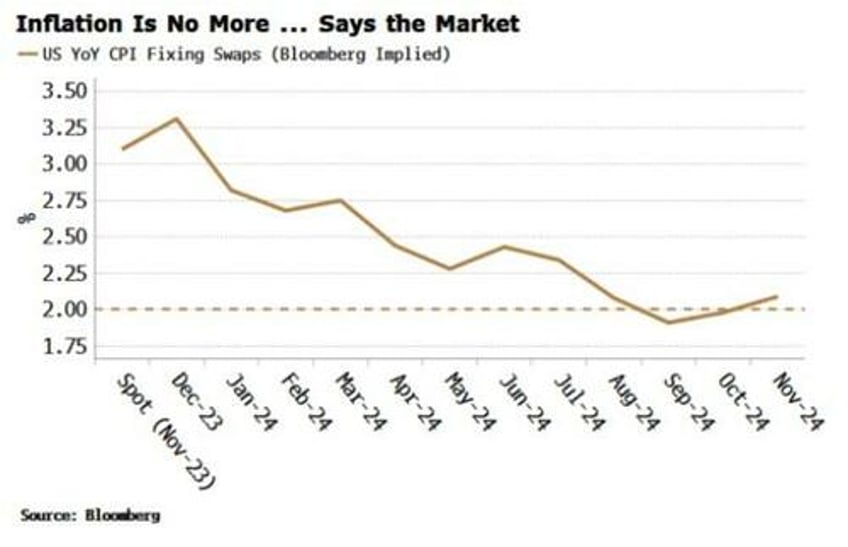

Confidence is growing that inflation has been defeated.

What is typically forgotten is that it is a very lagging indicator, with most arguments based on the recent disinflation trend continuing. But forward-looking analysis tells a different story, with price pressures proliferating on several different fronts.

Stocks, bonds, credit and the inflation market offer next to no insurance against a resurgence in price growth.

I didn’t plan to write about inflation today.

But that was until I read Joseph Stiglitz’s A Victory Lap for the Transitory Inflation Team in Project Syndicate, with which I strongly disagreed.

Inflation may be down, but it’s very much not out.

A Victory Lap’s two main points are that Team Transitory was right, and that tight monetary policy – and the concomitant risk of a large rise in unemployment – was unnecessary.

On the first point, as Chinese premier Zhou Enlai quipped when asked what was the impact of the French Revolution: “it’s too early to tell.”

And on the second, the reason why unemployment didn’t rise more is ultimately down to precisely why inflation is highly likely to remain persistent: the considerable fiscal deficit.

But first, forward-looking data show that inflation pressures are beginning to build on multiple fronts.

I’ll focus on three of the most important here:

money,

supply chains, and

China.

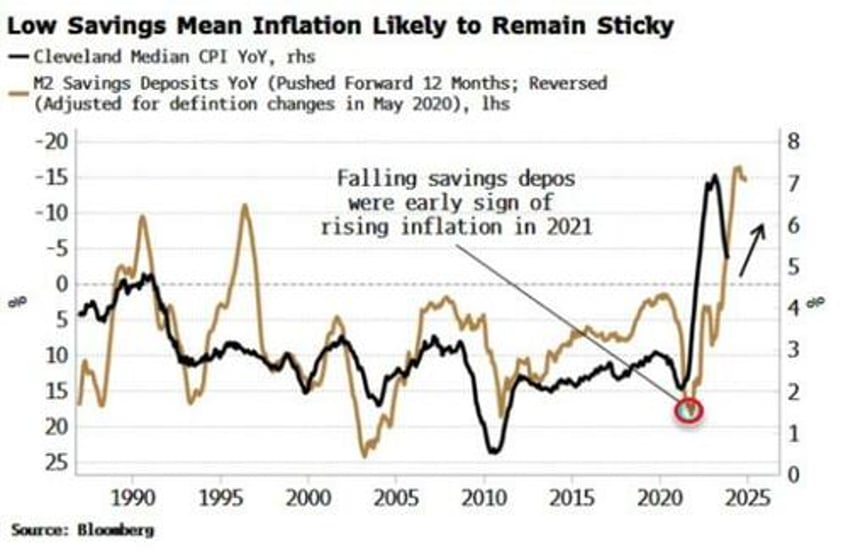

Too often how money is related to inflation is misunderstood.

A standard analysis looks at the aggregates: M2 is contracting on an annual basis, ergo that’s bad for inflation. But M2 is counter-cyclical. It consists mainly of saving deposits. When economic conditions are weak, people tend to move money out of current accounts into savings accounts, and M2 rises, and vice-versa when the economy is strong.

What leads inflation is not aggregate M2, but the inverse of the savings-deposits component. It was the fall in savings in late 2020 that gave one of the earliest signs of the coming rise in inflation.

As the chart below shows, savings-deposit growth remains low today, which points to a re-rise in inflation later this year.

