By Grace Sharkey of Freightwaves

Freight fraud has become an all-too-familiar term in the transportation and logistics sectors in recent years. Although fraud has long been a challenge in the field, industry experts observe that these criminals have evolved alongside FreightTech, leaving supply chain participants uncertain about who will bear the burden of finding solutions.

Recently, FreightWaves has received numerous reports of sophisticated freight fraud schemes.

There is the classic double-brokering scheme, in which a carrier who accepted a load from a broker re-brokers it to another carrier without the original broker’s consent, leading to payment disputes, delays and liability issues.

Double brokering can also help fraudulent carriers or brokers steal loads of freight, leaving shippers and logistics providers high and dry when insurance claims are denied.

Retailers are plagued by organized crime rings throughout their supply chains as well.

In the 2023 National Retail Federation Retail Theft study, the group found that retail shrink, or loss of inventory, totaled over $112 billion in 2022, with theft making up two-thirds of that. Seventy-eight percent of retailers in the survey also noted that solving organized retail crime was more of a priority for them than it was a year earlier.

To pull off organized freight crimes, fraudsters have become more adept at identity theft, stealing business information by using phishing emails and taking over load board accounts or even creating new ones to plot and manage these criminal acts.

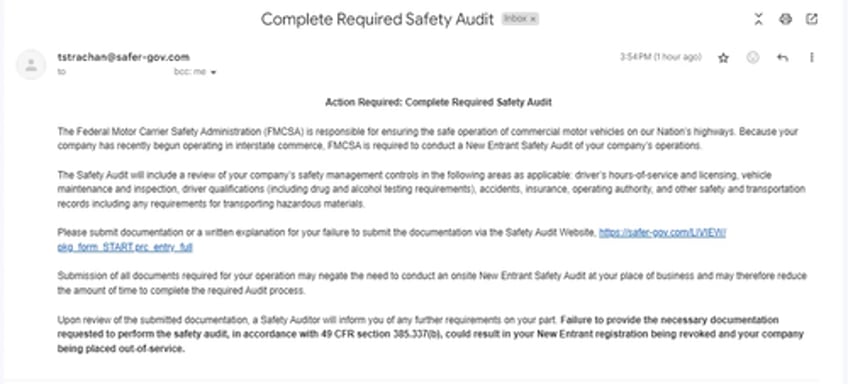

Most recently, FreightWaves has received reports from multiple carriers showcasing ways scammers are attempting to steal Department of Transportation PINs. This has surfaced in new carrier onboarding tools of fraudulent brokers and a fake New Entrant Safety Audit email purportedly from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration.

“These scams are designed for you to click the link in the email and provide personal information in which the scammer steals info like the DOT PIN and is able to change company information on file with the FMCSA,” said Adam Wingfield, founder of Innovative Logistics Group.

Fraud is not new, but it has evolved

While freight fraud has gained a high level of attention in the media and elsewhere recently, it is not even close to being a new industry phenomenon.

A seasoned freight professional, who asked to remain anonymous for business reasons, told FreightWaves he has been dealing with many of today’s common freight schemes for decades.

The professional entered the industry in the mid-1980s and has held various leadership roles, including as a dispatch manager, operations manager and brokerage manager working at container terminals, tanker divisions, and refrigerated and dry van operations.

He explained that even in the ’80s, double brokering was a major problem even for the load board operations that were posted at individual truck stops.

Christopher McLoughlin, director of compliance at Uber Freight, explained a similar concept.

“We have seen double brokering in different ways,” said McLoughlin, who has decades of risk and operations experience at C.H. Robinson and American Backhaulers. “Sometimes they were doing it to just keep the funds that the broker would pay them and not pay the carrier that actually delivered the load. Sometimes they would double broker just to augment their capacity to fulfill a commitment they can’t live up to. Now we are seeing that same schematic, but not only are they stealing the money on the load but they are now stealing the load itself.”

