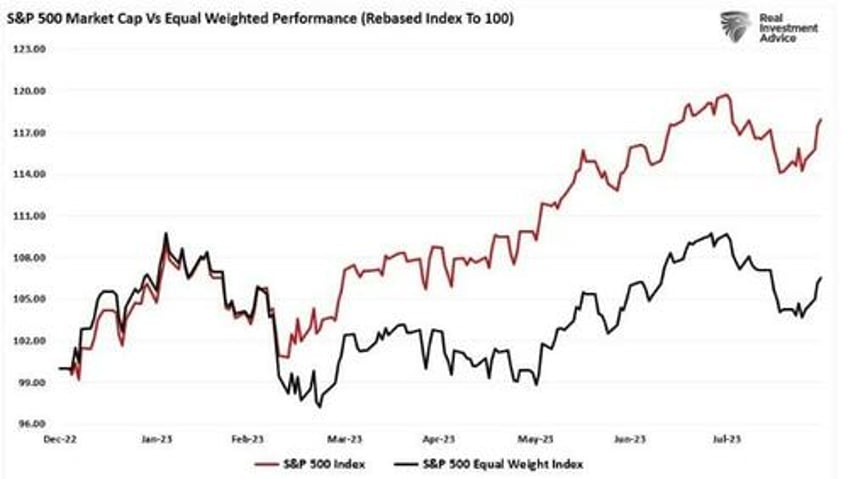

Mega-cap stocks continue to dominate the market in 2023. The question is, why? After all, many other great companies have arguably much better valuations and fundamentals. Yet, those companies continue to lag the market’s overall returns as the bifurcation between the Mega-cap companies and everything else widens. The chat below clarifies the problem, which compares the market-capitalization weighted index to the equal-weight.

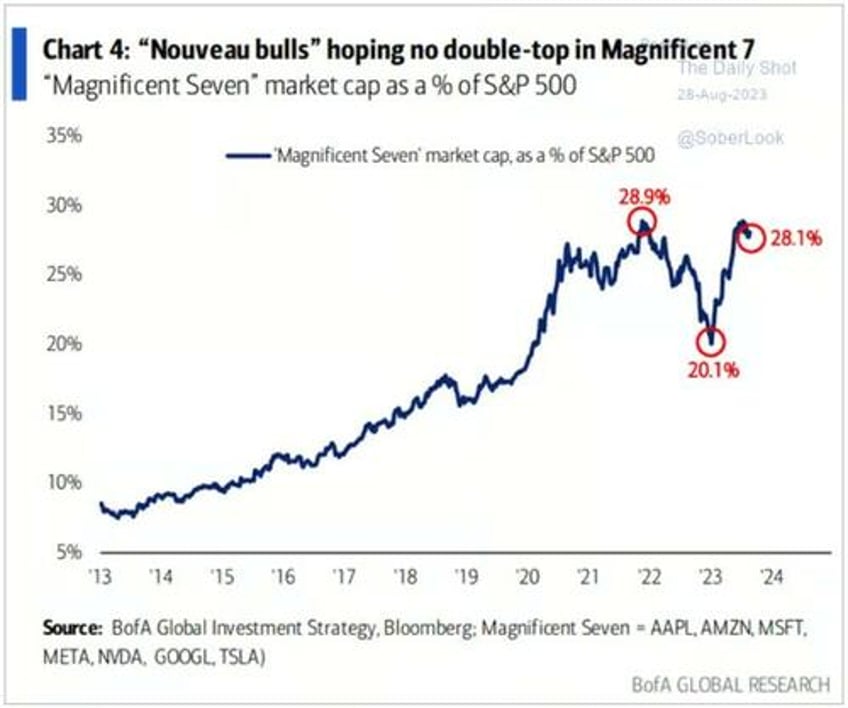

The bifurcation between the top 10 companies, as measured by market capitalization, and the other 490 stocks in the index has created an illusion of market bullishness. As we discussed just recently in “Investing In 2024:”

