By Stefan Koopman, Senior Macro Strategist at Rabobank

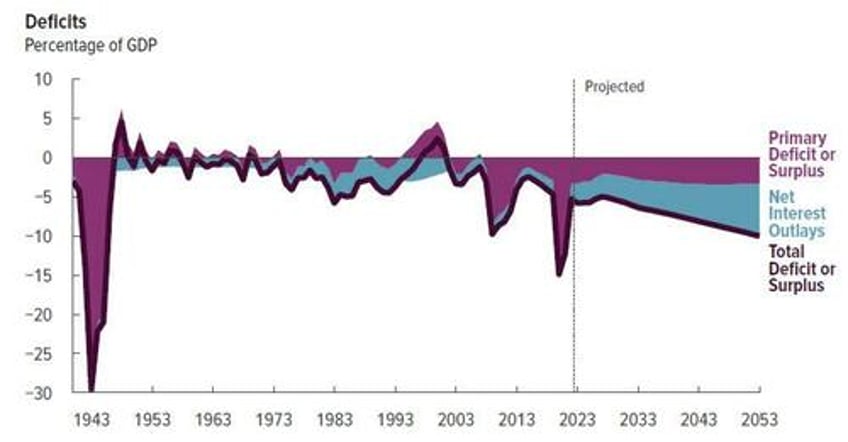

While most agree the US credit downgrade by Fitch will have limited real-world impact, it did serve as a reminder of the frankly unhinged state of US fiscal policy. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal deficit equals 5.8% of GDP in 2023, only declining to 5.0% of GDP by 2027 before growing steadily to reach 10.0% of GDP in 2053. The clear risk that a fiscal course correction has to be made someday caused equity investors to ‘swipe left’. The European Stoxx 600 closed down 1.6% - its largest drop in a month - and the S&P 500 slid 1.4% as well. The Nasdaq tumbled by 2.2%. The July rally had forced shorts to cover and brought in some reluctant recession-fearing buyers, leaving risky assets fragile.

The sell-off makes sense as an instinctive reaction, even if the downgrade does not change the practical value of US Treasuries. It is still a reserve asset that (eventually) pays you a coupon and hands back your notional, it has an investment proposition if you see yields falling, and it is very useful collateral. Give or take a few basis points, UST yields were essentially unchanged after the Fitch slap on the wrist. Indeed, bond investors only started to swipe left after the Treasury's quarterly refunding announcement of higher-than-expected issuance. 10-year USTs are now trading at 4.13% - some 15bps higher than earlier this week and a 2023 high. The dollar appreciated to 1.093 versus the euro reflecting yesterday’s broader risk off sentiment.

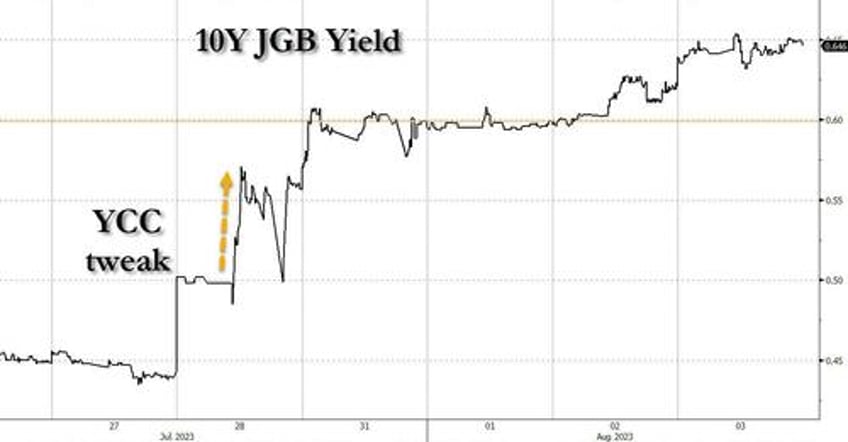

The Bank of Japan came into the market for the second time this week, sending a signal that its tolerance for higher bond yields has limits. It remains vague what exactly the Bank of Japan was attempting to signal by its change to YCC last week, but its actions make clear that it won’t tolerate a rapid move to the new 1% upper limit. The yen weakened a bit and now trades at 143.6 versus the dollar.

We explained yesterday why we tend to swipe left whenever the ADP survey shows up on our screens, but given that it was the only data release of the day and that it added to the bond sell-off, we’re going to give it the benefit of the doubt. The survey showed a higher-than-expected 324k rise in employment in July, well above the 200k consensus expectation for tomorrow’s official payroll figures. The job gains were boosted by an astonishing 201k rise in leisure and hospitality. This is also where we find the largest discrepancy between the latest couple of ADP and NFP reports, possibly due to differences in seasonal adjustment.

Now let's make a short segue into the world of regulation (… sorry, now please don’t swipe left on me!). The UK government's announcement to indefinitely extend the use of the EU's CE safety marking, instead of requiring businesses to adopt the UK-specific UKCA system, again swiping left on Brexit's core rationale. This seemingly mundane decision indicates continued alignment with EU standards, since CE compliance requires adhering to EU regulations. Even though UKCA isn’t abandoned, in practice it will mean that when a British firm only thinks about exporting something, it will seek to conform to EU standards and update these when the EU does.

The decision highlights three key implications.

The sudden rush to the exit and the absolutist interpretation of “sovereignty” have created real costs and real inefficiencies for UK businesses, which constrained their supply capacity and contributed to higher inflation.

Despite the "take back control" rhetoric, the UK finds itself forced to align with the EU in practical terms given their economic interdependence - a concept at the heart of Anu Bradford’s "Brussels Effect" theory. This was a live test of that theory, and the government has now recognized that pure sovereignty provides less control than having a seat at the table.

It casts doubt on the UK's planned regulatory controls on EU agri-food imports. This is a can that reportedly will be kicked down the road once again. High food inflation and a lack of political benefit of making the life of voters even more difficult are two key reasons. Even when controls are introduced at some point in the (distant?) future, limited infrastructure and lack of political will to invest in staff, scanners and structures suggest minimal real enforcement.