The anonymous professional and McLoughlin agreed that the current digital environment has created a lack of transparency, enabling fraudulent behavior.

“There is no transparency on who you are engaging with, and there are also high-volume transactions happening and people want to do everything super fast and super quick with no general awareness of who you are engaging with,” McLoughlin explained.

Added the anonymous freight professional, “We have evolved to the point where they can commit fraud easily online, create a fake insurance company, fake certificates that pass off as real, and now the poor legit broker is liable for the lost cargo and the double freight payment.”

Can it be solved?

Over the past few years, a number of identity and validation technologies have come out, receiving large investments for their promise of helping to mitigate these crimes. Companies like Highway, Carrier Assure, Verified Carrier and FreightValidate offer different strategies to help shippers and brokers make educated decisions and bring the transparency that McLoughlin and the freight veteran both mention.

Most individuals FreightWaves spoke to have found that while these technologies can help, they are not solving the problem.

Don Everhart, chief technology officer at FreightVana and a past tech leader at Knight-Swift Transportation, explained that his current company has adopted an approach of using everything at his disposal to de-risk against fraud and other cybersecurity issues.

“Adoption of a zero-trust framework has helped bridge that gap as we work to verify identity authorization on every interaction,” Everhart told FreightWaves. “We use several platforms in the space that have their specific strengths and weaknesses. In my personal network, I can’t think of a single company only utilizing one fraud prevention or vetting platform.”

Is the government helping?

While the technology is working toward providing the industry relief, leaders have been looking to regulators for answers.

The FMCSA, an agency of the U.S. Department of Transportation, oversees double-brokering schemes. Through the 2012 Motor Carrier Protection Act, also known as MAP-21, it gained the authority to assess civil penalties of up to $10,000 per incident.

But a court decision in 2019 has made the situation more complicated.

Known as the Riojas decision, a case centered around violations by a motor carrier company raised questions about appropriate enforcement and prosecution authority. The FMCSA typically handled regulatory compliance and civil enforcement, but the nature of the violations in this case necessitated criminal prosecution.

The court’s interpretation emphasized that the FMCSA, while capable of imposing civil penalties, did not have the legal infrastructure to handle criminal cases. The DOJ, with its legal expertise and resources, was deemed the appropriate authority for such matters.

“Without statutory authority to assess civil penalties administratively for violations of FMCSA’s commercial regulations, the FMCSA’s ability to effectively enforce these regulations is significantly limited,” said the agency in its recent “Unlawful Brokerage Activities Report.” “Unless a regulated entity that violates FMCSA’s commercial regulations voluntarily resolves its noncompliance, FMCSA must refer cases to the [Department of Justice] for enforcement of those regulations. The need to refer cases to the DOJ complicates and hampers the ability of FMCSA to enforce the Agency’s commercial regulations, including those regarding unauthorized brokerage.”

The FMCSA did note that even with its limited authority, it reviewed 35 household goods brokers in four states in 2023, finding 166 violations, closed over 540 complaints and issued 17 letters of probable violations.

Until its ability to assess civil penalties was curtailed, it did issue 20 notices and penalties between 2014 to 2019.

FreightWaves reached out to both the FMCSA and the DOJ to learn more about how these notices are shared with the public and how both entities plan to increase public outreach on fraud-related issues. Neither responded prior to publication.

The comment in FMCSA’s report that confused most leaders FreightWaves spoke to, though, was this:

“FMCSA is still assessing the relationship between motor carrier safety and incidence of unlawful brokerage. While the Agency has received multiple expressions of concern from stakeholders regarding fraud related to ‘double brokering,’ it lacks data to quantify or confirm a safety impact.”

“I disagree completely with the statement,” said Everhart. “The industry is happy to provide data; the challenge to the agency is what recourse do they have?”