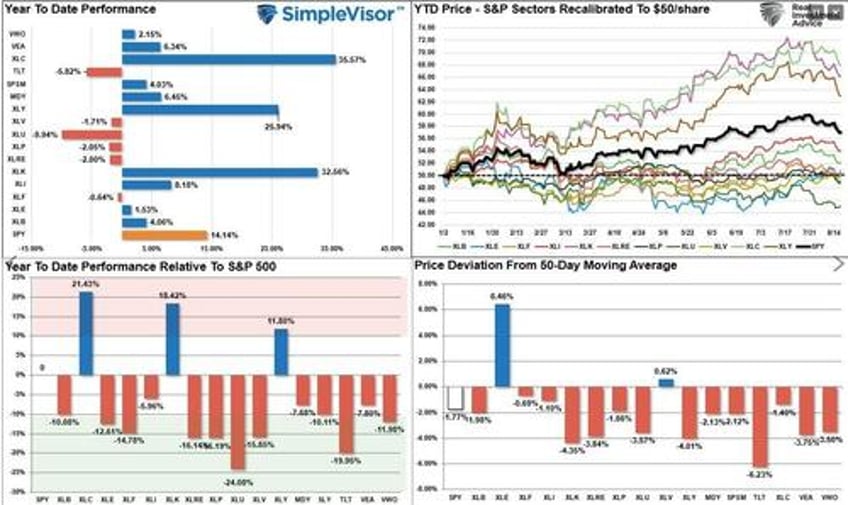

“The surge in the most hated sectors last year has been the main driver of this year’s broad market performance. If we strip out the performance of those three sectors, the market would be near flat on a year-to-date basis.”

Despite the extremely crowded trade into the three sectors comprised of those ten stocks, we continue to see professional investors crowd into those shares at a record clip.

The question is, why are professional managers seemingly chasing these stocks with reckless abandon?

The answer is more simplistic than you may think.

Career Risk And The Passive Effect

For investment managers, generating performance is necessary to limit “career risk.” If a manager underperforms their relative benchmark index for very long, they most likely won’t have a “career” in the investment management business. Currently, there are two drivers for the mega-capitalization stock chase. First, these stocks are highly liquid, and managers can quickly move money into and out without significant price movements.

The second is the passive indexing effect.

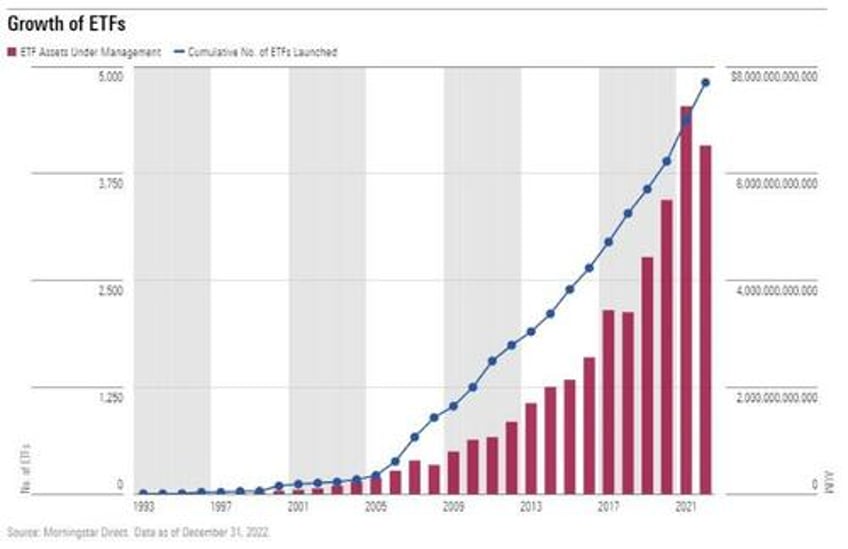

As investors change their investing habits from buying individual stocks to the ease of buying a broad index, the inflows of capital unequally shift into the largest capitalization stocks in the index. Over the last decade, the inflows into exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have exploded.

That ETF issuance surge and the assets’ growth under management fuel the performance of the top 10 stocks. As we discussed previously:

“In other words, out of roughly 1750 ETF’s, the top-10 stocks in the index comprise approximately 25% of all issued ETFs. Such makes sense, given that for an ETF issuer to “sell” you a product, they need good performance. Moreover, in a late-stage market cycle driven by momentum, it is not uncommon to find the same “best performing” stocks proliferating many ETFs.”

Therefore, as investors buy shares of a passive ETF, the shares of all the underlying companies must be purchased. Given the massive inflows into ETFs over the last year and subsequent inflows into the top-10 stocks, the mirage of market stability is not surprising.

