This year’s hurricane season, which officially starts June 1, is being predicted by WeatherBELL as the “hurricane season from hell,” with weather patterns similar to those of 2005, 2017, and 2020.

Along with it, says the firm’s meteorologist and chief forecaster Joe Bastardi, will come the climate change blame game, which he calls a false narrative.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana, killing an estimated 1,833 people and causing approximately $161 billion in damages. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, Irma hit the Caribbean, and Maria hit the Caribbean and Puerto Rico, resulting in at least 3,364 fatalities and a combined cost of over $294 billion in damages.

In 2020, six major hurricanes landed, resulting in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) dubbing 2020 the “most active season in recorded history.”

Following each season, government officials, committees, and scientists were quick to blame climate change.

“There is perhaps no better example of the potential for devastating global warming impacts than the Gulf Coast and Hurricane Katrina,” the U.S. Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming stated after Katrina.

“While the contribution of human-caused warming to Hurricane Katrina is difficult to quantify, scientists have unearthed a trend towards larger, more intense storms as oceans around the world warm.”

After Irma, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres called the 2017 season “the most violent on record.”

“Changes to our climate are making extreme weather events more severe and frequent, pushing communities into a vicious cycle of shock and recovery,” he stated.

After the 2020 season, Jim Kossin, an atmospheric research scientist at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, blamed “warmer-than-average ocean temperatures” for the hurricane “hyper-activity.”

He said an increase in more ferocious hurricanes over the past 40 years was linked to climate change.

Mr. Bastardi said he expects to hear similar messaging this year if it pans out like he’s predicting.

“If you hang around people constantly spouting negative stuff and how bad it is, guess what you’re going to believe? … It’s a great strategy for pushing this thing—if I wanted to argue the CO2 [carbon dioxide] argument, I'd do exactly what they’re doing,” Mr. Bastardi told The Epoch Times.

“But there’s been no increase. And the size of the storms is getting smaller. That’s the other thing: hurricanes are smaller and more compact.”

Oceanographer and certified consulting meteorologist Bob Cohen concurred.

He said there’s currently a transition from El Niño patterns to La Niña, which is “correlated with higher-than-normal hurricane activity.”

“Right now, the subsurface temperatures are much cooler than during El Niño,” he told The Epoch Times. “The immediate near-surface temperatures are still warmer, but the subsurface water pool and the warm water pool have dissipated, and so once that pops to the surface, it becomes La Niña,” Mr. Cohen said.

He said he expects “we'll hear a lot more alarmist messaging” if 2024 is a busy hurricane season, as predicted.

But, like Mr. Bastardi, Mr. Cohen said hurricanes aren’t getting bigger or more intense. He said that as temperatures naturally warm coming out of the Little Ice Age, hurricanes and weather events will get less intense—not exponentially worse.

Basic Physics and Temperature

The Earth endeavors to exist in a state of equilibrium; it tries to equalize the temperature between the equator and the poles, which drives weather, according to Mr. Cohen.

“When you look at the 50,000-foot big picture, the Earth is a heat engine,” he said. “The tropics remain fairly constant in temperatures, and it’s the poles that have the greatest change.

“The gradient drives the storms. … If the poles warm, the temperature gradient decreases, which would mean less of a requirement for more intense storms from Mother Nature. It’s basic physics.”

Mr. Bastardi agreed.

“Look at Ida versus Betsy,” he said. “Betsy’s hurricane-force winds extended out 150 miles to the west and 250 miles east. Ida 50 miles to the west, and 75 miles to the east. They’re both category 4. They both had similar pressures. Which was the worst storm? The bigger storm. But they don’t tell you that.”

NOAA’s hurricane division shows Hurricane Betsy hitting Florida and Louisiana in 1965 with a central pressure of 946 millibars and a maximum wind speed of 132 miles per hour. Hurricane Ida hit Louisiana in 2021 with a central pressure of 931 mb and a maximum wind speed of 149 miles per hour.

However, NOAA data doesn’t include the overall size of a hurricane.

“Hurricanes now are like fists of furry rather than giant bulldozers that come in and plow the coast,” Mr. Bastardi said. “But [NOAA] won’t show the entire picture. Because if they did, people would say, ‘What the heck!’”

He said the reason hurricanes are more costly now is because of increased infrastructure along the coasts, not because of increased severity.

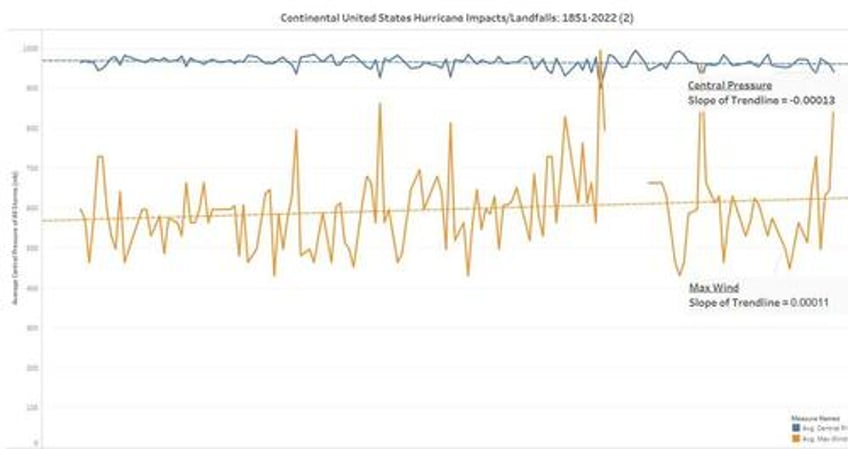

NOAA’s historical hurricane data dating back to 1851 supports the premise that hurricanes aren’t getting worse.

It adds as a caveat to its data that “because of the sparseness of towns and cities before 1900,” hurricanes may have been missed or their intensity underestimated.

NOAA’s data also shows hurricanes are getting less severe in terms of central pressure.

Even with possible missing data, the NOAA data show an average central pressure decline of 0.00013mb per year between 1851 and 2022 (2023 data isn’t included yet), and max wind had a marginal average increase of 0.00011mph per year for that same period.

The agency uses the Saffir-Simpson scale to categorize hurricanes from 1 to 5 based on maximum sustained wind speed.

Fear Before Reality

Government agencies, such as NOAA, often lead with an alarming statement about increased weather severity, but beyond the headlines, the data show a different story, Mr. Cohen said.

For example, in its 2023 State of the Science fact sheet titled “Atlantic Hurricanes and Climate Change,” NOAA asks the questions: “Has human-caused climate change had any detectable influence on hurricanes and their impacts?” and “What changes do we expect going forward with continued global warming?”

It answers itself by stating that “Several Atlantic hurricane activity metrics show pronounced increases since 1980.”

A few paragraphs later, NOAA states that if the data from the 1900s to the present is considered, “There has been no significant trend in annual numbers of U.S. landfalling tropical storms, hurricanes, or major hurricanes.”

Instead, there’s a “decreasing trend since 1900 in the propagation speed of tropical storms and hurricanes over the continental U.S.”

Mr. Cohen said NOAA’s approach is problematic. Its initial statements are “scary” and then “it discounts these same statements.”

“It’s very confusing because it goes back and forth between blaming climate change and blaming natural variability,” he said.

The reliance on climate modeling instead of observed reality is one of the problems with government reports, Mr. Cohen said.

Read the rest here...