I received an email this past week concerning George Soros’ “Theory Of Reflexivity.”

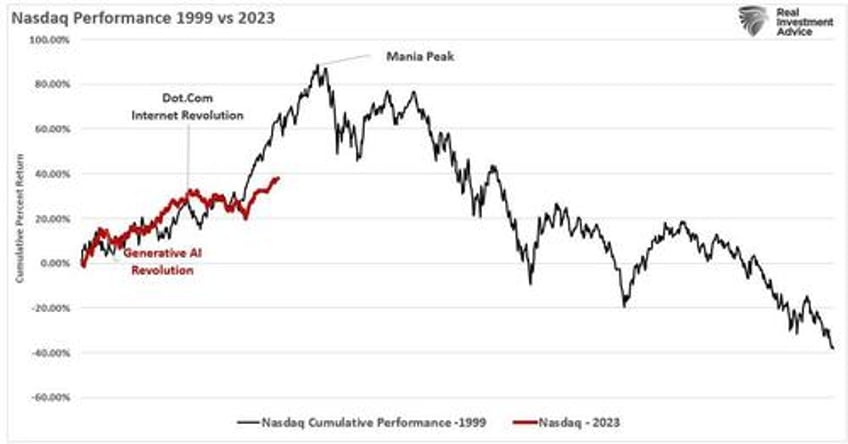

“I am not a fan of Soros, but this market has the look and feel of the dot com bust of 2000. In a few short words, the AI investment phenomenon is feeding on itself just as the internet and fiber did in 1999.”

It’s an interesting question, and I have previously written about the “Theory of Reflexivity.” Notably, this theory begins to resurface whenever markets become exuberant. However, concerning the email, there seems to be a similarity between the current “A.I.” driven speculation and what was seen in the late 90s.

There is, of course, a significant difference between the companies surging higher today versus those in the late 90s. That difference is that those companies involved in the “A.I.” race have revenues and earnings versus many Dot.com darlings that didn’t. Nonetheless, the valuations paid for many companies today, in terms of price-to-sales, are certainly not justifiable. The table below shows all the companies in the S&P 500 index with a price-to-sales ratio above 10x. Do you recognize any you own?

I picked 10x price-to-sales because of what Scott McNeely, then CEO of Sun Microsystems, said in a circa 1999 interview.

“At 10 times revenues, to give you a 10-year payback, I have to pay you 100% of revenues for 10 straight years in dividends. That assumes I can get that by my shareholders. It assumes I have zero cost of goods sold, which is very hard for a computer company. That assumes zero expenses, which is really hard with 39,000 employees. That assumes I pay no taxes, which is very hard. And that assumes you pay no taxes on your dividends, which is kind of illegal. And that assumes with zero R&D for the next 10 years, I can maintain the current revenue run rate. Now, having done that, would any of you like to buy my stock at $64? Do you realize how ridiculous those basic assumptions are?”

This is an important point. At a Price-to-Sales ratio of TWO (2), a company needs to grow sales by roughly 20% annually. That growth rate will only maintain a normalized price appreciation required to maintain that ratio. At 10x sales, the sales growth rate needed to maintain that valuation is astronomical.

While 41 companies in the S&P 500 are trading above 10x price-to-sales, 131 companies (26% of the S&P) trade above 5x sales and must grow sales by more than 100% yearly to maintain that valuation. The problem is that some companies, like Apple (AAPL), have declining revenue growth rates.

