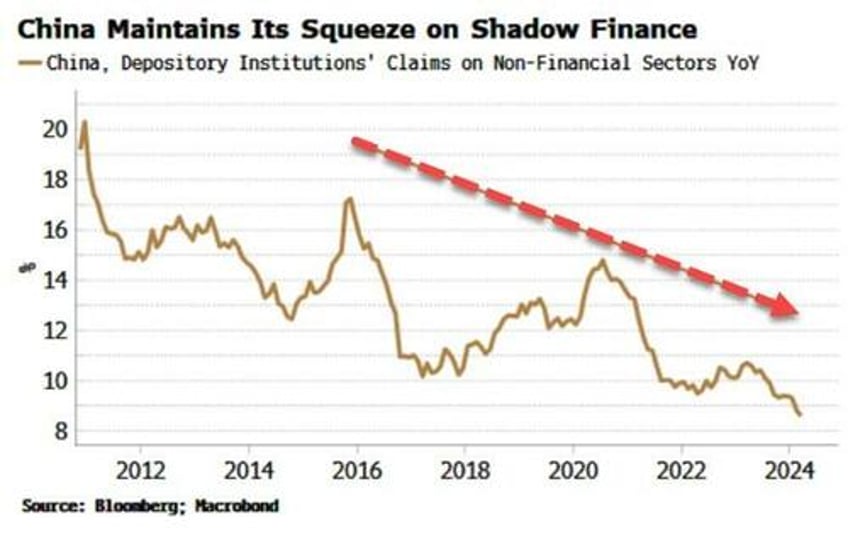

But M1 growth in China has singularly failed to bounce back so far despite several hints that it was about to. This is likely a deliberate policy choice as rises in narrow money are reflective of broad-based “flood-like” stimulus that policymakers in China have explicitly ruled out as recently as January, in comments from Premier Li Qiang. Policymakers are laser-focused on not re-inflating the shadow-finance sector, which continues to be squeezed.

Shadow finance led to unwanted speculative froth in markets, real estate and investment that China does not want to see reprised. But its curbs have been too successful. Credit remains hard-to-get where it is needed most, typically the non state-owned sectors.

The slowdown this fostered was amplified by China’s response to the pandemic. Rather than supporting household demand, policymakers in China supported the export sector, leading to a surge in outward-bound goods.

Stringent lockdowns prompted households to become exceptionally risk averse, increasing their savings, and being reluctant to spend even after restrictions were lifted, lest the government decided to paralyze the economy again at some future time.

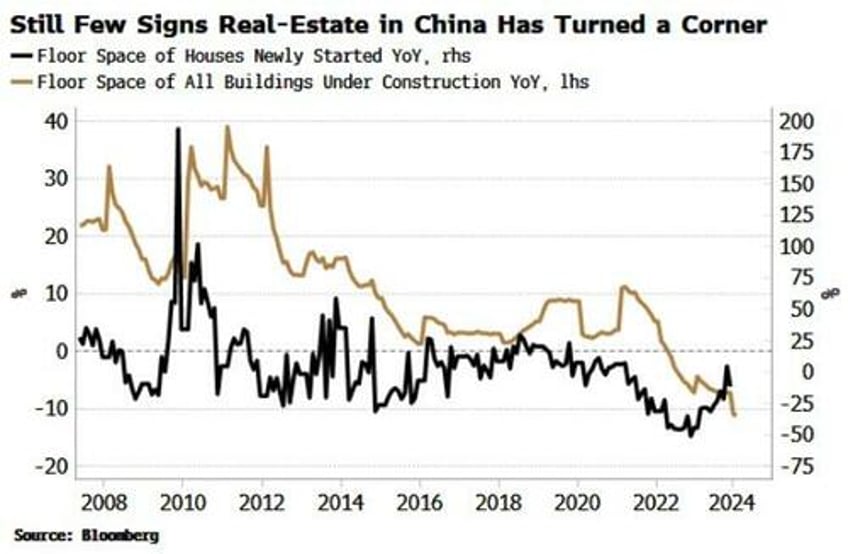

This also caused the real estate sector to implode, prompting multiple piecemeal easing measures to support housing prices and indebted property developers, to little avail so far: leading indicators for real estate such as floor-space started remain muted or weak, while the USD-denominated debt of property companies continues to trade at less than 25 cents in the dollar.

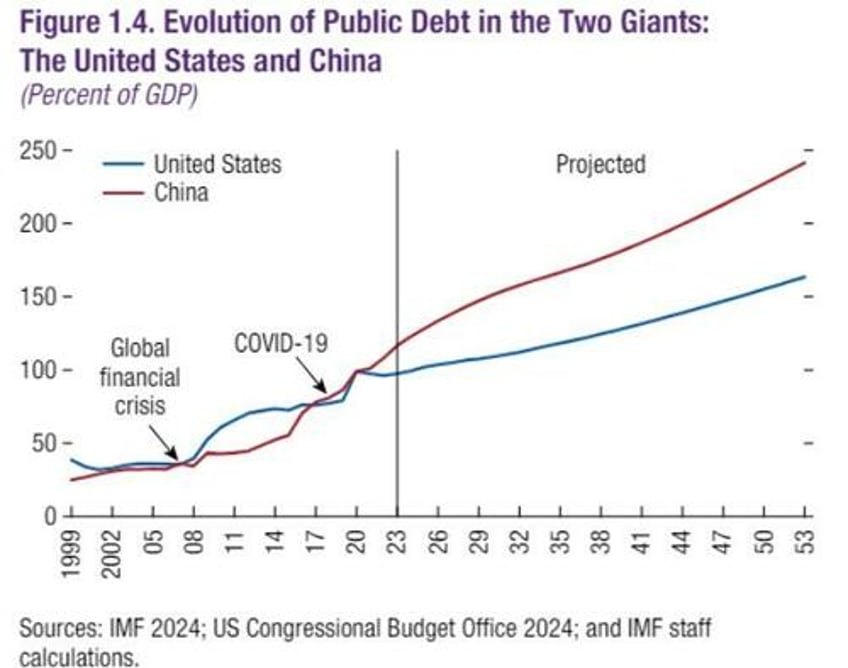

China has a large and growing debt pile that is only set to get worse as its demographics continue to deteriorate. The alarming chart below from the IMF projects public debt (including local government financing vehicles) in China to accelerate way ahead of that in the US in the coming years, to around 150% of GDP by the end of the decade. Total non-financial debt is already closing in on 300% of GDP.

Source: IMF

This raises the risk of a debt-deflation, when the value of assets and the income from them fall in relation to the value of liabilities. Debt becomes increasingly difficult to service and pay back, leading to lower consumption and investment, entrenched deflation and derisory growth that is difficult to escape.

Woody Allen once quipped that mankind is at a crossroads, one road leads to despair and utter hopelessness and the other to total extinction. China’s choices are not yet that stark, but the longer it waits to deliver an emphatic response to its predicament, they may soon become that way.