The stock market is entering its topping phase. That’s not necessarily a reason, however, to hit the sell button as market tops typically persist long after fundamentals have ceased to support them, making them fraught with risks. The current market has yet to display the majority features present at previous tops, suggesting it can keep grinding higher — perhaps even culminating in a blow-off in prices — despite growing skepticism in the rally.

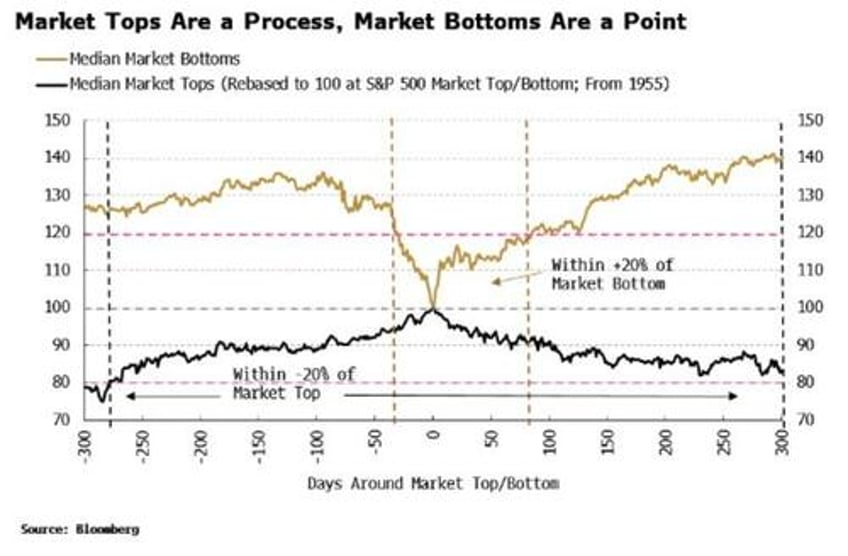

Markets exhibit asymmetric behavior at tops and bottoms. The latter are points in time, but tops are a process, often lasting many months. The most recent ones: the pandemic in 2021, the subprime crisis in 2007, the 2000 tech bubble and the savings and loan crisis in 1990 lasted many months – with the exception of the pandemic – and endured mounting disbelief before they finally gave way.

The stark difference between market tops and bottoms can be seen in the following chart. It shows the median bull market and the median bear market of the last 70 years. We can see clearly that market tops take many months to build, forming an inverted U-shape, and spending a significant amount of time within 20% of their peak price.

Markets bottoms on the other hand are V-shaped and are much more sudden affairs. They sell off abruptly but also recover rapidly, and spend considerably less time within 20% of their low price.