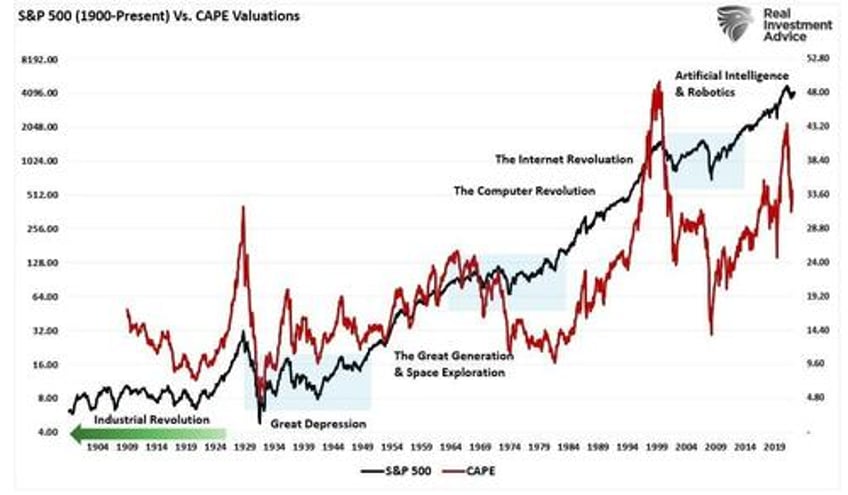

While it is believed that “A.I.” is a game changer, this is not the first time we have seen such a “revolution” in the markets.

As shown, there is an end to these cycles, as valuations ultimately matter.

So, what does this have to do with the “Theory of Reflexivity.”

The “Theory Of Reflexivity” – A Rudimentary Theory Of Bubbles

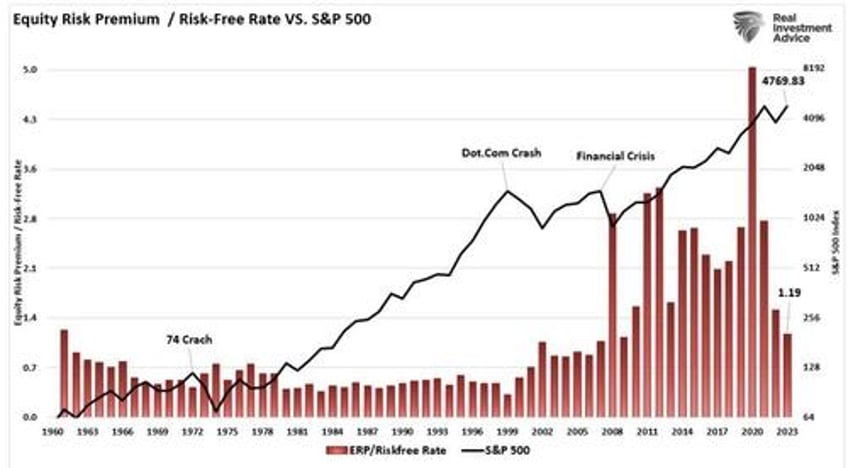

For investors, in the “heat of the moment,” silly notions like “valuations,” “equity risk premiums,” and “revenue growth” matter very little. Such is because, in the very short term, all that matters is momentum. However, over extended periods, valuations are a direct determinant of returns.

Despite one selloff after another leading to increased volatility, the markets are currently hitting all-time highs as the speculative chase for return heats up. However, the current market mentality reminds me much of what Alan Greenspan said about this behavior.

Thus, this vast increase in the market value of asset claims is, in part, the indirect result of investors accepting lower compensation for risk. Market participants too often view such an increase in market value as structural and permanent. To some extent, those higher values may be reflecting the increased flexibility and resilience of our economy. But what they perceive as newly abundant liquidity can readily disappear. Any onset of increased investor caution elevates risk premiums and, as a consequence, lowers asset values and promotes the liquidation of the debt that supported higher asset prices. This is the reason that history has not dealt kindly with the aftermath of protracted periods of low-risk premiums.

Alan Greenspan, August 25th, 2005.

A decline in perceived risk is often self-reinforcing in that it encourages presumptions of prolonged stability and thus a willingness to reach over an ever-more extended time period. But, because people are inherently risk averse, risk premiums cannot decline indefinitely. Whatever the reason for narrowing credit spreads, and they differ from episode to episode, history caution’s that extended periods of low concern about credit risk have invariably been followed by reversal, with an attendant fall in the prices of risky assets. Such developments apparently reflect not only market dynamics but also the all-too-evident alternating and infectious bouts of human euphoria and distress and the instability they engender.

Alan Greenspan, September 27th, 2005.

Once again, investors accept a low equity risk premium for market exposure. (Data courtesy of Aswath Damodaran, Stern University)

Such brings us to George Soros’ “Theory Of Reflexivity.”

“First, financial markets, far from accurately reflecting all the available knowledge, always provide a distorted view of reality. The degree of distortion may vary from time to time. Sometimes it’s quite insignificant, at other times, it is quite pronounced. When there is a significant divergence between market prices and the underlying reality, there is a lack of equilibrium conditions.

