By Seth Carpenter, Morgan Stanley chief global economist

January’s FOMC meeting, labor market data, and inflation data have all pushed the market from pricing nearly 200bp of Fed rate cuts starting in March to broadly aligning with our view of cuts starting in June and cumulating to 100bp at the end of the year. But between now and year-end comes the election…a fact that has driven client questions about the implications for Fed independence.

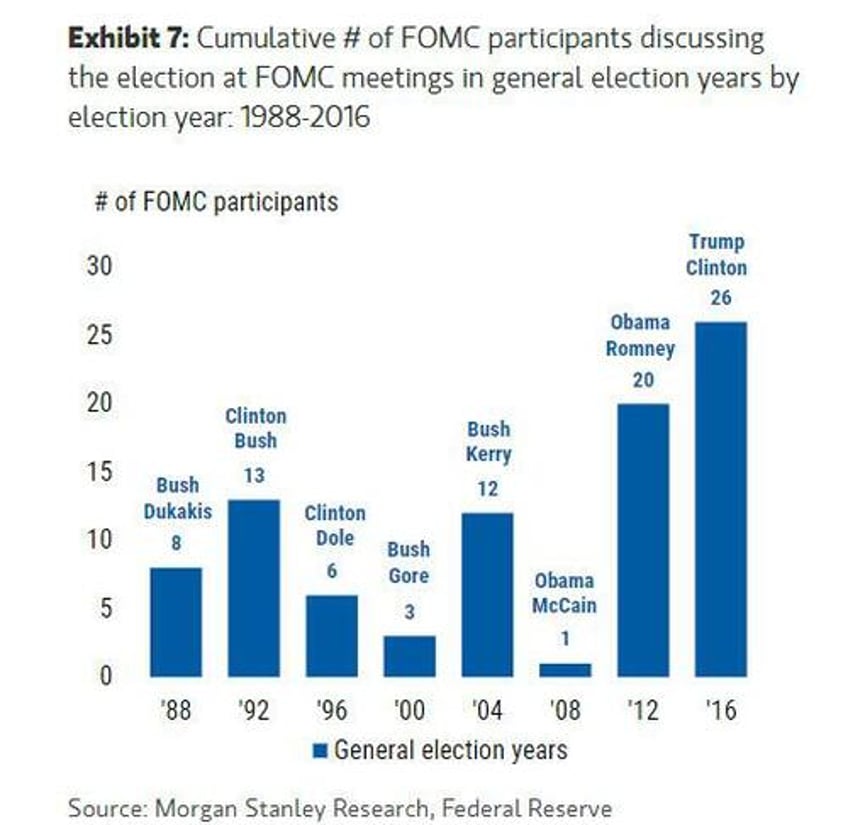

Matt Hornbach and I wrote a piece last month emphatically making the case that the election will not affect Fed policy this year. Client questions range from “Does the Fed have to cut more because it is an election year?” to “Does it have to start cutting in June because otherwise it will be too close to the election?” and sometimes “Won’t the Fed seem too political if it cuts at all?” From my first-hand experience in 15 years of working at the Fed, I can confidently say that the institution does not change based on the electoral cycle. In the piece with Matt, we show that there is no discernible difference in Fed decisions between years with elections and those without. But don’t take our word for it. Matt dug through years of FOMC transcripts, and the Committee’s discussions of elections only reflect macroeconomic concerns. Will uncertainty before the election damp spending? Will a change in fiscal policy drive aggregate demand? Whatever questions may arise, the evidence is clear that the Fed’s election-year decisions will be driven by its mandate, not by attempts to influence the outcome of the election.

But as the saying goes, “Elections have consequences,” and what happens after the election is a different story. Specifically, former President Trump has stated that if he is re-elected, he will not re-appoint Chair Powell. In collaboration with our public policy research colleagues, we tackled the question of how much risk such a circumstance would pose to Fed independence. The first point to make is that any such change would come a year after the new president is inaugurated, so it’s an issue for 2026, not 2025. While a new chair could easily bring changes to communication and perhaps more dissents at Fed meetings, the worst-case scenario that many clients worry about will likely be avoided.

Although the president nominates the chair and the members of the Federal Reserve Board, the next president’s term will have only two vacancies, far short of a majority. Also, the Senate must confirm the president’s nominees, adding another layer of checks and balances against a subservient Fed. And the Fed Board isn’t the whole story. The FOMC comprises the Fed Board plus the 12 Reserve Bank presidents, and the Reserve Bank presidents are chosen through a wholly separate process, specifically designed to insulate the FOMC from political pressure.

Another safeguard of independence is that according to the letter of the law, the FOMC picks its own chair, and only convention makes that person the chair of the Fed Board. In practice, of course, I suspect the FOMC would defer to the choice of the president and the Senate, but that safeguard exists, nevertheless. History also shows that Paul Volcker faced tremendous dissent in his fight against inflation, he lost one Board vote, and news reports stated that he threatened to resign when faced with opposition within the FOMC. The institution is set up with many layers to prevent any president from getting a “rubber stamp” Fed chair.

Overall, we are highly convicted that Fed policy this year will not be swayed by the fact of the election. The place simply does not work that way. And for the first year of the next administration, whoever wins, Chair Powell’s place is secure. A new Fed chair could very well shift the FOMC’s reaction function at the margin, and each president and Senate get to express their views about the best candidate. But the institutional process is designed to guard against the extreme case of a Fed that is directed by the White House instead of the dual mandate.

More in the full note available to pro subs.