A re-acceleration in inflation is the primary endogenous risk for the stock market.

Stein’s Law states that:

“If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

What might stop equities in their tracks? The most compelling candidate – and therefore the one which investors should be most vigilant for – is inflation.

That, superficially, might be no great surprise in an environment where inflation has leaped to heights not seen in decades. But when we dig into it, we can see just how influential the fall in price growth has been for the rally, and therefore the acute risk a re-acceleration would pose.

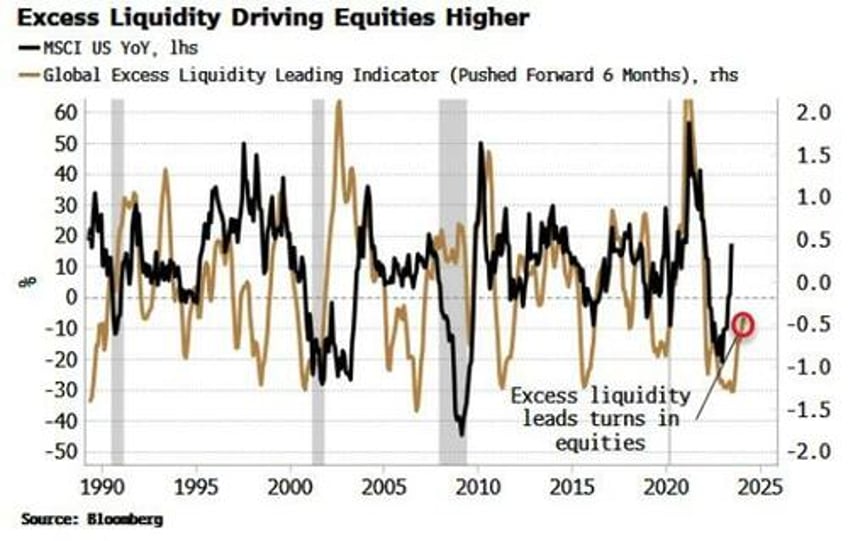

As the Federal Reserve removed monetary accommodation, liquidity conditions have nominally tightened. Yet excess liquidity – the difference between real money growth and economic growth – has been notably rising since March, providing equities with the strong tailwind they have enjoyed for most of this year.

Rising money growth turning up from very depressed levels and economic growth that has been falling have both supported excess liquidity. But much more important has been the influence of slowing inflation.

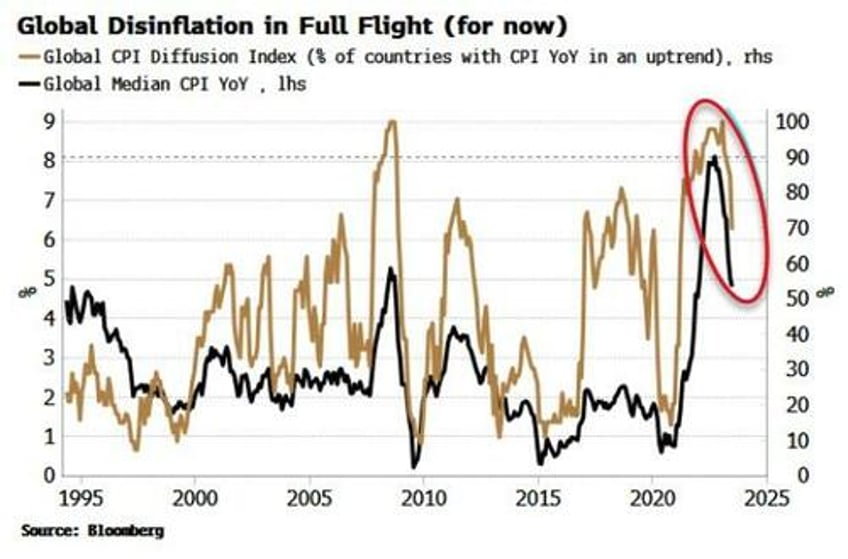

Inflation around the world has been easing, freeing up liquidity able to support risk assets. The flip side is that a volte-face in inflation would, all other things equal, mechanically lead to a fall in excess liquidity.