I have developed a rudimentary theory of bubbles along these lines. Every bubble has two components: an underlying trend that prevails in reality and a misconception relating to that trend. When a positive feedback develops between the trend and the misconception, a boom-bust process is set in motion. The process is liable to be tested by negative feedback along the way, and if it is strong enough to survive these tests, both the trend and the misconception will be reinforced. Eventually, market expectations become so far removed from reality that people are forced to recognize that a misconception is involved. A twilight period ensues during which doubts grow and more and more people lose faith, but the prevailing trend is sustained by inertia. As Chuck Prince, former head of Citigroup, said, ‘As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We are still dancing.’ Eventually, a tipping point is reached when the trend is reversed; it then becomes self-reinforcing in the opposite direction.

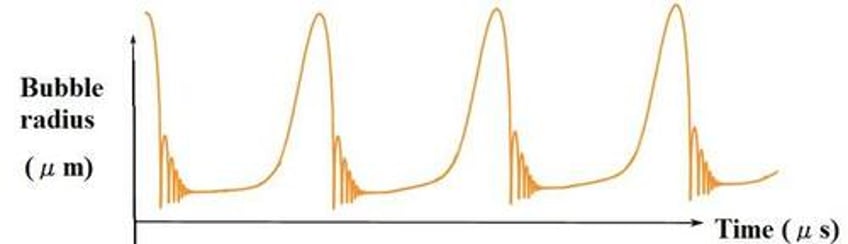

Typically bubbles have an asymmetric shape. The boom is long and slow to start. It accelerates gradually until it flattens out again during the twilight period. The bust is short and steep because it involves the forced liquidation of unsound positions.”

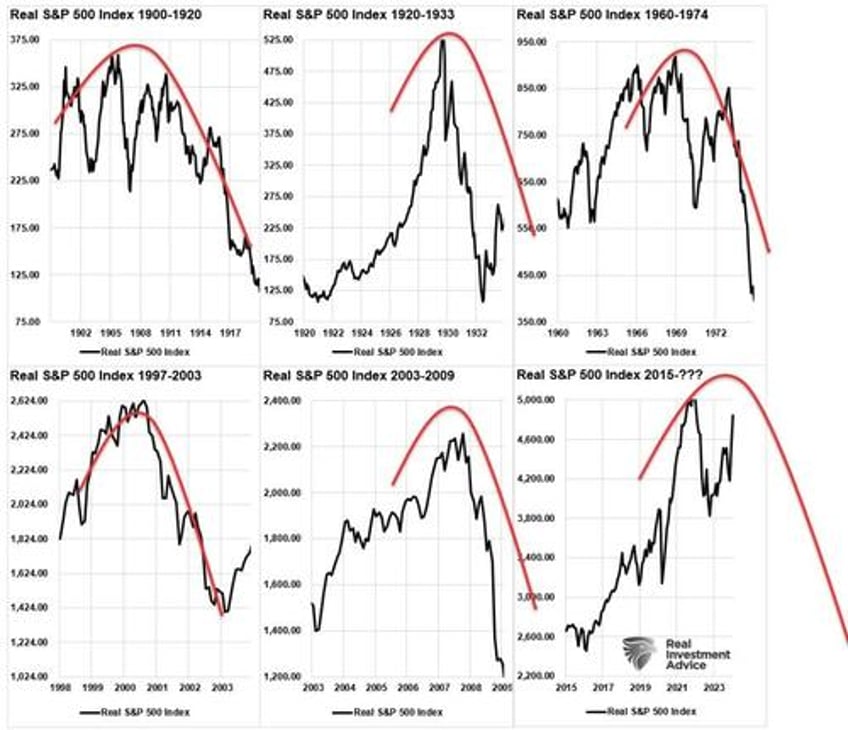

The chart below is an example of asymmetric bubbles.

Soros’ view on the pattern of bubbles is interesting because it changes the argument from a fundamental to a technical view. Let me explain.

