By Elwin de Groot, Head of Macro Strategy at Rabobank

No urgency, no rush

Although global disinflation has made considerable progress and should provide a window for interest rates cuts in the course of this year, central banks are in no hurry to cut. That, in a nutshell, was the key message this week from a slew of central bank comments, FOMC meeting minutes and ECB policy accounts. And it was broadly supported by the economic data as well.

This has seen markets pare and shift back their rate cut expectations further, continuing the trend seen since the end of last year. For the first time since 25 October 2023 are market participants now truly pricing the first (full 25bp) ECB rate cut in June 2024 rather than April or even March. Late December last year they were pricing a full three cuts by June! For the US/Fed it is an even more significant move, as a 25bp cut for June is no longer fully priced; instead this moment has shifted to July. End-December 2023, markets priced almost 3.5 cuts. So we’ve come a long way, even though markets are still a bit too optimistic in our view.

As our Fed watcher Philip Marey remarked earlier this week in his “Not So Fast” comment on the January meeting minutes, most participants at that meeting warned against the risks of moving too quickly to ease the stance of monetary policy. Some even noted the risk that progress toward price stability could stall. He therefore concludes that if progress on inflation were to stall indeed, we could see the Fed remaining on hold for longer. But his base case remains a start to the Fed cutting cycle in June, with modest steps of 25bps per quarter to reflect this risk of going too fast.

Three Fed officials (Cook, Jefferson and Waller) yesterday reinforced that message from the minutes, arguing that the direction in which inflation is heading is still positive but that the January blip warrants caution. As Waller said at a speech in Minneapolis. “Whatever word you pick, they all translate to one idea: What’s the rush?”

Turning to the ECB, this message is broadly the same. The 24-25 January meeting Policy Accounts showed that the Governing Council has been taking a bit of a ‘risk-based’ approach in its recent deliberations on policy. It felt it was too early to discuss any lowering of policy rates at the time: “The risk of cutting policy rates too early was still seen as outweighing that of cutting rates too late,” the Accounts note. “Having to reverse course, in the event that economic activity picked up more strongly than expected, wage growth accelerated or renewed inflationary pressures emerged, could entail high reputational costs.”

Although the Accounts argue that “[…] the new staff projections due in March were likely to show a downward revision to inflation for 2024”, it was seen as “prudent for the Governing Council to exercise caution on wage prospects and to await evidence that wage growth was actually moderating as projected for 2024. It was argued that the Governing Council would need to see some hard data confirming that wages had turned the corner”.

The negotiated wages data (slowing from 4.7% y/y in September to 4.5% y/y in December), released earlier this week, arguably don’t really fit that bill. Yes it slowed a bit, as also signalled by leading indicators such as from the Indeed survey, but at the same time we know that wage growth in the latter survey has been picking up a bit most recently. And we also know there is a sizeable gap between the trend in negotiated wages and overall compensation per employee, which may be affected by the continuing tightness of the labor market. And the same goes for (unit) labor costs, where the recent trend in productivity growth has showed no signs of recovery.

At the same time, the ECB still sounded fairly sanguine on the Red Sea issue with no particular mention of any potential inflation effects: “[…] the conflict in the Middle East had resulted in rising freight costs and a lengthening of delivery times owing to the recent attacks on freight ships in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. So far there had been no major disruption of trade and the main impact had come from ships taking longer routes around Africa, resulting in higher shipping rates and longer delivery times. However, this had, anecdotally, already led to some euro area companies halting production because of a lack of components. In this context of heightened global uncertainty, it was seen as puzzling that international energy price developments had remained overall very benign.”

Yet the fact that it mentioned this issue several times in the Accounts does suggest that it is a factor that is being taken into account in the balance of risks and thus, perhaps, also in its wait-and-see stance. We will show, in a forthcoming piece, that the Red Sea issue is potentially a material risk to the inflation outlook, but there are considerable lags involved, which makes it hard to assess. For now this may seem overshadowed by the falls in energy inflation (on the back of a plunge in wholesale gas prices) and the effects of thawing supply chains back in 2022-23.

Nevertheless, the overall ‘taste’ of the Accounts, with remarks such as “Inflation was heading towards the 2% target, possibly at a faster pace than previously expected”, suggests that a proper discussion on when to cut interest rates will be on the menu for the Governing Council’s next policy meeting. Such a discussion could still result in wait-and-see approach for the months ahead, as we expect, but it could undermine the “no rush” message if not communicated properly.

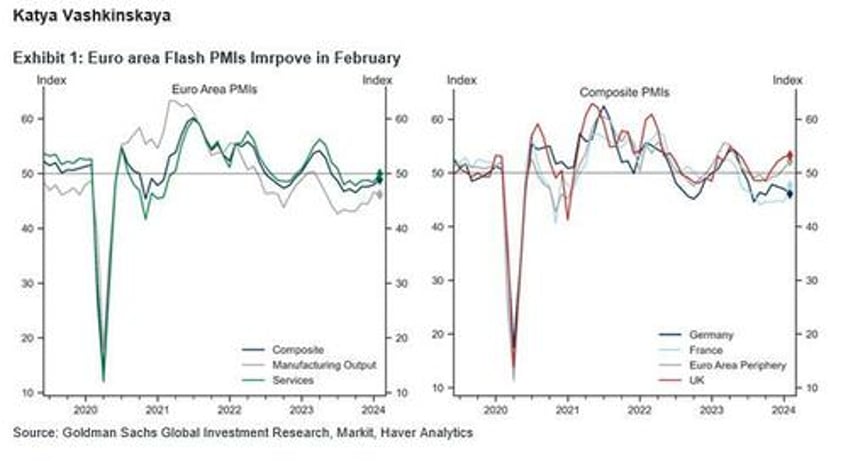

European data yesterday, arguably, supported a “no rush” stance. Although data for Germany disappointed with a significant fall back in its manufacturing PMI, this was offset by a sharp pickup in the French manufacturing survey.

The Eurozone aggregate for manufacturing still dropped as a result implying that the underlying assumption in the Eurozone preliminary estimate is a (modest) decline in the manufacturing PMIs for the Southern member states. For the services sector the message was similar: a fall in Germany but a rise in France. In this case, though, the Eurozone uptick of 1 point in the services sector index suggests that the Southern member states saw a modest rise. On balance, the HCOB Flash Eurozone Composite PMI Output Index rose from 47.9 in January to 48.9 in February. S&P Global noted that “Supplier delivery times had lengthened for the first time in 12 months in January, largely due to Red Sea related shipping disruptions, but faster lead-times were reported in February in a welcome sign of fewer shipping delays.” Still, the report also showed that selling price inflation accelerated, up for a fourth month running in February to hit the highest since last May, driven by the services sector (and, thus, wages).

In other words, the Eurozone economy may be finding a ‘bottom’ here as price pressures in the production chain could be starting to build again. That – in our view – would warrant a ‘risk based approach’ on the part of the ECB.