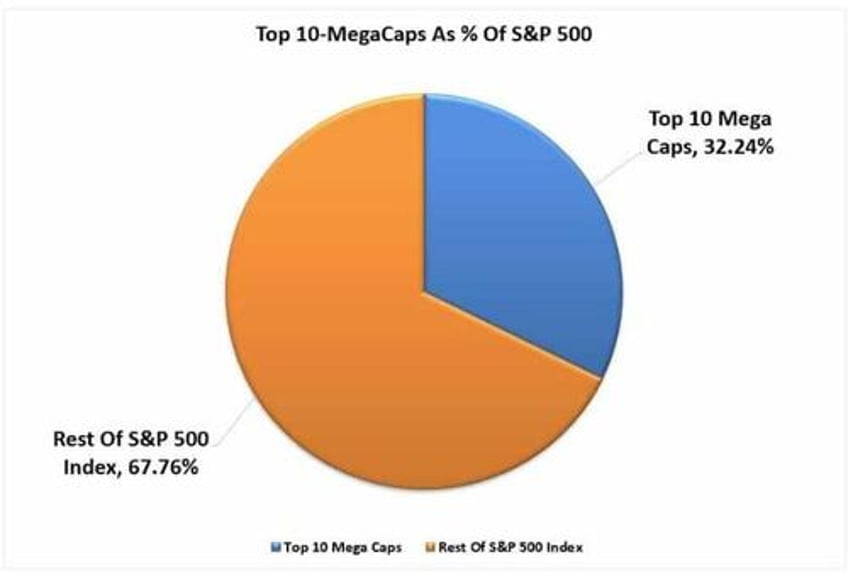

As shown, for each $1 invested in the S&P 500 index, $0.32 flows directly into the top 10 stocks. The remaining $0.68 is divided between the remaining 490 stocks. This “passive indexing effect” has changed the market dynamics over the last decade.

However, the “passive effect” is only one reason portfolio managers hide in these massive companies.

The other reason is “safety.”

Safety In Liquidity

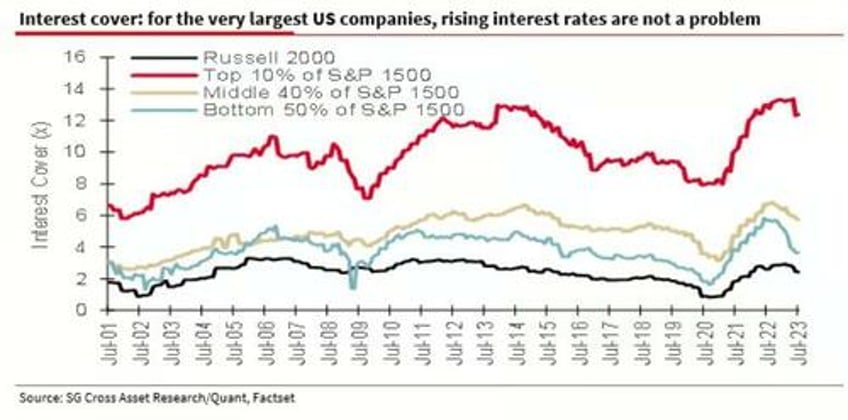

If and when the economy slips into a recession, earnings and revenue will decline for companies. Given the current level of interest rates, inflation, and reversal of monetary liquidity post-pandemic, the risk of recession is higher than normal. Higher interest rates, in particular, currently pose the largest threat to small and medium-sized companies. As Andrew Lapthorne of Societe General recently noted:

“The largest 10% of companies represent 62% of the overall non-financial market cap of the S&P 1500, so from a market perspective, it would appear that interest rates are not yet affecting the balance-sheet stress of the market overall. But lower down the size scale, things are tough and getting tougher. Interest coverage at the bottom 50% of S&P 1500 companies and the smallest quoted companies (as listed in the Russell 2000 index) falling sharply from low levels.”

These smaller companies do not have access to the capital markets as easily as larger capitalization companies and do not have the massive cash balances the mega-cap companies hold.

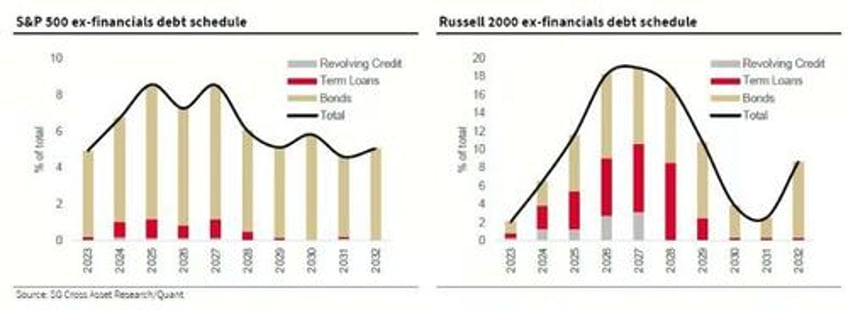

“It stands to reason that smaller quoted companies in the Russell 2000 index, as well as unquoted companies, don’t have as much access to corporate bond issuance so have been unable to lock into the near-zero long-dated fixed borrowings that the larger companies have.”