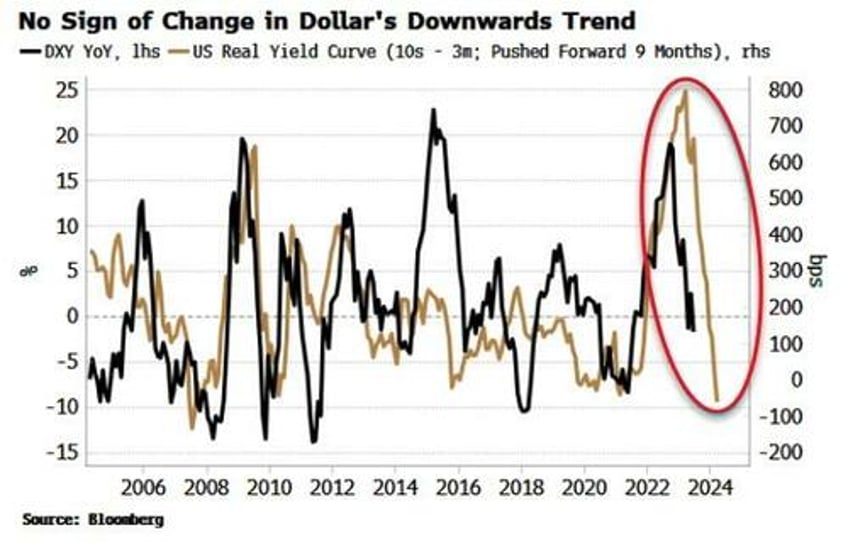

It’s not just inflation, though; the decline in the dollar has been very supportive of excess liquidity. Money growth for each currency in excess liquidity is measured in dollars, meaning that as it weakens, money growth in dollar terms rises. When foreign currencies are stronger, dollar-denominated assets are cheaper.

The dollar is in a strong down trend at the moment.

The real yield curve is one of the best (and one of the very few) indicators that actually leads the ups and downs of the dollar. It foreshadowed the peak of the dollar in September last year, and remains in a strong flattening trend now.

At the margin, the dollar is driven by the real return for a foreign buyer of US assets. The extreme flattening of the US real yield curve means that the real cost of borrowing dollars now exceeds the real return on longer-term US bonds, reducing demand for the US currency.

And here inflation rears its head again. The flattening in the real yield curve is now primarily being driven by the fall in US CPI, causing short-term real yields to rise faster than their long-term counterparts. A re-acceleration in inflation would reverse this, and signal the dollar is prone to strengthening, fanning a formidable headwind for excess liquidity.

In fact, a stronger dollar would be the cause of another headache for equities through the vector of earnings. EPS growth has been steadily declining, but the +13% drop seen in the dollar since its high last year soon promises to re-animate earnings; on the other hand, a stronger dollar would eventually depress them further.

We are in the thick of a disinflationary trend now, but my base case is inflation boomerangs higher late this year, or in the early part of next year.

Firstly, labor capacity remains very tight.

Secondly, elevated profit margins show increasing signs of remaining sticky (which, given the dynamics, is likely to continue fueling year-on-year effects).

And thirdly, China.

A worsening economic backdrop only increases the risk that easing there becomes less restrained. The bulk of the fall in global inflation has been driven by weakness in China, but easing will at some point break through, causing inflation to begin rising again.

Any inflation renaissance promises to be more troublesome than the debut. The vox populii is that inflation will go down and stay down. Not only would a re-acceleration in inflation pose a risk to assets from a re-pricing of Fed rate-hike expectations, but it would likely catalyze a significant reappraisal of asset pricing so as to incorporate inflation that has become embedded.

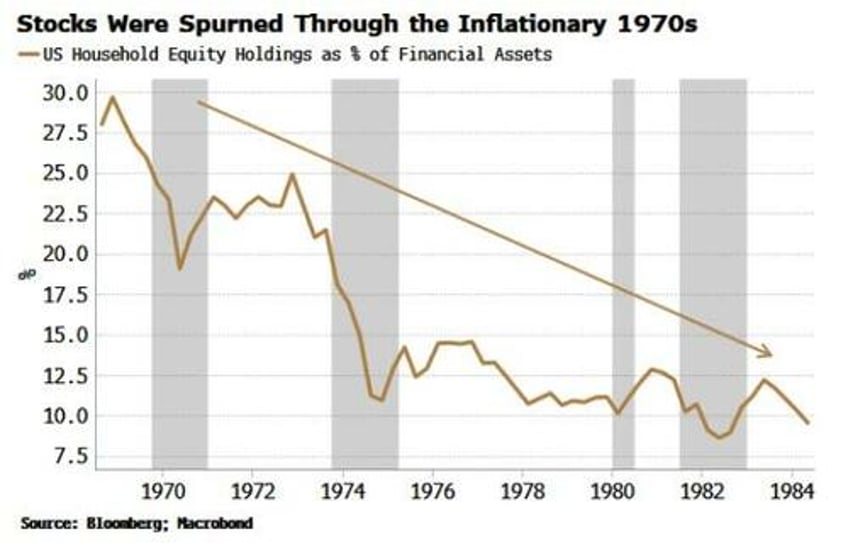

Term premium, which has remained remarkably becalmed in this inflationary episode, would likely rise, as bond holders demand higher compensation for lending money. But equities cannot adjust so easily.

The return on equity is essentially what corporations in the aggregate offer, and not all companies can adapt such that their bottom line remains steady when inflation is elevated. Thus bonds, which periodically offer an opportunity to renegotiate the coupon, begin to look more attractive. This is what we saw in the 1970s, with equity allocations falling all through the decade, while bond allocations rose. Stocks face the same repudiation in the current cycle.

Enjoy the party while it lasts (although inflation-hedged portfolios are a more prudent option). But when the specter of price growth returns, the sweet spot equities currently find themselves in promises to turn more bitter.