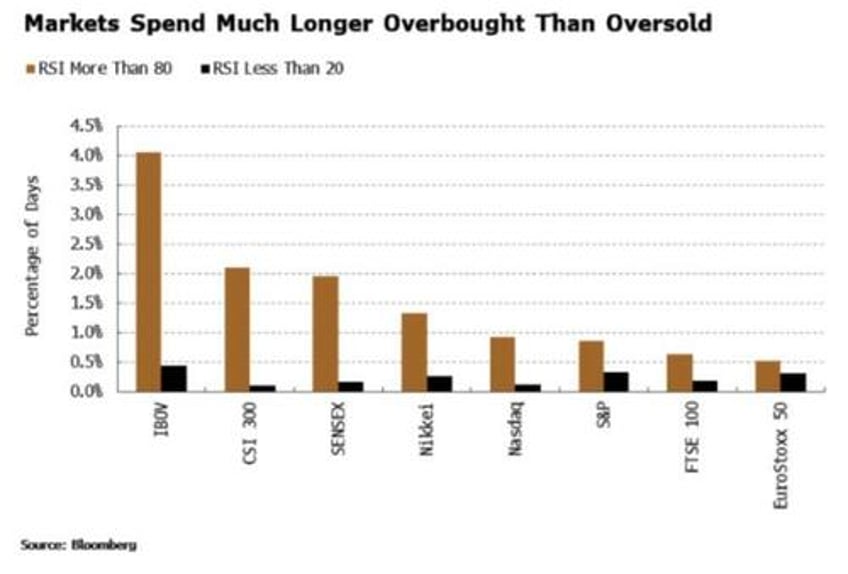

This is not just a US phenomenon. Stock markets globally spend more time being overbought than oversold. The percentage of days indexes spend with their 14-day RSI above 80 (an estimate of overboughtness) is much higher than the percentage of days when it is below 20 (for oversoldness) across global equity markets, with the effect more pronounced in EM, such as Brazil and China.

Market tops obey a variation of the Anna Karenina principle, in that every one is alike, but they all end in their own way. Each typically displays many of the following features at their climactic point:

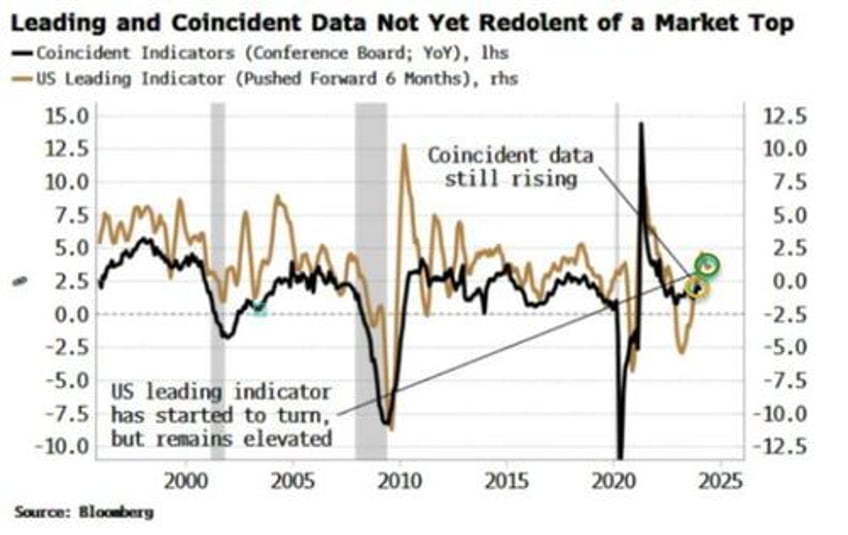

weakening leading economic indicators, with coincident indicators yet to decline

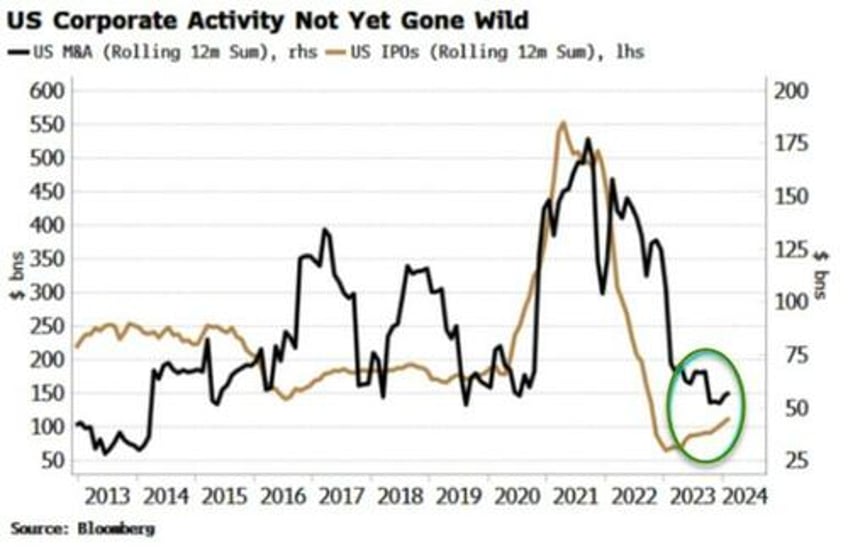

signs of over-extension in corporate activity

worsening excess liquidity

stretched breadth and price technicals

extreme bullish sentiment, and absence of bears

nosebleed valuations

Only some of the above are currently present, indicating the market is entering its topping phase, but one that could last several months yet.

