Looser financial conditions lie ahead as the Federal Reserve’s last rate hike is likely already behind us, meaning rates will become less restrictive and excess liquidity will continue to rise. Stocks are primed for one last push higher before recession risk intervenes, triggering a correction.

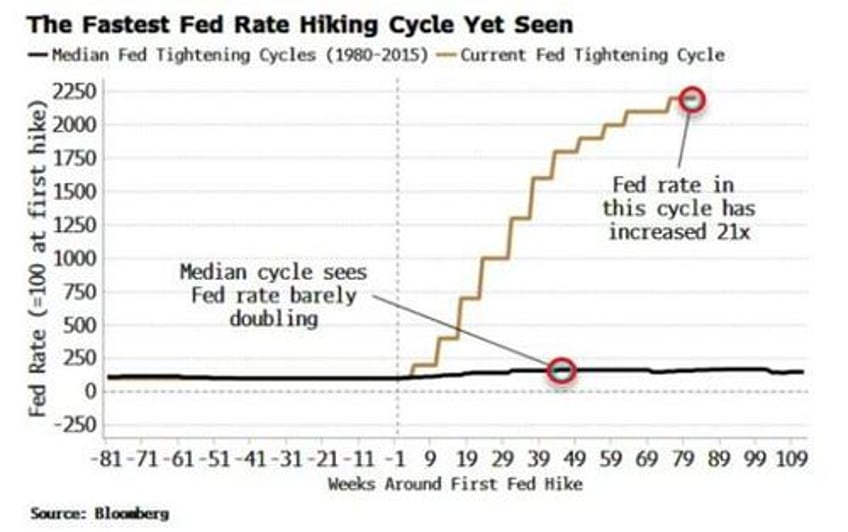

After the most rapid tightening cycle in history, the Fed is most likely done, for now at least. The end of Fed rate-hiking cycles has historically marked peak tightness in financial conditions, generating a tailwind for stocks and other risk assets.

But that’s only if a hard landing is averted - which looks unlikely.

Thus any support for stocks from relatively looser conditions is fated to be short lived.

Wednesday’s Fed meeting will be the eleventh since the bank started raising rates in this cycle. June’s meeting was a pause, while July’s hike is likely to prove to be the last - at least until inflation becomes a problem again.

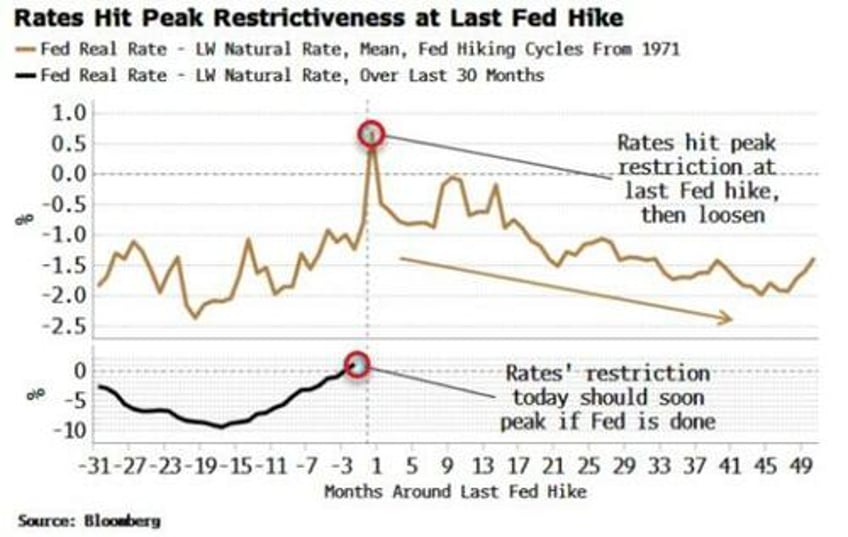

That means rates have likely hit their peak level of restrictiveness.

Using the Laubach-Williams estimate of r-star - the natural rate of interest - and comparing this to the real fed funds rate, we can see policy’s degree of restriction peaks at the Fed’s last hike.

The average move in real rates after the Fed is done is significant enough that - whether r-star has risen or fallen post the pandemic - rates are destined to become less restrictive. Even if the policy rate is held steady for some time, the totality of its impact will ease as incrementally more cuts are priced into the curve. (Forward guidance works when there is a hard floor close to where rates are desired to be, which is not the case when we are well above the zero bound).