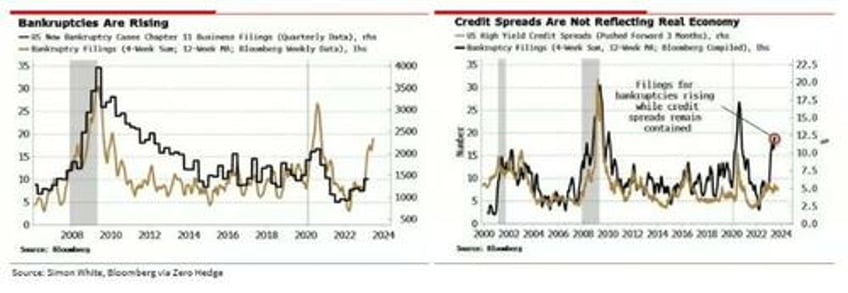

As that debt wall of term loans hits over the next few years, higher borrowing costs are going to raise the risk of defaults and bankruptcies. While we may not be in a recession yet, doesn’t mean it can’t happen. As noted by Simon White via Bloomberg, tightening financial conditions have seen corporate bankruptcies rise by 71% since last year. If financial conditions are still elevated over the next few years, that bankruptcy risk increases markedly.

As Albert concludes:

“Contrary to what the mega-cap valuations might suggest, smaller companies remain the beating heart of the US economy – maybe the mega-caps are more like vampires sucking the lifeblood out of other companies. It seems the lights are going out all over the US smaller-cap corporate sector.

They weren’t able to lock into long-term loans at almost zero interest rates and pile it high in the money markets at variable rates. Ultimately the pain for US small- and mid-cap companies will trigger the recession most economists are now giving up on, and hey, guess what? I think we’ll soon find out that even the large- and mega-cap stocks might not be immune to the indirect recessionary impact of higher interest rates after all.“

Portfolio managers must chase the market higher or potentially suffer career risk. Therefore, the easiest place to allocate cash is the mega-capitalization companies with low risk of bankruptcy or default and extremely high liquidity.

I agree with Albert that current exuberance in the markets and the belief of a “no landing” scenario are likely largely overblown. Substantially tighter financial conditions remain the biggest risk to the markets. Therefore, when the Fed begins cutting rates to fix what it broke, we will see the rotation to safety occurring simultaneously.

Mega-Cap Will Dominate Until It Doesn’t

For now, there is little to deter portfolio managers from chasing the mega-cap stocks for performance reporting purposes. As noted, a big divergence between the manager’s performance and the benchmark index will lead to “career risk.” However, the problem is compounded by retail investors piling money into passive ETFs.

There is a basic belief by investors that “for every buyer, there is a seller.”

However, the correct statement is:

“For every buyer, there is a seller….at a specific price.”

In other words, when the selling begins, those wanting to “sell” overrun those willing to “buy.” Therefore, prices drop until a “buyer” is willing to step in.

That surge in selling pressure creates a “liquidity vacuum” between the current price and a “buyer” willing to execute. In other words, just as professional managers are trying to sell their shares of Apple (AAPL), the other 343 ETFs that own Apple are vying for the same scarce pool of buyers in a declining market.

Furthermore, advisors are also actively migrating portfolio management to passive ETFs for some, if not all, of the asset allocation equation. The rise of index funds has turned everyone into “asset class pickers” instead of stock pickers. However, just because individuals are choosing to “buy baskets” of stocks rather than individual securities, it is not a “passive” choice but rather “active management” in a different form.

With the concentration of risk in a handful of stocks, the markets are set for a rather vicious cycle. The concentration of holdings and the subsequent lack of liquidity suggest reversals will not be a slow and methodical process. Rather, it will be a stampede with little regard for price, valuation, or fundamental measures as the exit narrows.

I suspect that March 2020 was just a “sampling” of what will happen when the next “real” bear market begins.