By Bas van Geffen, Senior Macro Strategist at Rabobank

US data further added to markets’ optimism that the Fed may be able to achieve a soft landing after all. Q4 GDP beat expectations by a wide margin. The 3.3% growth rate adds to the unexpected strength in the third quarter. Part of this upside surprise was driven by volatile components such as inventory building and net exports. Still, consumer expenditures accounted for the majority of growth in the final quarter of 2023, while business investment expanded at a moderate pace. While that’s again a recession delayed, we’re not convinced that it is cancelled. The GDP report paints a sharp contrast to survey-based data, which point to a cooling of the US economy.

But President Lagarde was the main mover of markets yesterday. The ECB kept rates on hold, as widely expected. However, against expectations, and contrary to the concerted effort by hawks and doves alike in the week prior to the meeting, President Lagarde gave much less pushback against market pricing. Markets interpreted this as distinctly dovish and yields dropped across the board.

The ECB president did indicate that the Council agreed it is too early to discuss rate cuts. The disinflationary process needs to advance further before the Council can be sure that inflation will hit their 2% target in a sustainable manner. That said, policymakers appear to have turned a bit more optimistic about the expected path of inflation. Lagarde summarized that the incoming data had largely confirmed the Governing Council’s previous assessment of the inflation outlook, and that the declining trend in underlying inflation had broadly continued. Domestic inflation is the key exception, though. ECB insiders suggested to Reuters that discussions could start in March, if the data suggest inflation is heading for 2% this year already. That’s quite the big caveat.

Over the past months, inflation has indeed turned out better than anticipated. But we’re not entirely convinced that underlying inflation is converging to target just as quickly as the ECB seems to expect. Domestic inflation, which Lagarde called the exception to the rule, underscores the risk that wage demands and profit margins could slow the disinflationary process.

The ECB acknowledges that the labour market remains tight, but sees the decline in the number of vacancies as a sign that the demand for labour is weakening. The Council expects this to gradually soften wage demands. Moreover, Lagarde sounded quite optimistic that firms are absorbing the higher wage costs by lowering their margins.

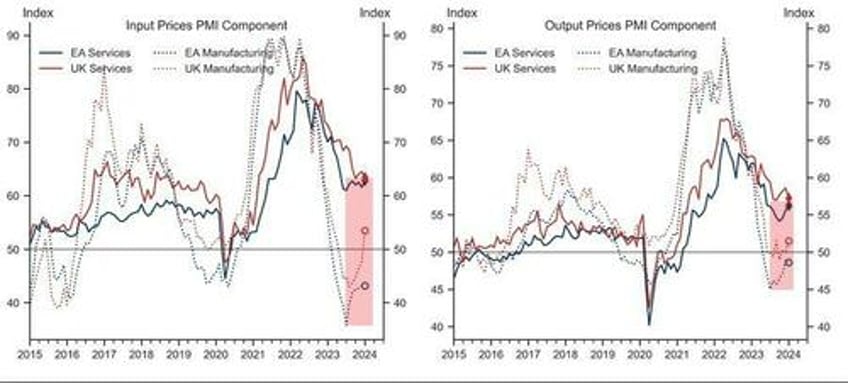

However, the PMI survey released earlier this week does not support that conclusion. The report noted that “service sector cost growth accelerated during the month, contributing to the steepest overall rise in prices charged for goods and services since last May.” Whilst the Eurozone-wide survey offered no further explanation for this rise in input costs, German respondents pointed to the influence of wage demands. Employers remain reluctant to layoff part of their workforce, particularly in the services sector. Employees are making good use of this to negotiate above-average pay increases. A similar dynamic is still the most plausible explanation for the rising input costs reported by employers in the services sector in other euro area countries.

Additionally, the increase in prices charged suggests that companies are still able to pass most of these costs on to the end user. That’s a red flag for two of the items on Lagarde’s disinflation ‘shopping list’: wage developments and profit margins.