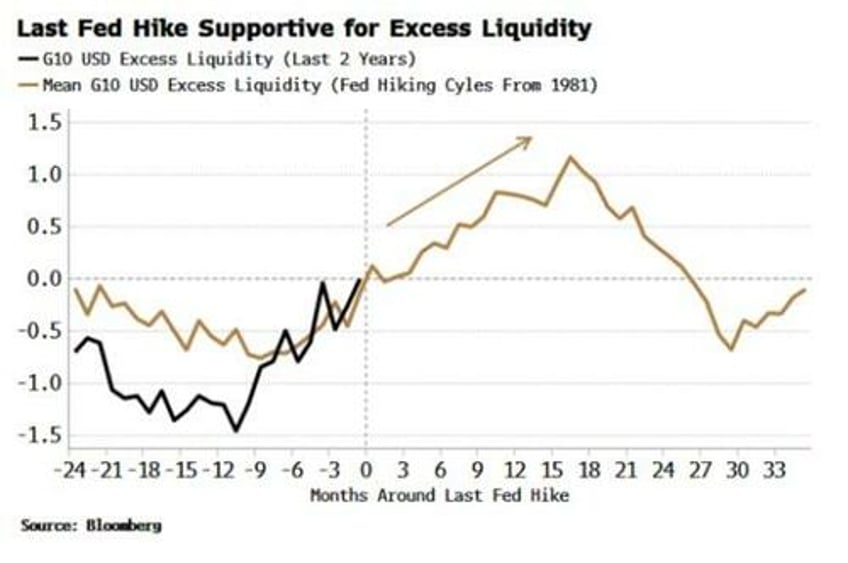

On top of this, risk assets should continue to be supported by excess liquidity, the difference between real money growth and economic growth. As the black line in the chart below shows, excess liquidity has been rising, driving the risk-asset rally we have seen over the last six months or so. There’s more to come, if history is a guide, as the brown line shows that excess liquidity typically keeps rising after the Fed’s last hike, not peaking until about a year-and-a-half later.

So far so good for risk assets. And we have prologue to support us.

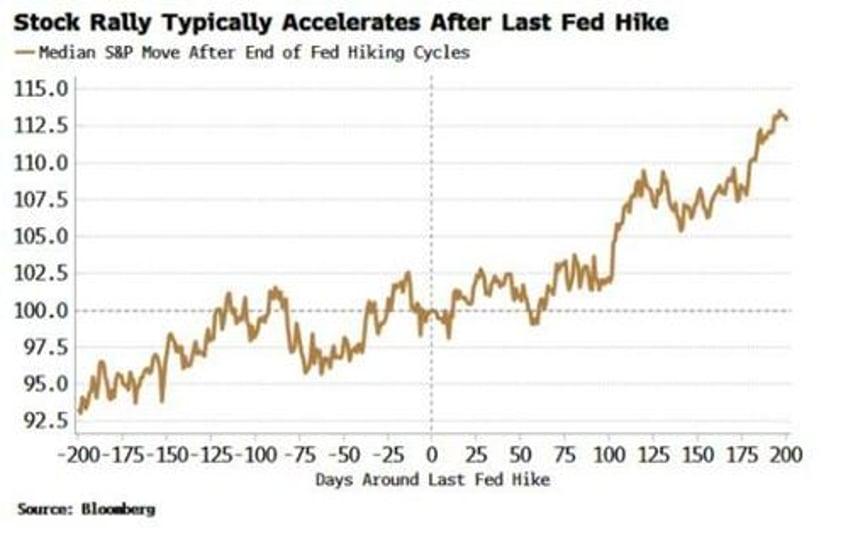

The S&P’s gradual rise toward the end of hiking cycles becomes a more rapid increase when it’s clear rates have peaked.

But a recession is the trunk-endowed beast in the room.