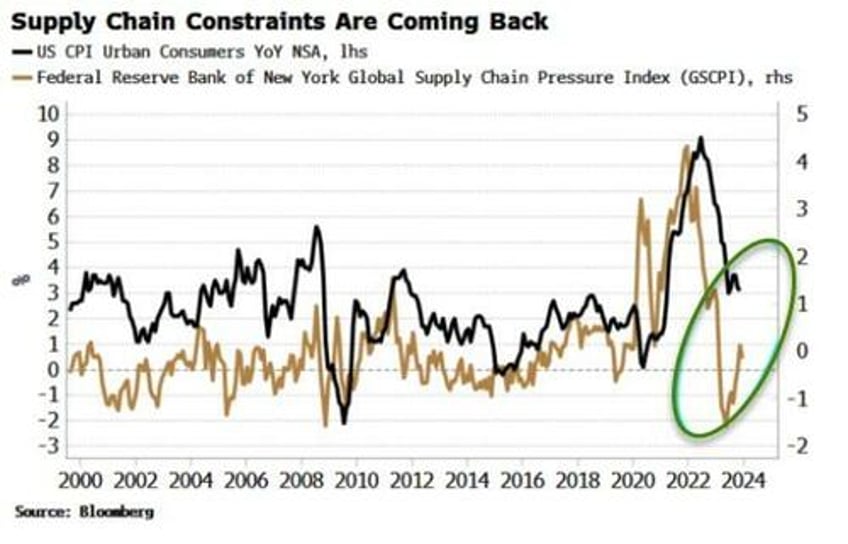

Supply chain constraints have eased considerably since the height of the pandemic, which helped drive inflation lower. But that’s in reverse now, with supply chains tightening again.

One topical example is the skirmish in the Red Sea.

But there’ll be more to come: heightened geopolitical tensions only mean supply chains will remain vulnerable to inflation-causing disruption.

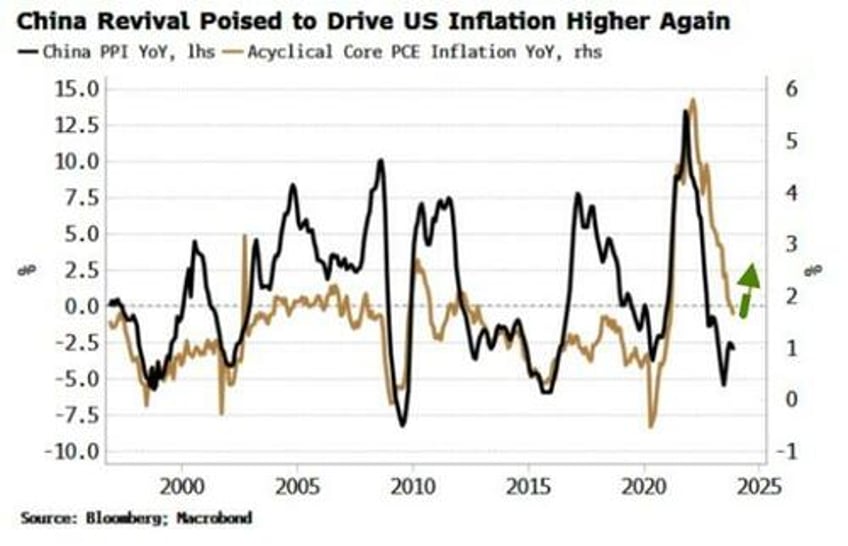

It’s China, though, that doesn’t seem to be part of the reckoning in any inflation analyses.

It was the ghost at the global inflation feast, being the only country to experience outright consumer deflation since the pandemic.

China’s influence on the last year-and-a-half’s disinflation can be seen by splitting US core PCE into cyclical and acyclical components. Cyclical consists of those components that are highly correlated to Fed policy, while acyclical is everything left over.

Cyclical inflation remains elevated, inferring the Fed has had little direct impact on the decline in US inflation.

Instead, most of the heavy lifting has been done by acyclical inflation.

And what is quite remarkable is that acyclical PCE is highly correlated to PPI in China, i.e. depressed inflation in China has likely been a key influence on US disinflation.

This means when China recovers, inflation in the US is likely to be bolstered by the type of price growth the Fed has little control over, even as the lagged effects of its tight monetary policy continue to bite.

Some are of the view that China is nearing its Minsky moment, but I don’t think we’re there yet. Instead the impact of targeted easing in property markets and continued monetary easing will cumulatively build, and eventually kickstart at least a transient recovery.

Floor space started on houses is now rising sharply, and the debt of real estate companies is climbing off its lows, while net injections of liquidity by the PBOC are near levels last seen when China was in the midst of its so-called flood-like stimulus.

More pertinently, leading indicators of inflation in China are rising.

Shanghai freight container rates have been increasing (supply-chain pressures again), which points to higher PPI — with US inflation likely not long behind.

On a forward-looking basis it’s thus hard to agree with the market’s benign inflation expectations. Or put another way, if inflation was going where the market anticipates, then you wouldn’t want to see the data in the above charts.