Moreover, policymakers still expect a consumer-led recovery to begin in the course of 2024. High employment, wage increases and lower inflation should support disposable incomes and consumption. However, if that is the case, shouldn’t the ECB also expect the recent decline in vacancies to come to a halt? And doesn’t this mean that employees may have a structurally higher bargaining power than before, while the existence of demand allows companies to pass on part of these costs to the end user?

Given these risks, we had expected the ECB to remain more cautious. This caution is implicitly embedded in the ECB’s data-dependent approach. Yet, the lesser emphasis on the upside risks sticks out like a sore thumb, as evidenced by yesterday’s price action.

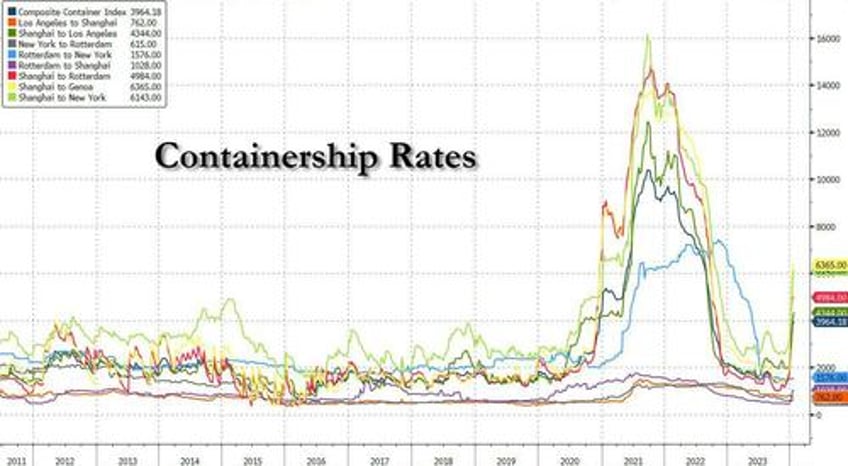

And those are just the domestic risks. Hamas and Israel haven’t yet been able to agree to the conditions of any ceasefire, and so the conflict in the Middle East continues. Houthi attacks have already led to a sharp increase in shipping costs since the turn of the year, particularly for routes between Asia and Europe. That makes it a particular risk for supply chains and prices on the European continent. That makes it all the more remarkable that Lagarde seemed to downplay the cost-push risk from developments in the Red Sea.

Reuters reported that China is now pressing Iran to tell the Houthis to rein in their attacks. Until now, China had remained on the side-lines of the conflict. The Houthis weren’t targeting Chinese vessels, and China probably doesn’t mind that they are keeping the US navy occupied. But, of course, not all Chinese exports are being transported on Chinese ships. So the attacks could still harm the country’s economic interests. Given the domestic issues that are still plaguing the Chinese economy, Beijing probably wants to avoid that external demand drops as well. And not just in the short term. Supply chain resilience has been a concern since the trade disruptions during the pandemic, leading to diversification away from China. Concerns about the relationship between China and the West are doing the same. A prolonged disruption of the Red Sea shipping route may only accelerate these processes.

Because domestically, things are still not looking too bright. Through last Monday the Hang Seng index had lost over 12% year to date. The index being at the lowest level in 19 years triggered government interventions. Beijing proposed to use cash in offshore accounts of state-owned enterprises to support the stock market – throwing good money after bad.

And the PBOC will cut the reserve requirement ratio. The reduction in banks’ required reserve holdings should, in theory, increase banks’ capacity to extend new loans. However, that does require demand for credit. And for these banks it requires that the expected returns outweigh the potential risks. Both are questionable at best, given the already high indebtedness of the various sectors of the Chinese economy.

The announced measures have stemmed the bleeding – for now. The Hang Seng index has recovered 6.6% since Monday. But it remains to be seen how durable this rebound is. Worse, the support measures came too late for many households. Many retail traders invested in callable contracts, rather than the underlying equities. The sharp decline in the index had already wiped out these structured notes. This week’s rebound only rubs salt in the wounds: retail traders that saw their contracts getting called have not benefitted from this week’s rebound. Bloomberg estimates that retail traders have lost roughly $1.6 billion. This does not bode too well for consumer confidence and consumer spending, which were already weak to begin with