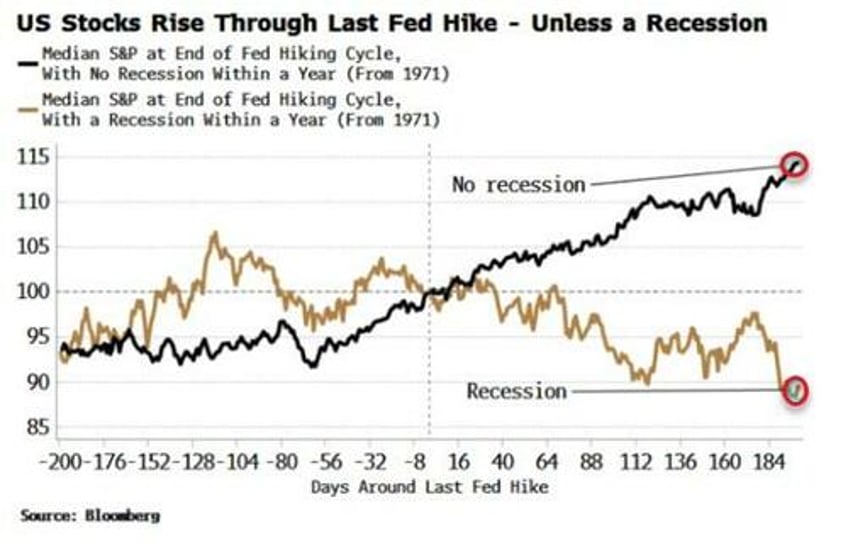

If we split up the hiking cycles that had a recession within a year of their end and those that did not, there is a clear divergence in the picture.

Recessions, and the lead up into them, overwhelm any positive effects from looser financial conditions, and coincide with a weakening in the stock market.

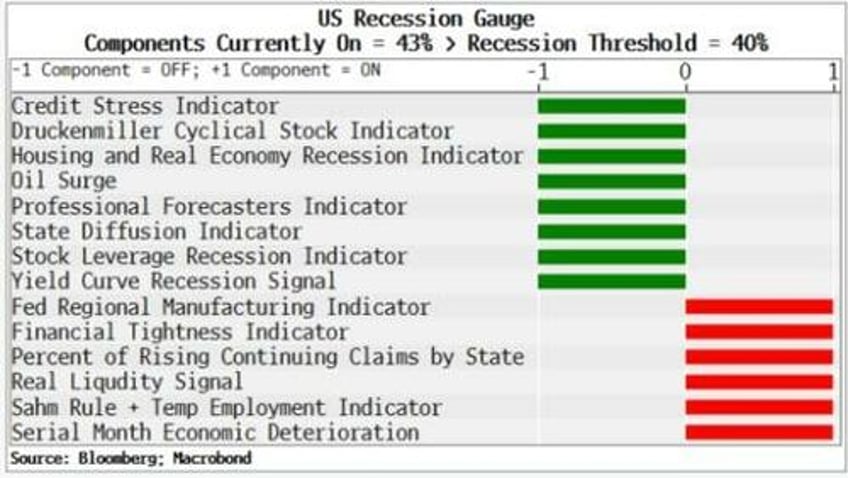

A soft or no landing has become the consensus, but recession risk remains very real. My Recession Gauge looks at a whole cross-section of economic and market-based indicators. When over 40% of them have triggered it has always preceded a near-term recession. The gauge, even though it is off its recent highs, remains above the recession threshold, intimating a downturn is close.

There is no space for complacency when it comes to recessions. They are regime shifts that happen slowly, then suddenly. Interactions between hard and soft data start to negatively reinforce one another, and past a certain point there is a cascading effect, resulting in a rapid deterioration in economic conditions. Economic data is typically revised much lower after the fact to belatedly reflect the sudden weakening.

Stocks and other risk assets, though, start to sell off well before the recession’s official NBER-defined start date, and long before the recession-dating body announces this. That’s why tracking leading indicators, such as the Recession Gauge, will be crucial in knowing when to de-risk.

From the Fed’s perspective, the risks from further hikes are becoming more balanced. Inflation has fallen to an average of a little over 3%, and by the time of the next-but-one meeting in November (assuming they hold at this week’s meeting), leading indicators show that jobs and growth data will have weakened further.

Also, the rapidity of rate hikes increases the chance their cumulative impact has yet to be fully felt. The Fed has raised rates by 525 bps in a little over a year, taking them to 5.5%, only 100 bps below the median peak of 6.5% they reach at the end of previous hiking cycles.

It’s even more dramatic when you consider rates were virtually at 0% when the Fed started raising them. In geometric terms, rates have risen faster than they ever have before. The Fed has enough justification to take its foot off the brake altogether.

We won’t know when the last Fed hike is ex ante. But there are enough reasons to lean heavily in the direction that it’s been and gone.

If so, past behavior is consistent with stocks continuing to rally as conditions loosen, until the gravity of recession takes them lower. Après la Fed, le déluge – just not immediately.