authored by Aaron Gifford via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Around this time last year, Franklin Central School in upstate New York faced a $1.46 million budget gap and painful choices: Push for a double-digit tax increase, lay off teachers, or send high school students to a neighboring district.

The state was dealing with its own financial issues and reserved the right to shift state aid amounts based on demographics, regardless of the short notice. Franklin was ultimately held harmless, a legal term for being released from responsibility; its state aid remained at $4.6 million, or about 56 percent of the district’s 2024 to 2025 budget.

With state aid flat, there was still a 4 percent tax hike, and $200,000 was applied from the district’s reserve fund. Some positions were eliminated through attrition, and Franklin partnered with neighboring districts to share staff in limited circumstances. But at least no jobs were lost, and the older kids weren’t sent away, Superintendent Bryan Ayres said.

The school building serves fewer than 200 K–12 students in a low-income rural area in New York state’s southern tier region west of the Catskill Mountains. It had three seniors in its class of 2023. The per-pupil expenditure rate is about $35,800, according to the district website.

“The hold harmless piece is critical for us,” Ayres told The Epoch Times, adding that community organizations use the school building for events on evenings and weekends. “The loss of a million dollars in state aid would cripple the community.”

Ayres said that during the pandemic, Franklin spent its federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds, more than $1 million, on equipment and services, not additional staff the district couldn’t pay after federal money went away.

Districts across the nation that used ESSER to bolster staff and hire teachers during the pandemic now face a fiscal cliff, but unlike Franklin, they won’t be held harmless for their circumstances or prior spending decisions. ESSER funding, which totaled $190 billion over three years, expired in September.

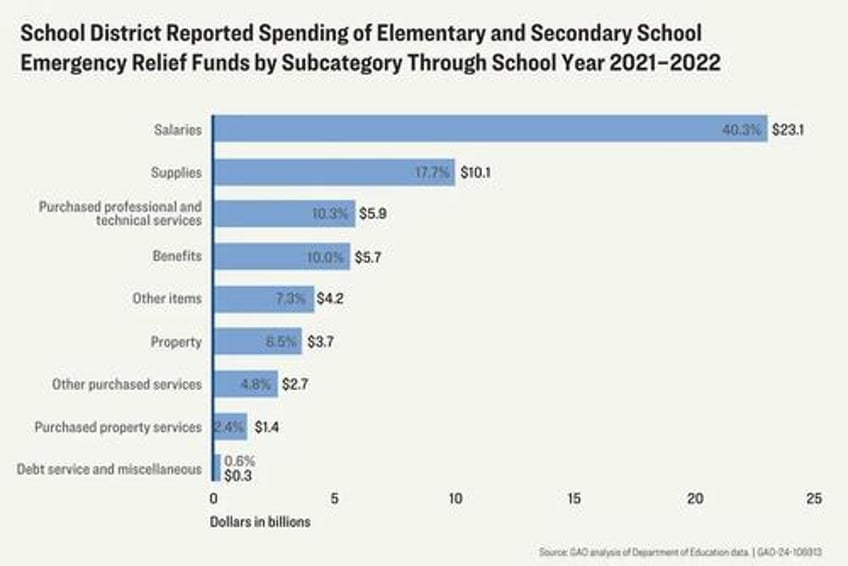

The U.S. Government Accountability Office reported on Oct. 23 that more than half of ESSER funds were spent on salaries and benefits.

It also said states provided oversight on spending: A New York state district’s request for a community center was denied, and in Florida, Texas, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, upgrades or renovations to athletic facilities were not funded. But in New York state and Texas, the report said, ESSER money was allowed to “replace lost state funding and maintain basic operations.”

Chad Aldeman, an education researcher, columnist, and former policy director of the Economics Lab at Georgetown University, said large urban districts with high poverty rates received the largest share of ESSER grants.

Aldeman estimated that 129,000 teaching positions could be cut by summer 2026. His calculations are based on the student–teacher ratios that decreased between the 2018 to 2019 and 2023 to 2024 academic years with the hiring of more teachers with ESSER funds. He completed a spreadsheet that lists staffing levels in thousands of districts. To return to pre-pandemic levels, it shows, for example, Miami-Dade in Florida would need to cut 794 positions; San Francisco 647; Omaha, Nebraska, 290; and Hempstead in Nassau County, New York, 62.

“This has happened before,” Aldeman told The Epoch Times. “During the Great Recession, schools shed 364,000 jobs. It was a big decline in the public sector.”

The Learning Policy Institute reported that during the 2023 to 2024 academic year, nearly 407,000 teaching positions remained vacant or were temporarily filled by uncertified adjuncts.

By contrast, Emerson Collective’s Work in Ed Page, which is updated weekly based on publicly available online postings, indicated that on Oct. 15, there were fewer than 45,000 available teaching positions, most of them requiring certifications, across 49 states and the District of Columbia. Emerson Collective is a policy organization that advocates the use of data analytics for addressing issues in education, public safety, and other areas.

Career transition services firm Challenger, Gray, and Christmas reported on Oct. 14 that there were 25,396 job cuts in the U.S. education sector in 2024 compared with 7,878 the year prior, an increase of 222 percent. Those figures include all job types in K–12 education, colleges and universities, and vendors that provide support services to learning institutions.

An April white paper by the American Institute for Research and the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research indicated that in Washington state, about 25 percent of the money provided to districts funded new employees, and most of the hiring took place in larger, more urban districts that received larger shares of ESSER funding and served high populations of minority students.

All told, Washington state school districts spent $497 million over three years on additional teachers and other employees.

“If districts are unable to manage reductions via attrition, it is likely that the end of ESSER fundings will be followed by significant layoffs,” wrote one of the paper’s authors, Dan Goldhaber.

Many large school districts, including in Houston; San Diego; Anaheim, California; Hartford, Connecticut; Seattle; and Cleveland, grappled with deficits and job cuts at the end of the prior academic year.

In Michigan, public schools would need to cut 5,100 teaching positions to return to pre-pandemic staffing levels and avoid growing budget deficits, according to an April report from the Citizens Research Council of Michigan. K–12 districts in that state collectively received $3.7 billion in ESSER funds. Based on declining enrollment and the lowest student–teacher ratios, the report notes that Detroit and Ann Arbor are among the 10 districts at the most significant risk for teacher layoffs.

“We don’t know exactly when each of Michigan’s 800-plus local school districts will face these tough staffing decisions or how deep the personnel impacts will go,” the report states. “However, we are starting to see some examples play out as local boards and administrators grapple with the end of their federal relief aid and the realization that their schools are educating far fewer K–12 students than before the pandemic.”

The Epoch Times reached out to the American Federation of Teachers and the National Education Association teachers union but didn’t receive a response.

Because the pandemic was deemed a national emergency, ESSER funds were approved quickly with little oversight. It was assumed that school districts would use the money to provide remote learning, assure the safety of staff and students, and preserve school employment levels. The final phase of the program, ESSER III, stipulated that 20 percent of the funds must cover learning recovery efforts.

Ahead of this school year, the board of education for Memphis-Shelby County Schools (MSCS) in Tennessee cut 1,100 positions to save $68 million.

During the June 25 board meeting, MSCS Superintendent Marie Feagins said 300 of those positions were contingent on ESSER funds, while 551 other jobs were to be eliminated through attrition. Dozens of management-level employees in the central office were to be offered classroom positions at lower pay rates. Pink slips were issued to more than 200 members of the instructional staff, including teachers who had not yet completed their certifications, those who performed below expectations, and those who were assigned to monitor remote learners.

Read the rest here...