Why has inflation fallen while unemployment has barely risen? In answering this we get to the central point of why price growth is likely to be persistent. Normally over 500 bps of Fed rate hikes would have done much more economic damage. That they haven’t is principally due to the government running the largest peacetime, non-recessionary deficit yet seen.

The reaction function of governments, not just in the US, has changed in recent years. With electorates’ rising expectations of what their governments should shield them from — job loss, ill health, high energy prices, even death — it is becoming increasingly difficult to see how sovereigns can rein deficits back in to pre-pandemic norms any time soon.

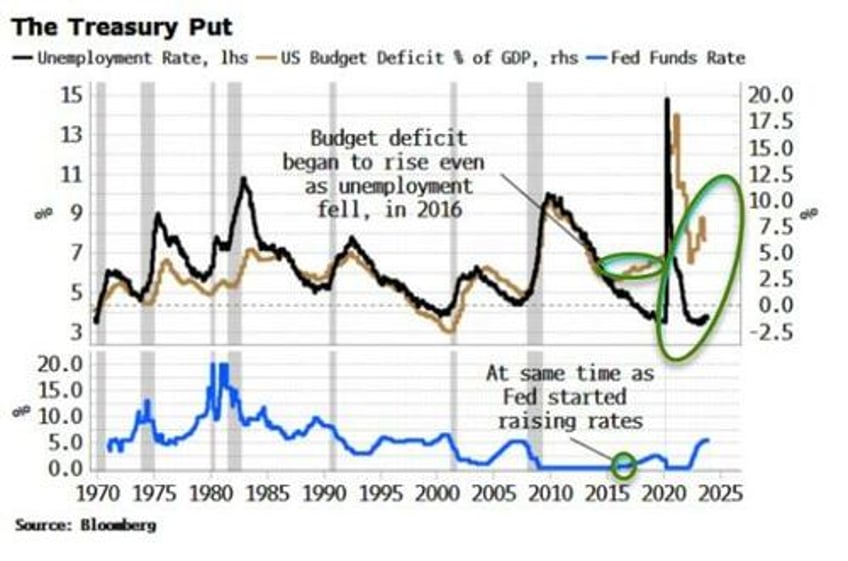

This Treasury put emerged in the mid 2010s. Before then, the US fiscal deficit used to move in line with the unemployment rate. But around 2015, when the Fed started raising rates for the first time since the GFC, the fiscal deficit rose even as unemployment continued to fall. Spending had become overtly pro-cyclical.

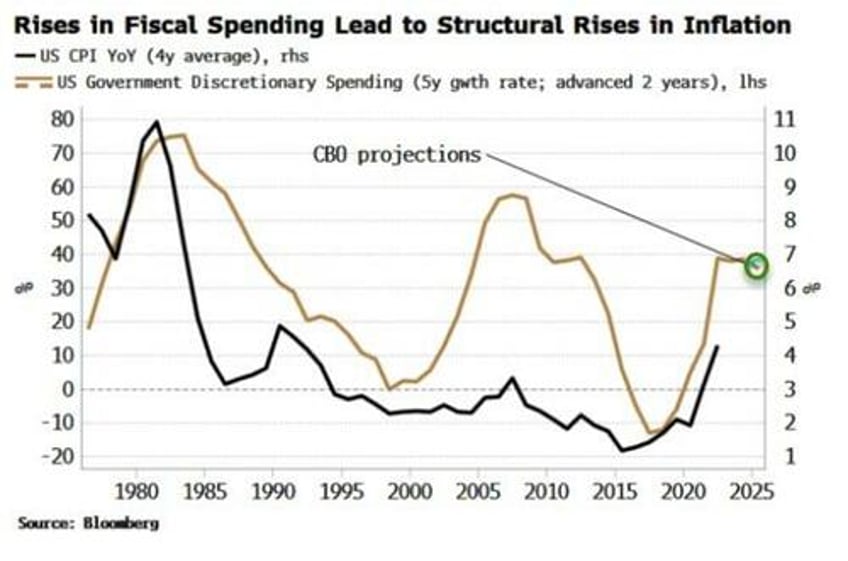

The Treasury put is inflationary, with rises in pro-cyclical (discretionary) fiscal spending leading to structural increases in inflation.

Peter Bernholz, in his classic text, Monetary Regimes and Inflation, shows that every high- and hyper-inflation episode of the 20th century was preceded by substantial government expenditures funded by large central-bank balance sheets.

The US is not currently facing hyperinflation, but it should come as no surprise if inflation remains persistently elevated in this environment.

That perhaps explains the principal reason for Mr Stiglitz’s confidence that Team Transitory is right, and Team Persistent - as he christens the other side - is dead wrong: namely that he does not believe excessive fiscal spending caused the recent inflation.

Either way, if you find little utility, as an investor, in more academic debates, you can instead stick to practicalities.

As it becomes clear inflation is on its way back, bond yields and breakevens will rise, stocks will fall, with the highest-duration sectors such as tech facing the most downside, credit will worsen, and gold and other precious metals, as well as commodities, should rise.

Joining Team Profitable will prove the most satisfying choice.