Take economic data. The leading indicator for the US has started to turn down but from a high level, while coincident data is still increasing. Leading data, such as building permits and new orders-to-inventory ratios from PMIs, remain in a rising trend.

Credit markets and corporate actions typically display more signs of excess at market tops than is seen today. M&A, IPO and share buyback activity surge. Capex spending is rife, and more elaborate and questionable offerings are devised to take people’s money. We saw all of this at the last market top in 2021, as ultra-loose monetary policy and gallons of pandemic cash caused a wave of corporate activity and gave birth to Ponzi schemes, such as many SPACs.

Today, though, and for now capex is muted, SPACs are out of favor, while IPO and M&A activity is far below the excesses seen at the tail-end of the pandemic.

Still, every cycle has its own quirks, and in this one it remains to be seen to what extent private credit is hiding the skeletons in the closet.

When it comes to excess liquidity, it has yet to roll over (as discussed in recent columns), which will act as a tailwind for stock prices.

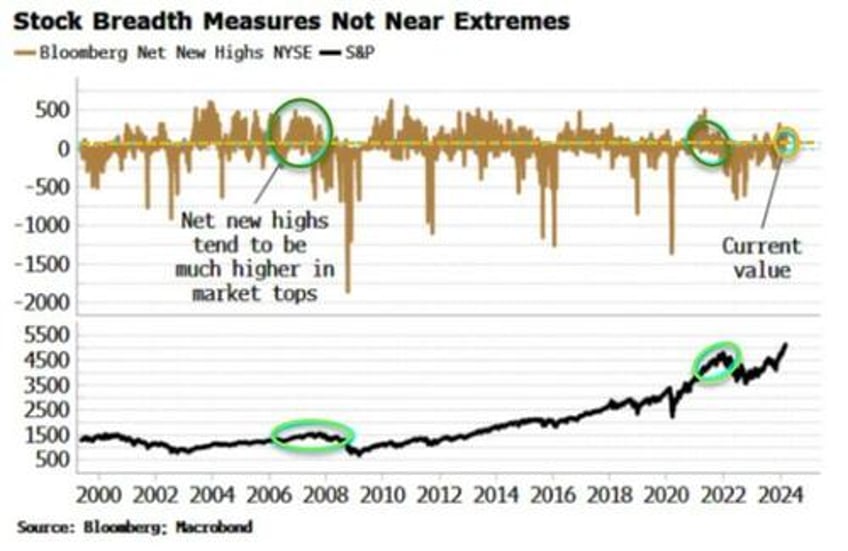

Furthermore, measures of market breadth, such as advance-decline lines, the percentage of stocks above their 200-day moving average, or the net number of stocks making new 52-week highs (shown in the chart below) are elevated, but not as extreme as the levels seen during prior market tops.