Bubbles And Exuberance

Prices reflect the psychology of the market, which can create a feedback loop between the markets and fundamentals. As Soros stated:

“Financial markets do not play a purely passive role; they can also affect the so-called fundamentals they are supposed to reflect. These two functions, that financial markets perform, work in opposite directions. In the passive or cognitive function, the fundamentals are supposed to determine market prices. In the active or manipulative function market, prices find ways of influencing the fundamentals. When both functions operate at the same time, they interfere with each other. The supposedly independent variable of one function is the dependent variable of the other, so that neither function has a truly independent variable. As a result, neither market prices nor the underlying reality is fully determined. Both suffer from an element of uncertainty that cannot be quantified.”

The chart below utilizes Dr. Robert Shiller’s stock market data going back to 1900 on an inflation-adjusted basis. I then looked at the markets before each significant market correction and overlaid the asymmetrical bubble shape, as discussed by George Soros.

Of course, what each of those previous periods had in common were three things:

High valuation levels (chart 1)

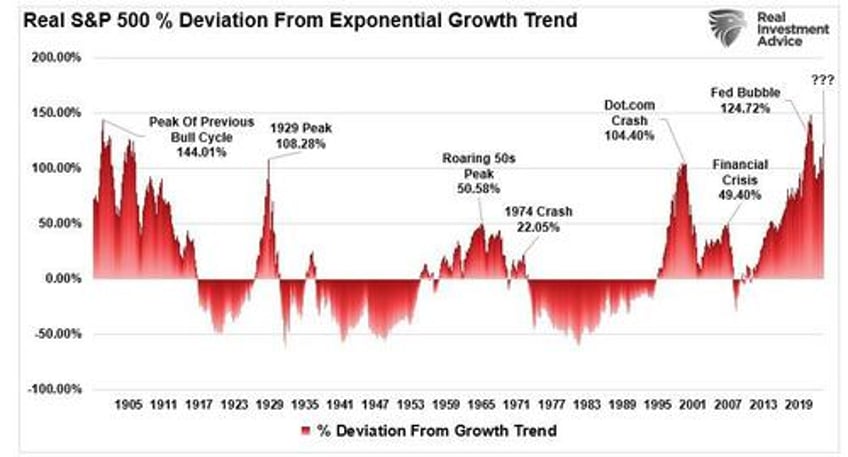

Large deviations from the long-term exponential growth trend of the market. (chart 2)

High levels of investor exuberance which drive chart 1 and 2.

The S&P 500 trades in the upper 90% of its historical valuation levels.

However, since stock market “bubbles” reflect speculation, greed, and emotional biases, valuations only reflect those emotions. As such, price becomes more reflective of psychology. From a “price perspective,” the level of “greed” is on full display as the S&P 500 trades at one of the most significant deviations on record from its long-term exponential trend. (Such is hard to reconcile, given a 35% correction in March 2020 and a 20% decline in 2022.)

Historically, all market crashes have resulted from things unrelated to valuation levels. Issues such as liquidity, government actions, monetary policy mistakes, recessions, or inflationary spikes are the culprits that trigger the “reversion in sentiment.”

Notably, the “bubbles” and “busts” are never the same.

Comparing the current market to any previous period is rather pointless. Is the current market like 1995, 1999, or 2007? No. Valuations, economics, drivers, etc., all differ from one cycle to the next.

Critically, the financial markets adapt to the cause of the previous “fatal crashes.” However, that adaptation won’t prevent the next one.

Conclusion

There is currently much debate about the health of financial markets. Can prices remain detached from the fundamentals long enough for the economic/earnings recession to catch up with prices?

Maybe. It has just never happened.

The speculative appetite for “yield,” fostered by the Fed’s ongoing interventions and suppressed interest rates, remains a powerful force in the short term. Furthermore, investors have now been successfully “trained” by the markets to “stay invested” for “fear of missing out.”

The speculative risks and excess leverage increase leave the markets vulnerable to a sizable correction. The only missing ingredient for such a correction is the catalyst that starts the “panic for the exit.”

It is all reminiscent of the 1929 market peak when Dr. Irving Fisher uttered his famous words: “Stocks have now reached a permanently high plateau.” The clamoring of voices proclaiming the bull market still has plenty of room to run tells the same story. History is replete with market crashes that occurred just as the mainstream belief made heretics out of anyone who dared to contradict the bullish bias.

When will Soros’ “Theory of Reflexivity” affect the market? No one knows with any certainty. But what we do know with certainty is that markets are affected by gravity. Eventually, for whatever reason, what goes up will come down.

Make sure to manage your portfolio risk accordingly.