Said McLoughlin: “We’ve been working with the [Transportation Intermediaries Association], and when we have double-brokering incidents, we are reporting them through the clearinghouse. … We’re willing to work with [FMSCA] if there’s specific data points that they need to know that we’re not providing. We’d love to have feedback. The TIA has fed tens of thousands of these reports into that clearinghouse, and we have yet to see action on a single one. So if we’re continuing to put these reports in and we’re not providing the right information, I’d love to have that conversation of what information is necessary to gain that transparency.”

The Owner-Operator Independent Drivers Association told FreightWaves it found the response comical, stating FMCSA plays a role in creating the problem.

“It’s infuriating but also kind of the way it is. When the industry was deregulated, they opened the doors to everyone – good and not so good,” said Todd Spencer, president of OOIDA. “The ball is missed by not doing more upfront scrutiny of those you grant authority to do business.”

Is it the perfect crime?

With a lack of technology to find these bad actors and policing agencies pointing the finger at each other’s jurisdictions, has freight fraud become the perfect crime?

FreightWaves discussed the evolution of freight crimes with another technology leader and expert in the industry who wished to stay anonymous for fear of retaliation.

“Unfortunately, in many cases it is viewed as a victimless crime because it is B2B, jurisdiction is rarely clear, and no specific entity is handling all the caseload,” the source explained. “Depending on the fraud vector and specific crime, it may be handled by local law enforcement, a sheriff’s department or the FBI. Another challenge is that many times it gets grouped with cybercrime because of the nature of the attacks, which has an overwhelming case volume and limited resources.”

Even McLoughlin shared that Uber Freight has a little over 50 people who focus on deterring these crimes. While FreightWaves was not able to verify the number of representatives at the FMCSA or the DOJ working to fight freight crime, McLoughlin and co-worker Bill McDermott, a freight investigator for Uber Freight with 20 years of experience with the FBI, agreed it would take more resources than the policing authorities are currently using.

“It’d be a great opportunity for a public-private partnership. But like everything I’ve ever worked on in the federal government, it’s about whose name is going to be at the top of that letterhead. At this point in the game, it shouldn’t matter. If one group can come out and try to coordinate this and get that plan sprinkled across the different agencies, we would have a better result in the end,” he said.

Spencer also noted that OOIDA is doing its best to push House Bill HR 8505, which would expand the authority of the FMCSA to assess penalties again.

“These are important issues that won’t be solved without government intervention. Our challenge here at OOIDA is to find the ways to inform and motivate truckers to be politically engaged on these issues. Make the phone calls, send the emails, be persistent,” said Spencer.

Addressing these problems today

If local law enforcement, federal agencies and FreightTech entrepreneurs are of limited help, how do stakeholders prevent freight fraud today?

Everyone FreightWaves spoke to came to the same conclusion: collaboration and transparency at all costs.

McDermott explained that this might mean fessing up when something goes wrong.

“People get embarrassed and don’t want to say, ‘Hey, I’m a victim,’” he said. “Here we take our victories but we take our lumps as well and we try to learn from each scenario. I fall back on the training, experience and connections I made within the bureau and other federal agencies to say, ‘This is what we saw. This was their source and their methods, and this is how they perpetrated the scam. Where have you seen this before?’ From there we can narrow our focus and establish our own internal trip wires.”

The anonymous industry professional explained he would love to see load board providers take a better approach toward verifying users and more quickly removing those who draw complaints. He also said taking an extra step to educate shippers could help prevent a lot of fraud.

“Your shippers need to help verify the carrier that is supposed to be there for pickup. A lot of shippers are also in a hurry to turn loads out. You have to build a relationship with the shipper and explain to them the importance of verifying that it is the correct carrier and the documents and certificates that you shared with them match what the driver has on hand. You want to have another layer of verification in person,” he said.

Nonetheless, the technology expert believes until the crime becomes unappealing to fraudsters, not much will change.

“The way to prevent freight fraud is simple. As an industry, we must make it less economically attractive to the bad actors. As long as the reward outweighs the risk, it will remain attractive,” he said.