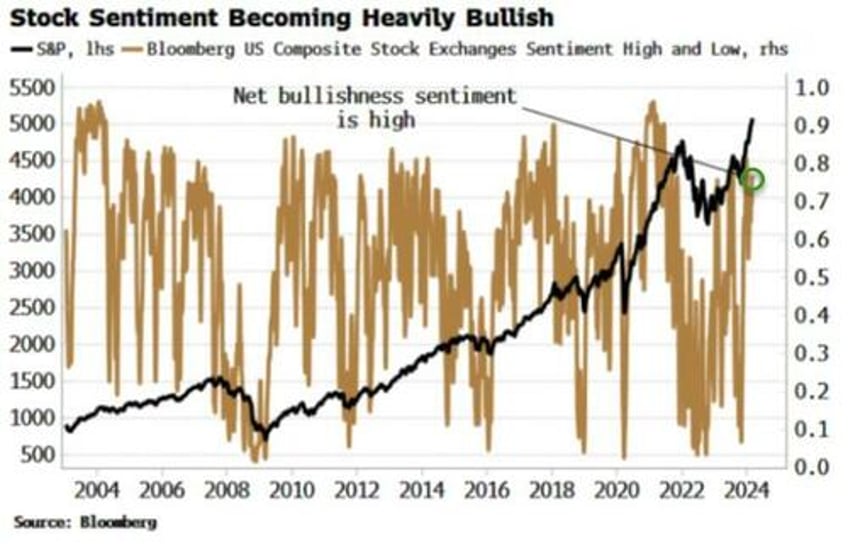

Sentiment is, however, reflective of a market in its topping phase. Bloomberg’s measure of individual stock sentiment is high (chart below), while the AAII’s (American Association of Individual Investors) net bullish indicator gauging retail-investor sentiment is not yet as stretched, but is still elevated. More glaringly though is AAII’s bear sentiment indicator, which is very low and suggests most stock bears have thrown in the towel, typical at market tops.

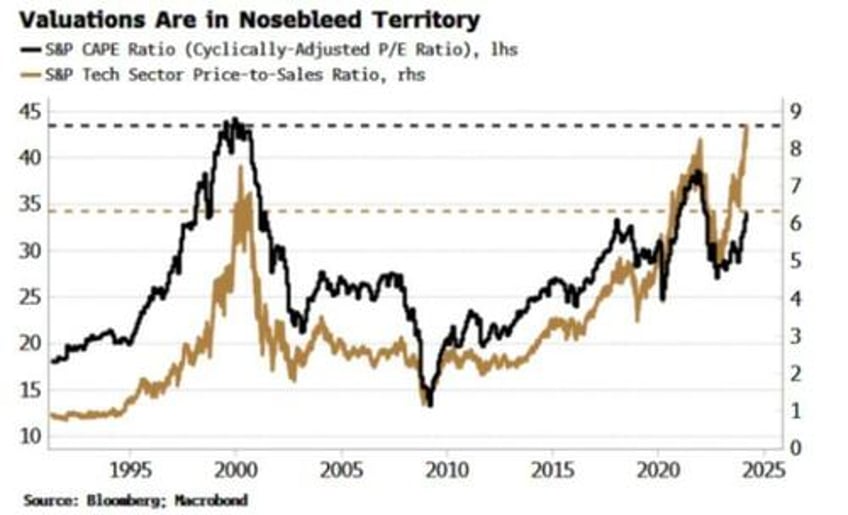

Also beginning to shout “topping market” is valuations. Multiples have been driving US returns, but even more egregiously in the tech sector. P/Es are driving tech returns more than they have at any time since the run-up to the tech bust in 2000 (outside of some very brief periods).

The S&P’s cyclically-adjusted P/E ratio is high, but still under its 2000 and 2022 peaks. However, the price-to-sales ratio is becoming faintly ludicrous, especially in the tech sector, where it’s at all-time highs at almost 9x, with some firms’ considerably more (Nvidia’s is at 36x …).

Valuations are of course execrable timing devices, but they are emblematic of how market tops can run and run long after any rational justification can be made for them doing so — other than that there’s a greater fool ready to take your position.

Previous tops have lingered well past their widely perceived sell-by date. The 2007 market kept going long after various subprime mortgage-bond prices had fallen, funding spreads had blown out, and hedge funds had shuttered, while in 2000 stocks continued their ascent despite growing evidence many companies were neither bringing in revenues nor making any profits.

It is unlikely this top will be much different, in the process creating much angst for bulls worried they’ll get out too early, while at the same time virtually eliminating bears, incandescent that the market is defying all sense and reality.

Market tops ultimately please no-one, which is why they outlast widespread disbelief. We’ll likely need to see more signs of a weaker economy, deteriorating liquidity, stretched technical indicators and corporate excess before the current top enters it endgame.