US inflation slowed in April, according to CPI data released Wednesday. Yet even though they had this softer inflation data in hand, Federal Reserve policymakers still pared back their rate cut expectations for the year. In the new dot plot published Wednesday, the median projection showed just one rate cut before the end of 2024. That compares with three cuts in the March dot plot.

What gives?

Is inflation data no longer the main driver of interest rate policy?

Despite appearances, nothing is further from the truth.

Inflation trends are still massively important for Fed policy - and for markets.

The apparent contradiction between softer inflation and more hawkish rate projections is explained by two things: timing and confidence.

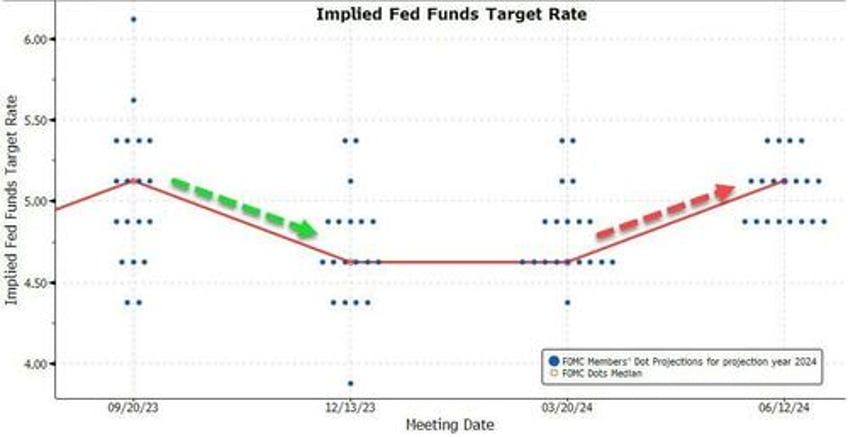

On timing, the reduced rate cut projections are a delayed response to the first quarter’s inflation scare.

When policymakers made their previous projections, on March 20, they only had two “hot” inflation prints in hand— January and February. These they largely brushed off as noise, or as Fed chair Jay Powell put it, “bumps in the road.” It was only when data for March was released on April 10 showing the third hot inflation print in a row that policymakers started to take seriously the possibility that inflation could be reaccelerating. Wednesday was the first opportunity since then for policymakers to revise their rate expectations for the year, and they took it.

Confidence, or a lack of it, explains why, despite two months of relatively benign inflation data in April and May, policymakers then didn’t go back to projecting three rate cuts this year.

The first quarter’s inflation scare effectively reset the clock. After three successive hot inflation prints, the Fed’s policymakers necessarily pushed back their prospective start date for rate cuts. Barring a crisis, that start date will remain pushed back, despite any subsequent softer prints.

The Fed will now need to see a string of benign inflation numbers before it regains the confidence that inflation is heading back to somewhere near its 2% target in a lasting fashion. This means that even if inflation continues to be benign, this year’s window for rate cuts is a lot smaller than it was in March. So, policymakers duly pared back their expectations for the number of rate cuts likely in 2024 (and had inflation continued to accelerate in the second quarter, we might even have got projections for rate hikes).

Allowing for these considerations of timing and confidence, there is no contradiction between May’s softer inflation and Wednesday’s more hawkish guidance from the Fed. Inflation remains the primary driver of rate decisions, not politics, nor government finances. This will remain the case at least until the end of Powell’s term in 2026. Although if Powell is then replaced by a political lackey, all bets will be off.

So, what will inflation do next?

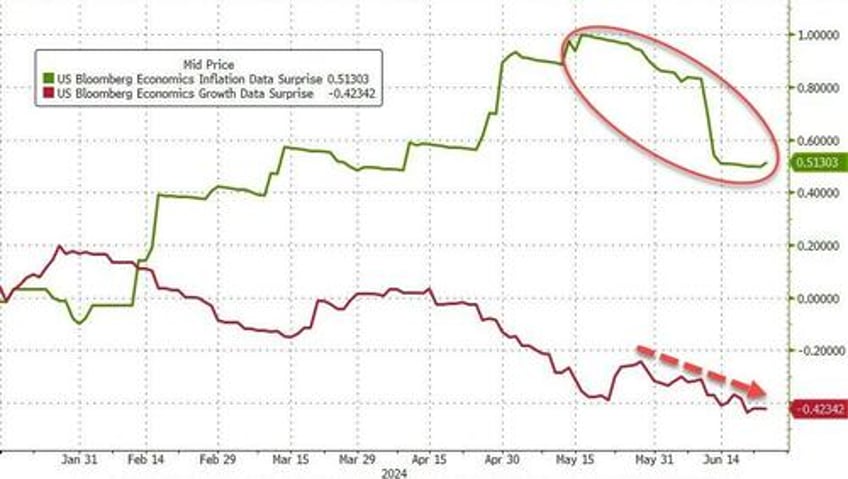

With money supply contracting, supply chain pressures benign, growth data mixed, and gasoline prices down, the base case is that inflation will continue to moderate.

If so, the Fed will likely be justified in cutting once or perhaps even twice before year-end.

But the risks to this outlook are substantial.

The wealth effect from rising asset prices could drive an upsurge in demand. Anatole has also highlighted the risk that housing rent, as measured by US inflation indexes, could moderate more slowly than many expect. On this note, Powell acknowledged this week that the lag between new rents and their impact on US inflation data may be longer than previously thought.

Valuations remain a concern both for bonds and for equities, with equity earnings yields very low compared to real yields on bonds, and even lower compared to real yields on bills. But with inflation moderating, hopes of rate cuts still alive, continued excitement over AI, and chunky share buybacks (thanks Apple), investors are currently inclined to ignore relative valuations and bid up the price of bonds and equities alike.