By Benjamin Picton, Senior Macro Strategist at Rabobank

Normal Service Resumed

UK CPI inflation shook off the narrative of the previous 24 hours by surprising on the low side yesterday. The headline number printed at -0.6 m/m, well below the -0.3% median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg while the core number also came in well below expectations. The falls were sufficient for year-on-year inflation to overcome unhelpful base effects to remain unchanged on both the core and headline reading.

Overnight Fedspeak also pushed markets back into dove-mode. Austan Goolsbee of the Chicago Fed was deployed to whisper calming sounds into the ears of rates traders after the upside surprise in January US CPI figures saw 2-year Treasury yields pump 18bps higher on Tuesday. Some of that move was unwound yesterday as 2-year yields fell by 8bps.

Goolsbee said all the right things to assure markets that rate cuts are still on the cards. Month-to-month deviations are no big deal, because “rate cuts should be tied to confidence in being on a path toward the target.” Traders shouldn’t fret about the January CPI figures, because “even if inflation comes in a bit higher for a few months, it would still be consistent with our path back to target.” And the coup de grace: the Fed’s inflation target is based on PCE, not CPI.

There are a few problems with this line of thinking. As we pointed out on Monday, the Fed might target PCE, but that hardly means that CPI is irrelevant. It is still an important measure of inflationary pressures in the economy, and is a good enough metric that most other major central banks use it as their preferred inflation gauge. Ignoring the signal from CPI would be a case of process-driven thinking triumphing over common sense, and invites the prospect of policy errors that could be embarrassing and costly to correct later on.

What’s more, is Goolsbee right that inflation being higher for a few months is still consistent with a return to target? Certainly not if you annualize the January CPI numbers. That would give a headline reading of 3.6% and a core reading of 4.9%. Granted, there are going to be differences between CPI and PCE, but numbers like that don’t scream “CUT RATES!” to me. With a March cut already off the table, the prospect of a cut in May very much hangs on inflation prints in the months ahead coming in materially lower than the numbers for January. We remain of the opinion that the Fed won’t be cutting rates until the June meeting.

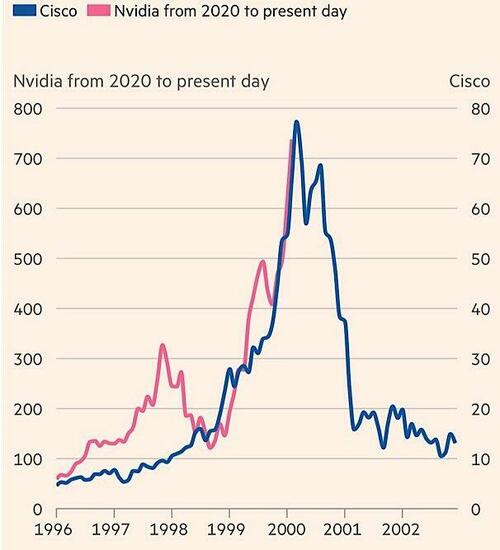

Nevertheless, Goolsbee succeeded in calming the markets enough for bond yields to fall and stock prices to resume their march into the stratosphere. We had a lot to say on Monday about equity valuations, and somebody called my attention to an interesting (if intentionally incendiary) graph doing the rounds on X from an article published in the FT last year. The comparisons between the recent price action in various AI darlings and some of the tech names of the late 1990s is interesting, and becomes even more interesting when comparing the multiples that those ‘90s-era stocks were trading on, and the total return investors who bought at high multiples would have received in the intervening period.

Remember, this was the period of Alan Greenspan’s ‘irrational exuberance’, but maybe something really has changed since? After all, Bill Clinton was running budget surpluses in the 1990s, the USA was the undisputed military and economic hegemon, and the status of the US Dollar as the global reserve currency was unquestioned. None of those conditions hold to the same extent any longer, although our Global Strategist Michael Every recently argued the case for the Dollar remaining monetary lingua franca for the foreseeable future (in a nutshell: there is no viable alternative).

Much will depend on the future path of inflation, because the kind of extreme money-earnings growth that justifies the multiple expansion that we are currently witnessing really only makes sense if you believe that the value of the currency is going to be eroded at a faster rate in the future than it was in the past. But this doesn’t gel with surveys of inflation expectations, the shape of the yield curve, or implied inflation expectations from the difference in yields between Treasury Bonds and TIPS.

So, somebody is going to have to be wrong. Is it going to be the equity market, or the bond market? Or is it me, and are we headed for a new nirvana of explosive AI-driven productivity that fulfils Irving Fisher’s infamous October 1929 prediction that “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau”?